My Regensburg Year Part 3: October 2024

It’s October in Regensburg and the weather is finally becoming seasonal. Long gone now are the heat waves of August and September; we have even turned on the heat a few times. For some reason, the colder weather does not deter Regensburg natives and tourists from sitting outside at the restaurants and cafés. Perhaps the opportunity to smoke while drinking is more important than bodily warmth.

The big event for us this month was our second visit from home, this time in the form of my daughters Sophie and Meghan, along with Meghan’s boyfriend Kevin. Sophie arrived first and we took her to Salzburg overnight and to Dachau. Once Meghan and Kevin arrived, we all took a trip to Weltenberg Monastery (pictured above) in nearby Kelheim. Access to the monastery is via a scenic boat ride or a 5 km hike. There is not a lot to see at the monastery—it has a Biergarten serving the monastery’s own brews, a church, and a chapel; the scenery en route is really the appeal. Before long, Meghan and Kevin journeyed on to Prague and Sophie headed home to Canada. We were left once again to ourselves, but the travelling continued with another trip to Weltenberg (this time with our neighbours Sam and Roxanne, and by foot rather than by boat) and to Landshut. We were really not optimistic about Landshut, having been stuck there for a while on our way back from Hallstatt in September. But once you get away from the train station and into the old town, it is really quite quaint. One surprise for us was happening upon the Chapel of Thecla, constructed in 1426 first as a chapel dedicated to Mary; its ceiling features a large eighteenth-century fresco of Thecla with elements from her apocryphal acts (contending with the lions and the townspeople of Antioch). We also found an interesting altarpiece dedicated to the life of Joseph in St. Martin’s Church; the images likely came from the artist’s imagination but they do have some overlapping themes from apocrypha texts (the boy Jesus in the carpenter’s shop from the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the death of Joseph from the History of Joseph the Carpenter).

Speaking of Thecla, one of my work tasks in the next month will be preparing a presentation for NASSCAL’s First Fridays workshop on Thecla traditions. The workshop organizer (Janet Spittler) planned on four presentations on Thecla for the Fall but one contributor pulled out. I was coerced into filling the slot and will use the time to get feedback on my chapter on the Acts of Paul for the Anchor Bible project.

I will present on another chapter from the book in early December for the Beyond Canon Project’s Scholars’ Brunch series. This year’s brunches started a few weeks ago with a paper from Roxanne Bélanger Sarrazin. To my dismay, there is no actual brunch served at these events but the participants are treated after the talk to lunch at a restaurant on campus. My presentation is entitled “And the Rest”: Apocryphal Tales of Disciples, Evangelists, and Other Saints.”

Among these “other saints” is the Virgin Mary, who is certainly too prominent a figure to be considered among “the rest” but apocrypha related to her dormition (falling asleep) is not widely known in scholarship, due largely from their omission from some of the more prominent apocrypha collections. Scholarship on these texts has been dominated by three scholars: Michel van Esbroeck, Simon Mimouni, and Stephen Shoemaker, with contributions of texts and translations by Victor Arras, Martin Jugie, Pilar González Casados, and Antonie Wenger. The number and variety of dormition traditions is enough to deter other scholars from diving into this material. And I can’t hope to include all of them in my chapter. Still, I needed to wrap my head around it all so that I could write something cogent about them.

