Apostolic Lists as Sources for, and Transmitters of, Apocryphal Traditions about the Apostles

The following post is based on a presentation given at the 2023 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Society of Patristic Studies.

The exploits of the apostles are documented in a wide assortment of apocryphal acts composed between the second and sixth centuries, with expansions and transformations made in the centuries thereafter. A parallel stream of traditions is transmitted in a variety of lists of apostles and disciples that both inspired and were inspired by the apocryphal acts. Unfortunately, little scholarly attention has been paid to the lists—few have been translated into English, some have not yet been published, and with one exception, no survey of the material has appeared in apocrypha collections.

The urge to list apostles has its origins in the New Testament, with the call of the Twelve in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 3:13–19 par.; also Acts 1:13); but these are not just a list of names, even at this early stage there is additional information provided: nicknames (Peter, the sons of thunder), relationships (Peter and Andrew are siblings; as are the two sons of Zebedee; James is the son of Alphaeus; Judas [not Iscariot], in Luke, is the son of James), and places of origin (Simon is a Canaanean; Judas is from Iscariot), and roles (Judas is a traitor; Matthew is a tax collector). There are also discrepancies between the lists: Thaddaeus (sometimes Labbaeus) in Matthew and Mark is absent in Luke, replaced by Judas son of James; Simon is not a Canaanean but a Zealot in Luke; John includes Nathanael of Cana with the Seven at the Sea of Galilee as if he is an apostle (and he is listed as one of the twelve in Epistle of the Apostles 2). As for other followers, only Luke mentions the 70 (or 72) disciples (10:1–20), but little is said of them; none of them are named.

The lists beg for explanation and, given the Christian urge to create new traditions, for expansion into a range of lists of the apostles documenting all manner of things: where they are from, the names of their parents, their tribes, where they preached, where and how they died, and in one notable list, the names of their wives and children. The disciples also receive attention with all 70/72 receiving names and other details.

The creation of these lists went hand-in-hand with the creation of apocryphal acts which document the exploits of the apostles as they take the Christian message to the four corners of the world. The most well-known apocryphal acts are the five earliest accounts—Peter, Paul, Thomas, Andrew, and John—composed at the end of the second and beginning of the third century. The same five apostles appear in our earliest expanded apostolic list in Origen, as preserved in Eusebius:

The holy apostles and disciples of our Saviour were scattered over the whole world. Thomas, tradition tells us, was chosen for Parthia, Andrew for Scythia, John for Asia, where he remained till his death at Ephesus. Peter seems to have preached in Pontus, Galatia and Bithynia, Cappadocia and Asia, to the Jews of the Dispersion. Finally he came to Rome where he was crucified, head downwards at his own request. What need be said of Paul, who from Jerusalem as far as Illyricum preached in all its fullness the gospel of Christ, and later was martyred in Rome under Nero?” (Eccl. Hist. 3.1, appealing to Origen’s Commentary on Genesis 3).

Origen gets his information from “tradition,” which suggests he is aware of the apocryphal acts or the traditions that they draw upon. Before long all of the other apostles and even secondary characters, such as Cornelius the Centurion, had their own acts, and some apostles received multiple versions of their exploits (e.g., Acts of John by Prochorus, the Acts of Thomas and His Wonderworking Skin). Add to these also numerous versions (sometimes translations, sometimes new accounts) in Latin (the Apostolic Histories collection), Coptic (translated into Arabic, then Ethiopic), as well as Syriac, Armenian, and other languages. There are obvious relationships between the lists and the activities reported of the apostles in the apocryphal acts but the nature of those relationships is not clear: are they derived from common traditions? Are the lists derived from the acts? Or vice versa? Or did they mutually influence each other?

The answers are not readily apparent because so few people have studied this material; with one exception, they do not appear in the major apocrypha compendia (German, Italian, English), and only a few scholars have devoted much time to them. The richest sources for the apostolic lists are the twin studies by Theodor Schermann from 1907; one volume (1907a) is editions (primarily Greek) the other is a discussion of their origins and relationships (1907b). Schermann was followed by François Dolbeau in a series of articles collected together in 2012; Dolbeau also translated two of the texts for the Écrits apocryphes chrétiens series (2005)—the only apocrypha compendium to include any of the apostolic lists. Dolbeau is now succeeded by Christoph Guignard who is preparing new editions of the Greek lists based on numerous additional sources (preliminary discussion in Guignard 2016). As for lists in languages other than Greek and Latin, Michel van Esbroeck (1994) published a few witnesses to Syriac lists and others to Armenian and Georgian. Versions also exist in Old English, Middle Irish, Church Slavic, and Sogdian. Brandon Hawk and I have been populating NASSCAL’s e-Clavis with entries on the texts, some of which include English translations.

