Orthodoxy and Heresy in the Pseudo-Apostolic Memoirs

My next bog publishing project (well, while continuing to edit volumes of More New Testament Apocrypha) is a comprehensive introduction to Christian Apocrypha for the Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library series. While certainly a prestigious assignment, it’s pretty intimidating—so many texts, so little space, so little time! Initially I promised to submit a draft at the end of two years. But I ended up spending the first of those years just clearing my schedule of other writing projects. And though I said I would not take on anything new, I have been sidetracked by the occasional conference that was in far too interesting a place to pass up. I did start writing, but instead of beginning with an easy chapter on, say, infancy gospels, I decided to start with something far more challenging: pseudo-apostolic memoirs. My progress was made slower because I was compiling, at the same time, entries on each of the texts for e-Clavis (click on the titles of the texts below to see the entries). The memoirs are difficult because there is still so much work to be done on simply establishing the texts—either because the Coptic manuscripts are dispersed in libraries all over the world, or because the texts are now extant only in Ethiopic and/or Arabic and few people in our field work in these languages. But I find the memoirs really fascinating and one of my goals for this project is to integrate them more into the “canon” of Christian apocrypha. So I plan to give them more space than they usually get in apocrypha collections and studies. This post is a summary of some of what I learned while working on the chapter (submitted to my editor yesterday) with a list of work that still needs to be done on the material (so if anyone is looking for a new project . . . ).

The pseudo-apostolic memoirs—also called “diaries of the apostles” or simply “apostolic memoirs”—are Coptic texts (and translations into Arabic and Ethiopic) that combine apocryphal materials, often in the form of a post-resurrection dialogue between Jesus and the apostles, with exhortations to celebrate a particular feast day in the Coptic-Ethiopic liturgical calendar. Investigation into the pseudo-apostolic memoirs has been led by two scholars: Joost Hagen and Alin Suciu. Hagen first examined the material in 2004 (in “The Diaries of the Apostles: ‘Manuscript Find’ and ‘Manuscript Fiction’ in Coptic Homilies and Other Literary Texts,” in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies, Leiden, 27 August–2 September 2000 [edited by Mat Immerzeel and Jacques van der Vliet; 2 vols.; OLA 133; Leuven: Peeters, 2004], 1:339–71) and divided the texts into two sub-categories: “manuscript fiction,” which includes texts directly attributed to apostles or disciples of apostles, and “manuscript find,” in which the apocryphal text is said to have been discovered, typically, in a house or library in Jerusalem, and is framed by a homily written by a well-known pre-Chalcedonian writer, such as Cyril of Jerusalem or Theodosius of Alexandria. Suciu finetuned this definition in his 2013 dissertation (published in 2017 as The Berlin-Strasbourg Apocryphon: A Coptic Apostolic Memoir [WUNT 370; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck]), presenting an extensive list of all known representatives of the genre, divided between those embedded within a homily, those that are not, and those that are too fragmentary to determine their context. He also notes several other common features, such as Jesus’ frequent address to the apostles as “O holy members/O honored members,” an expression drawn from the letters of Paul (see 1 Cor 6:15, 12:12–31; Rom 12:3–5; Eph 4:25, 5:30) and statements of Miaphysite Christology. Suciu places the origins of the memoirs in the context of fifth-century Christological debates, specifically after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE.