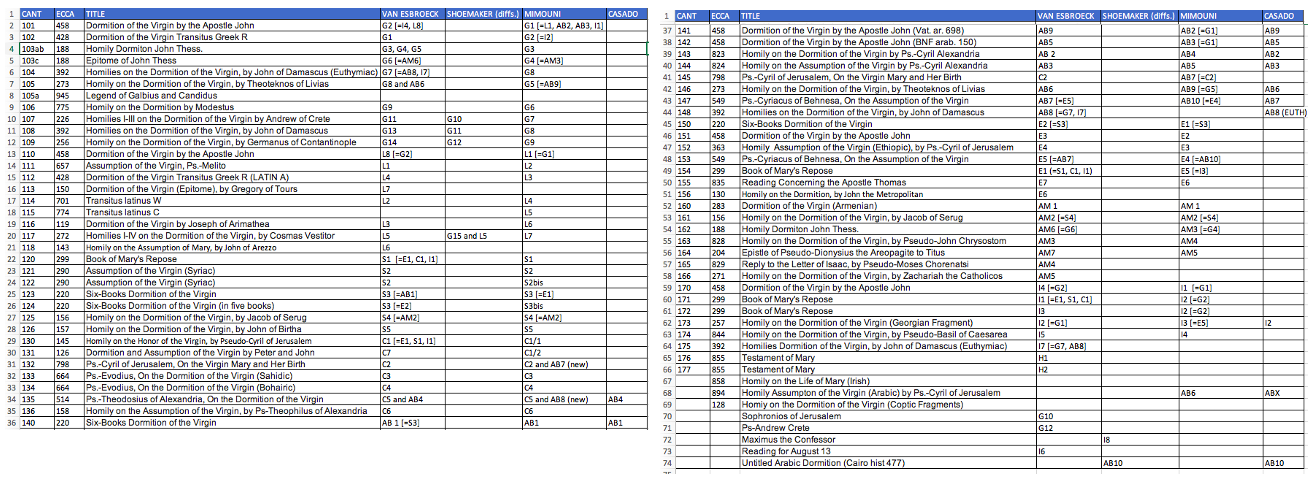

The number of texts differs depending on how one divides the material and decides what to include. Michel van Esbroeck was first to provide a list of the texts and started the tradition of separately cataloging each version (so that, for example, Ethiopic, Syriac, Coptic, and Georgian versions of a text are each given their own designations). His list encompasses 67 texts in nine languages (neglecting only the Church Slavic). Stephen Shoemaker largely follows van Esbroeck’s schema (with some omissions, additions, and adjustments), whereas Simon Mimouni provides his own arrangement of 55 texts. Mimouni’s method is largely reflected in CANT, which features 64 texts (numbered 101–177 with a few gaps between language groups). The biggest development since Mimouni’s work has been the publication of several Arabic versions in González Casado’s 2013 dissertation. While some of the designations assigned to the texts by previous scholars overlap, there is also considerable variation, leading to much confusion (not helped by the occasional error of identification). You can see below the results of my efforts to bring some order to this chaos (click to enlarge).

When preparing my entries on the dormition texts for e-Clavis, I tried to simplify matters somewhat by combining versions of the same text extant in multiple languages under one entry. But it is not as simple as it seems. How different does a version have to be before it should be considered a separate text? It is reasonable, I think, to combine the several texts of the so-called Palm tradition in one entry: the Ethiopic Book of Mary’s Repose (CANT 154, with parallel fragments in Syriac [120], Georgian [171, 172], and Coptic [130]; but keep separate the shortened Greek version (CANT 102; Transitus Greek R) paired with its Latin translation (CANT 112; Transitus Latin A) and Georgian fragments (CANT 172). So, for me, eight texts become two. To complicate matters further, e-Clavis has added eight texts not included on CANT.

Another way for me to find order is to distinguish between apocryphal narratives and derivative homilies, which I tend to give little attention in the book since they chiefly testify to the influence of earlier texts. Of all the dormition texts listed by CANT, 14 are of this type. Coptic homilies that feature embedded texts “found” by the homilist, however, are treated as narratives. In the end, I chose to focus in my chapter on the two main representatives of the Palm tradition (the Book of Mary’s Repose and the Assumption of the Virgin by Pseudo-Melito) and the earliest version of the Bethlehem tradition (the Syriac Six-Books Dormition, with some discussion of its popular Greek abbreviation the Dormition of the Virgin by the Apostle John). I also use the two versions (Sahidic and Bohairic) of the Homily on the Dormition of the Virgin by Pseudo-Evodius to describe the tendencies of the Coptic traditions.

Certainly there is more that I could (and wish I could) do, but I only have so much space! I will get to see what some of my colleagues think of my efforts next month.

References

Arras, Victor. De transitu Mariae apocrypha aethiopice. 2 vols. CSCO 342–343. Leuven: Sécretariat du CorpusSCO, 1973.

Esbroeck, Michel van. “Les textes litteraires sur l’Assomption avant le Xe siècle.” Pages 265–85 in Les actes apocryphes des apôtres. Edited by François Bovon. Publications de la faculte de theologie de l’Universite de Geneve 4. Geneva: Labor et Fides, 1981.

González Casado, Pilar, ed. “Las relaciones linguisticas entre el siriaco y el arabe en textos religiosos arabes cristianos.” Dissertation. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2013.

Jugie, Martin. La Mort et l’Assumption de la Sainte Vierge: Étude historico-doctrinale. Studi e Testi 114. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1944.

Mimouni, Simon. Dormition et assumption de Marie: Histoire des traditions anciennnes. Paris: Beauchesne, 1995.

Shoemaker, Stephen J. Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Wenger, Antoine. L’Assomption de la T.S. Vierge dans la tradition byzantine du VIe au Xe siècle. Études et documents. Archives de l’Orient chrétien 5. Paris: Institut français d’études byzantines, 1955.