The answers are not readily apparent because so few people have studied this material; with one exception, they do not appear in the major apocrypha compendia (German, Italian, English), and only a few scholars have devoted much time to them. The richest sources for the apostolic lists are the twin studies by Theodor Schermann from 1907; one volume (1907a) is editions (primarily Greek) the other is a discussion of their origins and relationships (1907b). Schermann was followed by François Dolbeau in a series of articles collected together in 2012; Dolbeau also translated two of the texts for the Écrits apocryphes chrétiens series (2005)—the only apocrypha compendium to include any of the apostolic lists. Dolbeau is now succeeded by Christoph Guignard who is preparing new editions of the Greek lists based on numerous additional sources (preliminary discussion in Guignard 2016). As for lists in languages other than Greek and Latin, Michel van Esbroeck (1994) published a few witnesses to Syriac lists and others to Armenian and Georgian. Versions also exist in Old English, Middle Irish, Church Slavic, and Sogdian. Brandon Hawk and I have been populating NASSCAL’s e-Clavis with entries on the texts, some of which include English translations.

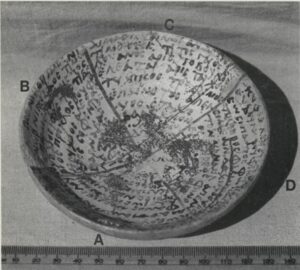

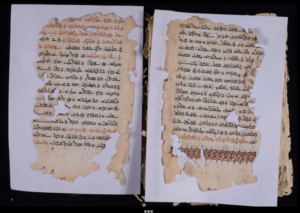

The lists circulated both independently and embedded in larger works. Even as independent texts, they can be found in interesting contexts—for example, the Syriac list attributed to Eusebius is frequently found in Peshitta manuscripts among other “supplementary” materials. As for examples of embedded texts, the Pseudo-Eusebius list also appears incorporated in Solomon of Basra’s Book of the Bee (and other Syriac historiographical works) and the Names of the Apostles and their Parents can be found in the Coptic Homily on Life and Passion of Christ by Pseudo-Cyril of Jerusalem. Apostolic lists also show up in other media. Three bowls have been found in Hambukol in Northern Sudan decorated with lists of the disciples and apostles in Greek (Hägg 1993). These bowls date from the late tenth or early eleventh century and seem to have been placed in the foundations of a building as a type of charm for protection. The lists are not identical with any known list; 18 names do not appear elsewhere. Another example of lists in other media is the frescoes in two tenth-century cave churches in Cappadocia: Kokar Kilise and Ayvali Kilise (see Thierry and Tenenbaum 1963). The frescoes feature two rows of six apostles holding a book or plaque with the name of their preaching location.

The following discussion will focus on the lists that are most germane to the topic of the interplay between the lists and apocryphal traditions. The first of these, and the earliest of the Greek lists, is Anonymus I. Only a handful of copies of this list remain because the list was replaced with expanded versions attributed to Epiphanius and Hippolytus. Four of the five Greek copies of the original list are found in New Testament manuscripts, serving, again, as “supplementary” material. The list is extant also in an early Ethiopian version translated directly from Greek, and a considerably damaged Latin manuscript from ca. 500. The text makes use of Origen via Eusebius so it cannot be earlier than the mid-fourth century. Anonymus I focuses on the apostles, presented in Matthew’s order and ending with Paul and Matthias; only a handful of disciples are mentioned (Titus, Crescens, Barnabas, Sosthenes, Barsabbas, Linus, Thaddaeus, Cleopas, and the Eunuch of Queen Candace from Acts 8), and then the list concludes with statements on the composition of the four canonical Gospels. Much of the information on the apostles could have been derived from Eusebius: Paul’s crucifixion under Nero, Bartholomew’s taking the Gospel of Matthew to the Indians, Matthew’s writing of his Gospel in Hebrew, the stoning of James the Just (assimilated with James, son of Alphaeus) in Jerusalem, Thaddaeus’s preaching in Edessa, and Simon the Canaanite’s succession of James as bishop of Jerusalem. The latter half of the list focusing on disciples credits the source as Clement of Alexandria’s Hypotyposeis, though likely via Eusebius (Hist. eccl. 1.12.2). Information not found in Eusebius appears in, and could be derived from, apocryphal acts: Andrew’s preaching audience (Scythia is mentioned by Origen, but Anon. I also says Andrew preached among the Sogdians and the Sacae), John’s writing of his gospel (not the apocalypse) on Patmos (as in the Acts of John by Prochorus), and Bartholomew’s martyrdom (his flaying is told in the Latin Passion of Bartholomew, though this may derive from earlier traditions that no longer survive). Also of interest in this list is the information provided for the Eunuch of Candace, who preached “in Arabia Felix and in the island of Ceylon, which is in the Red Sea, and it is reported that he was martyred there.” There are no known apocryphal texts about the Eunuch but Irenaeus was aware of traditions about him (Haer. 2.12.8), including his name: Simeon Bachus, though none of the list writers make use of this information.