The pseudo-apostolic memoirs—also called “diaries of the apostles” or simply “apostolic memoirs”—are Coptic texts (and translations into Arabic and Ethiopic) that combine apocryphal materials, often in the form of a post-resurrection dialogue between Jesus and the apostles, with exhortations to celebrate a particular feast day in the Coptic-Ethiopic liturgical calendar. Investigation into the pseudo-apostolic memoirs has been led by two scholars: Joost Hagen and Alin Suciu. Hagen first examined the material in 2004 (in “The Diaries of the Apostles: ‘Manuscript Find’ and ‘Manuscript Fiction’ in Coptic Homilies and Other Literary Texts,” in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies, Leiden, 27 August–2 September 2000 [edited by Mat Immerzeel and Jacques van der Vliet; 2 vols.; OLA 133; Leuven: Peeters, 2004], 1:339–71) and divided the texts into two sub-categories: “manuscript fiction,” which includes texts directly attributed to apostles or disciples of apostles, and “manuscript find,” in which the apocryphal text is said to have been discovered, typically, in a house or library in Jerusalem, and is framed by a homily written by a well-known pre-Chalcedonian writer, such as Cyril of Jerusalem or Theodosius of Alexandria. Suciu finetuned this definition in his 2013 dissertation (published in 2017 as The Berlin-Strasbourg Apocryphon: A Coptic Apostolic Memoir [WUNT 370; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck]), presenting an extensive list of all known representatives of the genre, divided between those embedded within a homily, those that are not, and those that are too fragmentary to determine their context. He also notes several other common features, such as Jesus’ frequent address to the apostles as “O holy members/O honored members,” an expression drawn from the letters of Paul (see 1 Cor 6:15, 12:12–31; Rom 12:3–5; Eph 4:25, 5:30) and statements of Miaphysite Christology. Suciu places the origins of the memoirs in the context of fifth-century Christological debates, specifically after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE.

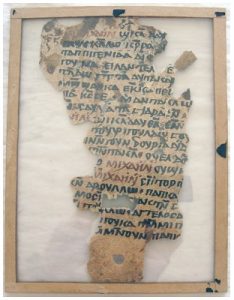

Some of these memoirs are fairly well-known. The History of Joseph the Carpenter has appeared in Christian apocrypha collections for centuries, and the Berlin-Strasbourg Apocryphon (first published by Charles Hedrick and Paul Mirecki as the Gospel of the Savior) is a recent addition. Fragments of other texts have appeared in classic works by Forbes Robinson (Coptic Apocryphal Gospels, 1896) and Eugène Revillout (Les apocryphes coptes, 1904). But early scholars of these materials assumed they were translations of earlier Greek texts; with Hagen’s and Suciu’s work, the texts can now be evaluated in their appropriate context. Investigation into the memoirs is complicated by the condition of the manuscripts. While some texts are complete and others survive in multiple witnesses, many of the manuscripts are either heavily damaged or were dismembered and sold in pieces to various institutions. Study of these texts entails the painstaking reassembly of the fragments. Some of the texts no longer survive in Coptic at all, but can be found in translations into Arabic (including Garšuni) and Ethiopic; there are even a few scraps in Old Nubian and another in Greek (though likely a translation from Nubian).

One of the fruits of all this labor is the creation of new editions and translations incorporating the newly identified and reassembled manuscripts; several of these translations have appeared in the MNTA volumes: the Berlin-Strasbourg Apocryphon (by Alin Suciu), the Discourse of the Savior and the Dance of the Savior (by Paul C. Dilley), the Encomium on Mary Magdalene (by Christine Luckritz Marquis), the Encomium on John the Baptist (by Philip L. Tite), the Investiture of Abbaton (by Alin Suciu), the Homily on the Life of Jesus and His Love for the Apostles (by Timothy Pettipiece), the Homily on the Passion and Resurrection by Pseudo-Evodius (by Dylan M. Burns), the Book of Bartholomew (by Christian H. Bull and Alexandros Tsakos), the Homily on the Building of the First Church of the Virgin by Pseudo-Basil of Caesarea (by Paul C. Dilley), the Mysteries of John (by Hugo Lundhaug and Lloyd Abercrombie), the Investiture of the Archangel Michael (by Hugo Lundhaug), and the Investiture of the Archangel Gabriel (by Lance Jennott).

One of the fruits of all this labor is the creation of new editions and translations incorporating the newly identified and reassembled manuscripts; several of these translations have appeared in the MNTA volumes: the Berlin-Strasbourg Apocryphon (by Alin Suciu), the Discourse of the Savior and the Dance of the Savior (by Paul C. Dilley), the Encomium on Mary Magdalene (by Christine Luckritz Marquis), the Encomium on John the Baptist (by Philip L. Tite), the Investiture of Abbaton (by Alin Suciu), the Homily on the Life of Jesus and His Love for the Apostles (by Timothy Pettipiece), the Homily on the Passion and Resurrection by Pseudo-Evodius (by Dylan M. Burns), the Book of Bartholomew (by Christian H. Bull and Alexandros Tsakos), the Homily on the Building of the First Church of the Virgin by Pseudo-Basil of Caesarea (by Paul C. Dilley), the Mysteries of John (by Hugo Lundhaug and Lloyd Abercrombie), the Investiture of the Archangel Michael (by Hugo Lundhaug), and the Investiture of the Archangel Gabriel (by Lance Jennott).

