On Indexing More New Testament Apocrypha vol. 3

The indices for New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures vol. 3 have just been completed and sent off to the publisher. Indexing a book of this size (650 pages) takes a month of full-time work; so all non-essential activities—research, administrative tasks, sleep—had to be put on hold. But now I can move on, happy that the final step in the publication process is complete. So what is the first thing I do with this newfound freedom? Write a blog post about it.

The indices for New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures vol. 3 have just been completed and sent off to the publisher. Indexing a book of this size (650 pages) takes a month of full-time work; so all non-essential activities—research, administrative tasks, sleep—had to be put on hold. But now I can move on, happy that the final step in the publication process is complete. So what is the first thing I do with this newfound freedom? Write a blog post about it.

In part, I just want to take an opportunity to vent a little about the frustrations of indexing, but I think some might wonder how indices are prepared, particularly for a project of this size and scope. Their first question might be why I don’t pay someone else (like a graduate student) to do it. Indexing is definitely the “grunt work” of publishing, an onerous task unworthy of a senior scholar’s time and attention (sarcasm alert!), and a graduate student could certainly use the experience and compensation. But I don’t have graduate students, or money. And I also prefer to do this work myself because of its complications. Indexing gives an author/editor a chance to catch lingering errors before the book goes to press. Despite an already rigorous process of proofreading—by the authors, then me, the publisher’s copyeditor, and the authors and me again—mistakes sneak through, and every one that makes it to the printed page is a dagger to the heart. And with my high blood pressure (maybe I should sleep more), I can’t take many of those.

This is my tenth go round at indexing and I have the process down to a science. It is surprisingly old-school. You would think that some electronic search and organization process would get the job done in no time, but as my publisher’s Guide to Preparing Indexes states, “There really is no substitute for rereading the whole work and preparing an index yourself.” Still, I have been able to create a few shortcuts.

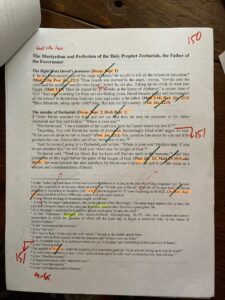

At the final stage of editing, I print off all the chapters and do a final pre-submission proofreading. As I work through the chapters, I use two highlighters to flag primary and secondary source references (three highlighters if the project includes a subject index). When further changes are made in subsequent stages, I write these onto the printed pages. Then when the indexing proofs come in, I add the page numbers and footnote numbers in the translations (which renumber every page, so they are not finalized until this stage). I end up with some pretty messy pages.

At the final stage of editing, I print off all the chapters and do a final pre-submission proofreading. As I work through the chapters, I use two highlighters to flag primary and secondary source references (three highlighters if the project includes a subject index). When further changes are made in subsequent stages, I write these onto the printed pages. Then when the indexing proofs come in, I add the page numbers and footnote numbers in the translations (which renumber every page, so they are not finalized until this stage). I end up with some pretty messy pages.

I do the author index first, since it is the least complicated. For MNTA 3, I already had the alphabetical list prepared, by simply copy and pasting the bibliographies and footnotes and trimming down the material. I did this prior to submission of the manuscript so that I could standardize the bibliographical references to frequently cited works. For this index I could simply search the PDF and write in the page numbers where the authors’ names appear but going through the manuscript a page at a time allows me to catch any missing or misspelled names. Nevertheless, I did check all of my data by searching and was able to correct a number of errors—I’d even skipped two whole chapters! And I also discovered other mistakes that had evaded previous stages of proofreading, including an entire footnote that had been accidentally erased by the typesetters.

Work on the ancient texts index had also been started prior to submission so that I could ensure the titles were consistent throughout the volume (and with previous volumes). I began with the list from vol. 2 and then added in new texts at the end of the document, expecting to assign them to the appropriate columns when the time came to finish the index. The ancient text index is far more time-consuming and cannot be checked by searching the file, given that citations do not always include the texts’ titles. Some massaging of the data was made in the process—e.g., a reference to the return from Egypt by one author as Matt 2:19–22 and another as 2:19–23 were reconciled, as were competing references to the same work appearing in its English and Latin titles (e.g., Adso of Montier-en-Der’s De ortu et tempore Antichristi appeared also as Letter on the Origin and Time of the Antichrist and, erroneously as De ortu et obitu Antichristi), and different methods of dividing texts (e.g., Josephus, standardized to the Niese, rather than Whiston, divisions).

The final reconciliation problem I faced took hours to fix. One of my own contributions, the Decapitation of John the Baptist, features a reference to the Chronicon Paschale 350. Two other contributors also cited the text but by volume and page numbers of the critical edition (fortunately available on Archive.org). So I had to go back to the edition and figure out the best method to cite the text. I noticed other authors who have worked with Chron. Pasch. use “s.a.” in their references—which refers to the year covered by the chronicle. And these numbers do appear in the edition, though they are not readily apparent on the page. But why did my reference have “350”? Was it “s.a. 350”? No. Page 350? No. I had to go back to where I first saw the reference: Athanasius Vassiliev’s Anecdota graeco-byzantina. He simply said that the portion of Chron. Pasch. relevant to my discussion appeared on vol. 2, p. 138 of the same edition used by my other contributors. And there I saw “V 350” in the margin, but I have no idea what that signifies (page number of the manuscript?). But the bigger issue is that vol. 2 is not the text of Chron. Pasch. after all but a collection of parallels. The actual text in this section of the volume was the List of the Apostles and Disciples attributed to Dorotheus of Tyre. So after cursing the ghost of Vassiliev, I made the necessary changes to the manuscript, breathing a heavy sigh of relief that the error was fixed before publication. It may not seem like this should have taken hours, but there is not that much scholarship on Chron. Pasch. to check for standard practices and the introductions in nineteenth-century critical editions (written in Latin!) are not particularly forthcoming in disclosing their sources and methods.

In the end the proofs flag 224 changes, which is not too bad at this stage. I requested 959 changes to the first proofs, though half of those were typesetting issues. There is one error that I just had to leave because it would have upset the pagination too much; but it will forever irritate me, despite the fact that probably no one else will ever notice it. If you want a preview of the finished product, check out the proofs on display at the Eerdmans booth at SBL. The book is scheduled for release in May, but you can preorder it now.