The Ethiopic version of Anonymus I (as well as some Greek manuscripts) have some curious expanded readings, which could be original or reflect local (originally Egyptian) traditions. A few examples (in bold type) are presented below.

2. Andrew preached to the Scythians, to the Sogdians and to the Sacae. He died in Patras of Achaea.

4. John preached in Asia; exiled to Patmos because of the word of God, he wrote there the gospel. He died in Ephesus.

7. Thomas preached to the Parthians, to the Medes, to the Persians, to the peoples of Carmania, Hyrkania, Bactria, and Margiana. He died in the Indian town of Calamine.

8. Matthew, after having written the Gospel in the Hebrew language, he placed [it] in Sion. He died in the land of the priests in Parthia.

After Paul (Ethiopic) or Matthew (one Greek manuscript) is added: Mark preached to the Egyptians and to the inhabitants of Alexandria; the gospel he wrote in Rome was dictated to him by Peter. He died in Egypt, while he lived in the Capiton district; he was buried in Alexandria, in the Boukolou, inside a martyrium, with Victor, protomartyr of Lycopolis, who was moved by Alexander and deposited where all the bishops before Theonas rest.

Note particularly Matthew dying in the land of the priests in Parthia, which seems to be connected to the Coptic Acts of Matthew in the Land of the Priests. The Ethiopic’s lengthy addition on Mark has parallels in the Martyrdom of Mark, a text likely composed in Egypt. Given the amount of detail provided here, the Ethiopic translator probably knew the Martyrdom.

So how does Anonymus I relate to the apocryphal texts with which it shares information? Ivan Miroshnikov (2018:14–15), who works with Coptic apocryphal acts, argues that the Coptic Martyrdom of Andrew takes information about Andrew’s preaching areas (among the Sogdians and the Sacae) from this list, and that the Preaching of Philip relies on the list for mention of Philip’s preaching in Phrygia and burial in Hierapolis (2023:482). Jean-Daniel Kaestli and Janet Spittler believe the Acts of John by Prochorus depends on the list; on this theory, Spittler remarks: “Indeed, the basic outline of John’s activities in the earliest form of the apostolic lists—his initial presence in Asia, his exile to Patmos, and his composition of the Gospel there—tracks nicely with the basic plot structure of Acts John Proch.” (2023:273). Add to these examples the Coptic Martyrdom of James, Son of Alphaeus which reads as an expansion of the list’s mention of James (identified also as James the Just) as being stoned by the Jews in Jerusalem and subsequently buried near the temple. These theories seem sound. All of these texts are relatively late compositions—even Acts John Proch.—later than even the material remains of Anonymus I (ca. 500), never mind its time of composition. But it still begs the question of where did the compiler of the list get their information? Particularly the very curious notion that John wrote his Gospel on Patmos. Is this all the compiler’s invention, or were there earlier traditions drawn into the list just as it drew on the material from Eusebius?

The careers of the apostles are expanded further in Anonymus II, also called the Index Greco-Syrus because its locations for the apostles show the influence of eastern traditions. The information in this later list is more detailed and certainly seems to draw from apocryphal acts. Its focus on burial sites for the apostles affirms traditions that by this point in time were forming the basis of a bustling pilgrimage industry. The list of disciples (the earliest that is known) is drawn mostly from canonical sources, particularly Acts and Paul’s letters, for example:

16. Hermas, the shepherd, whom Paul salutes in his Letter to the Romans, within a group comprising: (17–23) Andronicus, Junias, Ampliatus, Urban, Rodion, Asyncritus, [and] Jason, whom Paul states was born before him in Christ.

24–30. The seven deacons, namely Stephen, Philip, Prochorus, Timon, Nicanor, Parmenas, Nicolas.

31–32. According to the testimony of the Book of Acts, when the Twelve gathered together the crowd of disciples, those who were sent to Antioch with Barnabas and Paul, namely Judas and Silas.