My plan was to group all of the memoirs together in one chapter, rather than to divide them across chapters according to their subject matter. For example, most apocrypha collections place the History of Joseph the Carpenter with infancy narratives, though more as a counterpart to the story of Mary in the Protevangelium of James than because it contains stories of Jesus’ childhood (though it does contain a few allusions to material from Prot. Jas. and Infancy Thomas). The text is better understood, however, when read alongside other Coptic memoirs, particularly those that also mention Egyptian death and burial practices, such as the Book of Bartholomew and several Dormition texts. Another example is the Lament of the Virgin, which sometimes appears in apocrypha collections under the title Gospel of Gamaliel because previous scholars have argued that it incorporates an otherwise lost early passion gospel related to the Pilate Cycle of texts. But it is likely a Coptic composition. Some of the memoirs proved tricky to categorize. Would it be better to place the Homily on the Dormition attributed to Evodius of Rome with the two other Evodius homilies or with the larger category of Dormition traditions? What about the Homily on the Flight to Egypt attributed to Cyriacus of Behnesa? It features the usual memoirs motif of manuscript discovery but it is an adaptation of the Vision of Theophilus; perhaps both of these should be placed together with infancy gospels. In the end I decided to keep Dormition traditions together but divide the Flight to Egypt material; I may yet change my mind.

In reading the memoirs I was struck by how similar they are in some ways to so-called “gnostic” literature. The Secret Book of John, for example, features a post-resurrection dialogue between Jesus and John about the secrets of the cosmos. Many of the memoirs also involve dialogues between one or more apostles and the risen Jesus, typically set on the Mount of Olives. The Mysteries of John even features Jesus instructing John, mostly through a cherub mediator, about the order of the universe; in others, such as the Investiture of the Archangel Michael, depict Jesus describes the creation of humans and the fall of the devil—familiar themes in “gnostic” texts. Some of the memoirs even use gnostic terminology—such as Saklataboth (the name for the devil in Investiture of Michael, Investiture of the Archangel Gabriel, and the Encomium on the Four Bodiless Creatures), and Demiurge (a title given to God in Encom. 4 Creat.). These similarities demonstrate to me that the boundary between orthodoxy and heresy in Egypt is rather blurry and that orthodox Miaphysite monastics would find the texts from Nag Hammadi less unsettling and peculiar than we do.

And while on the topic of orthodoxy, it must be mentioned that the memoirs are the medieval Coptic and Ethiopic churches’ equivalent of the Greek Orthodox Synaxarion: stories of the saints read in public on feast days. The memoirs are each assigned to a specific date, many of which are retained in the official Coptic and Ethiopic Synaxaria. Some are grouped together in the manuscripts as one-stop sources for use on feast days, such as the manuscript MONB.NT, which contains at least six homilies, or the Ethiopic homily collections for the festivals of Mary (Dersanä Maryam) and Michael (Dersanä Mika‘el). Of particular interest is the integration of the Lament of the Virgin into the Ethiopic Readings for Holy Week (Mäshafä Gebrä Hammamat). The category “apocryphal” does not adequately describe these texts and the ways they have functioned in the Coptic church, and continue to function in the Ethiopic.