33. Silvanus, with whom Paul writes to the Thessalonians.

34. Simon, son of Cleopas, mentioned in the Gospel of John; he became bishop of Jerusalem and was martyred under Emperor Domitian in Caesarea Palestine, his head severed by the sword.

The names of those not mentioned in the New Testament, the author says, were found “in a manuscript.” The list of disciples also includes a number of heretics: 12 disciples apostatized with Cerinthus, but they were replaced with 10 others—a creative way of dealing with the discrepancy of 70 and 72 in Luke’s manuscript tradition.

Following in the same tradition as Anonymus I is the list attributed to Epiphanius. Of particular interest here is its description of Andrew, whose preaching area is expanded to include the Gorsinians, Sebastopolis Major, the fort of Asparus, the Port of Hyssos and the Phasis River, in the land of the Ethiopians (by which the author means northeastern Asia Minor). Epiphanius the Monk cites his namesake’s list as a source for his ninth-century reworking of Andrew traditions the Life of Andrew and goes on to describe Andrew’s travels in these areas. With Epiphanius the Monk we have unequivocal evidence of a writer of apocryphal tales of the apostles drawing information from a list and using it to create his text.

The list of Pseudo-Hippolytus is a separate development from Anonymus I, so it has agreements in its list of apostles with Ps.-Epiphanius but includes a different list of disciples. Of interest here is the focus on where each of the disciples served as bishop (e.g., Timon, bishop of Bostra; Parmenas, bishop of Soli; Nicolas, bishop of Samaria; Barnabas, bishop of Milan) and a note about Mark and Luke temporarily falling away from the faith: “These two belonged to the seventy disciples who were scattered by the offense of the word which Christ spoke, ‘Except a man eat my flesh, and drink my blood, he is not worthy of me.’ But the one being induced to return to the Lord by Peter’s instrumentality, and the other by Paul’s.” This may be another way to account for the conflicting traditions about 70 and 72 disciples.

The last of the major Greek lists is attributed to Dorotheus of Tyre, a third/fourth century bishop, though the text was composed much later. The lists are embedded in a larger narrative in which the Patriarch of Constantinople produces the text to demonstrate to Pope John I that the See of Constantinople was established before the See of Rome. The argument is based on the mention of Stachys in the list of disciples: “Stachys, whom the Apostle also mentions in the epistle to the Romans; whom also Andrew the apostle, traversing the sea of Pontus, in Argyropolis of Thrace appointed bishop of Byzantium.” This information is in turn used in the Story of Andrew, an eighth-century account of the apostle’s travels. Its itinerary agrees with Ps.-Dorotheus on Andrew and tells the story of Andrew stopping in Argyropolis to ordain Stachys as bishop of Byzantium. The direction of influence is somewhat complicated; it seems likely that Ps.-Dorotheus invented the Stachys tradition to serve his interests, and then the writer of the Story of Andrew, like Ephipanius the Monk, used the list as the basis for his account of Andrew’s travels.

The last of the lists to be covered is the main Syriac list of apostles and disciples, attributed to Eusebius of Caesarea. It appears typically in Peshitta manuscripts and in works by Solomon of Basra, Michael the Syrian, and others. A few Armenian lists also draw from it. What distinguishes this list is that, along with other information, the name of the tribe of each apostle is given.

Simon Peter and Andrew: Naphtali.

James and John, the sons of Zebedee: Zebulun.

Philip: Asher.

Bartholomew: Issachar.

Thomas: Judah.

Matthew: Issachar.

Simon: Ephraim.

Judas Thaddaeus/Lebbaeus: Judah.

James, son of Alphaeus: Manasseh.

Judas Iscariot: Dan

Matthias: Reuben.

Paul: Benjamin (or Ephraim).

The list also features two significant expansions. The first is an account of the discovery of Paul’s head and its reunion with his body; this story is found also in manuscripts of the Epistle of Pseudo-Dionysius to Timothy. The second focuses on John and tells how he journeyed to Asia Minor, was exiled to Patmos, and on his return to Ephesus he worked with Ignatius and Polycarp and consecrated Timothy as bishop—all of which is derived from the Acts of John by Prochorus. The list goes on to say that John died in Ephesus but did not want the location of his tomb to be known; the tomb of John that is known in Ephesus belongs to another John, the author of the Apocalypse and John’s disciple, who wrote down his every word—a clever way of making the Apocalypse Johannine even if it was composed by a different John. The list of disciples is once again quite different from the Greek lists, but what is particularly interesting are the three names that begin the list: Addai, Aggai, and Thaddaeus, all based in Edessa and obviously reflecting west Syrian traditions. A similar process is observed in Armenian lists, whether translations of Greek or Syriac lists or Armenian creations, which credit Bartholomew with evangelizing Armenia.

Lists, both in years past and today, are used to organize. The lists of apostles and disciples take various traditions and bring order to them; where did the apostles preach? Where are they laid to rest? Who were their parents? Their wives? And who are the 70 disciples anyway? Once created they become resources used by later writers to create new texts; and they get adjusted or created anew to reflect local traditions (like Addai in the Syriac list) and to support claims of authority in ecclesiastical disputes (like Andrew in the Byzantine lists). The amount of creativity in the lists of disciples is surprising. It is a similar phenomenon as the genealogies of Matthew and Luke, which commonly draw upon Hebrew Scriptures but go their own way when their sources run dry; so too the lists share some names because of the use of canonical and patristic texts, but there is much variation where the sources come up short. The lists, then, not only interact with apocryphal texts, they are apocryphal texts and should therefore receive more attention from apocrypha scholars. But note too that when inserted into Greek apostolos and Syriac Peshitta codices, they become canonical, taking on a level of authority that far surpassed that of the apocryphal acts. The line between apocrypha and canon is frequently blurry and the lists are another example of how orthodox Christian writers take from apocryphal texts whatever they see as valuable and discard the rest.

Works Cited

Dolbeau, François. 2005. “Listes d’apôtres et de disciples.” Pages 415–80 in Écrits apocryphes chrétiens. Vol. 2. Edited by Pierre Geoltrain and Jean-Daniel Kaestli. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade 443. Paris: Gallimard.

_____. 2012. Prophètes, apôtres et disciples dans les traditions chrétiennes d’Occident: Vies brèves et listes en latin. Subsidia Hagiographica 92. Brussels: Société des Bollandistes.

Esbroeck, Michel van. 1994. “Neuf listes d’apôtres orientales.” Aug 34: 109–99.

Guignard, Christophe. 2016. “Greek Lists of the Apostles: New Findings and Open Questions.” ZAC 20: 469–95.

Hägg, Tomas. 1993. “Magic Bowls Inscribed with an Apostles-and-Disciples Catalogue from the Christian Settlement of Hambukol (Upper Nubia).” Or 62: 376–99.

Miroshnikov, Ivan. 2018. “The Coptic Martyrdom of Andrew.” Apocrypha 29: 9–28.

_____, trans. “The Preaching of Philip: A New Translation and Introduction.” Pages 479–505 in vol. 3 of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Edited by Tony Burke. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2023.

Schermann, Theodor. 1907a. Propheten- und Apostellegenden nebst Jüngerkatalogen des Dorotheus und verwandter Texte. TUGAL 31/3. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

_____. 1907b. Prophetarum vitae fabulosae, indices apostolorum discipulorumque Domini, Dorotheo, Epiphanio, Hippolyto aliisque vindicata. Leipzig: B. G. Teubneri.

Spittler, Janet E., trans. 2023. “The Acts of John by Prochorus.” Pages 262–361 in vol. 3 of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Edited by Tony Burke. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Thierry, Nicole, and A. Tenenbaum. 1963. “Le Cénacle apostolique à Kokar Kilise et Ayvali Kilise en Cappadoce: Mission des apôtres, Pentecôte, Jugement dernier.” Journal des Savants: 228–41.

Hi Tony, the following are the chosen twelve disciples of Jesus according to an eyewitness:

1 – Nicodemus who was the author of the Gospel of John, John + Thomas and the Gospel of Thomas which he wrote/created with the Holy Ghost.

2 – Joseph of Arimathaea who was the father of Jesus (*Salome was the mother of Jesus, May called Magdalene was Jesus’s sister – his brothers did not believe in him).

3 – Simon called Peter.

4 – Andrew who was Peter’s brother.

5 – Philip.

6 – Nathanael.

7 – Lazarus (the same Enoch/Elijah who just died for the first time since the beginning.

8 – Thomas called Didymus.

9 – Judas not Iscariot.

10 – *James (son of Zebedee).

11 – *Matthew (son of Zebedee).

12 – Judas called Iscariot who betrayed Jesus (John who baptized with water is actually the twelfth).

Now you know why certain *names were left out of the Gospel of John and revealed in the Gospel of Thomas. Now you will see how John + Thomas exposes the synoptic gospel writers as nothing more than thieves and liars. The proof is contained in my Home Page and my Introduction Page (http://onemosesnicodemus.com). Stop spreading lies. – Peter