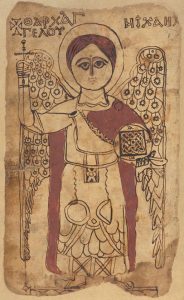

The memoirs also play a part in breaking down the artificial boundary between orthodox ritual and so-called “magical” practices. Several of the homilies focus on the archangel Michael, second only to the Virgin Mary in his esteem throughout the Christian world. Every month in the Coptic and Ethiopic calendars includes a feast day for Michael, each one corresponding to Michael’s descents to earth, both biblical and post-biblical. His name and image appear also on amulets, ceramic vessels, church walls, and funerary stelae. In the Encomium on the Archangel Michael by Pseudo-Timothy Aelurus, an angel who accompanies the apostle John in the memoir portion of the text, and the homilist, Ps.-Timothy, recommend several apotropaic uses of Michael’s name: writing it on the four corners of one’s house, inside and outside, and on the edges of clothing, on a table where people eat, as well as on platters and cups. Another link between apotropaic practices and Coptic traditions about Michael can be found in the Praise of Michael the Archangel extant in P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 686 (from the second half of the tenth- century). The last page of the manuscript features an image of Michael similar to an image of Michael in the manuscript containing Ps.-Timothy’s homily and Iain Gardner and Jay Johnston (“‘I, Deacon Iohannes, Servant of Michael’: A New Looks at P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and a Possible Context for the Heidelberg Magical Archive,” Journal of Coptic Studies 21 [2019]: 29-61) have argued that the “Deacon Iohannes” who created this and several other Heidelberg texts, may have worked at the Monastery of Michael in Hamuli, the site of composition also of two of the manuscripts of the Investiture of Michael.

Anyone interested in working on the memoirs, and has some skills in Coptic, Arabic, and/or Ethiopic, would find plenty of opportunities to help make these texts available for study by modern readers. Two of the homilies attributed to Cyril of Jerusalem, the Homily on the Resurrection and the Passion and the Homily on the Life of the Virgin, have not yet been published in full, despite the availability of complete Coptic manuscripts of these texts at the Morgan Museum and Library. Readings from another text, an anonymous Homily on the Virgin Mary containing material parallel to portions of the Protevangelium of James, are given in Robinson’s Coptic Apocryphal Gospels, and other portions have appeared since, but as yet there has not appeared a complete edition incorporating all of the witnesses, though Roelof van den Broek did promise one back in 1972. Several homilies on the Dormition—by Pseudo-Cyril of Jerusalem, Pseudo-Cyril of Alexandria, and Pseudo-Cyriacus of Behnesa—exist today only in Arabic (and Ethiopic for Cyriacus) and these have appeared so far only in Spanish translation (in Pillar González Casados, “Las relaciones lingüisticas entre el siriaco y el árabe en textos religiosos árabes cristianos,” PhD diss., Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2000).

The situation is similar for other homilies attributed to Cyriacus of Behnesa. A few Coptic fragments of the Lament of the Virgin have been recovered but the full text is available in Garšuni and Ethiopic. The editions in these languages are based on only a few sources but the manuscript tradition is quite rich and could use more attention. Its “sequel,” the Martyrdom of Pilate, has received much less attention. It has appeared so far in one Garšuni, one Arabic, and two Ethiopic editions, all based on manuscripts missing different portions of the text. A study that integrates all of this evidence would be very useful. The Homily on the Flight to Egypt comes in two versions: one that tells of the Holy Family’s stay in the monastery of Paisus (Dayr al-Garnus), and the other telling essentially the same stories but placing the activity at Dayr al-Muharraq (in al-Qusiyyah). So far only summaries of these texts have been published, based on a single Arabic manuscript, but other Arabic manuscripts are available and the text exists also in Ethiopic.

Finally, the Encomium on John the Baptist, attributed to John Chrysostom, has been published from two Coptic manuscripts, only one of which is complete. Translations may exist also in Arabic and Ethiopic—catalog descriptions can be vague, so it is uncertain that the texts are the same; only a look at the manuscripts would settle the issue. Another Ps.-Chrysostom homily reporting a dialogue between Jesus and the apostles on the Mount of Olives is found in a single Arabic manuscript at Dayr Qiddis Anba Maqqar. Not much was known about this text at the time of the publication of Suciu’s thesis but he has recently obtained a copy of the manuscript and is preparing an edition and translation.

There is far more I could say about the memoirs but blog posts should only be so long, and this one is pushing the limits. I do hope more Christian apocrypha scholars turn their attention to these texts, not only to aid in their reconstruction and translation but to integrate them into our understanding of how apocryphal texts function, particularly in corners of the world that are not examined with the same depth as the Latin and Greek churches.