2019 SBL Diary: Day Two

My second day at the 2019 SBL Annual Meeting began with the Journal of Biblical Literature editorial board breakfast meeting. If you ever submit a paper to the journal on the subject of Christian apocrypha, there’s a good chance I’m Reviewer 2. The discussion at the meeting focused on reducing the backload of submissions to the journal. But the really interesting talk was happening at my table. One person (who will not be named) mentioned to me that a certain scholar (who will not be named) was working on a complete version of an otherwise fragmentary apocryphal text (which will be named): the Gospel of Mary. The text is presently extant in an incomplete Coptic manuscript (the Berlin Codex) and two small Greek fragments. A complete text certainly would be a major contribution to work on this text, but some things about the rumor did not sound right. It is not out of the question that someone is working on this new manuscript, but probably not the person who was mentioned to me. Let’s hope there is some truth to the rumor.

Filled up on tea and pastries, I headed off to the first session of the Christian Apocrypha Section. The open session featured four papers on a variety of topics. Up first was Adeline Harrington (University of Texas at Austin) with “Apocryphal Oxyrhynchus: The Literary Landscape of a Late Antique City.” Harrington began with the statement by a late antique writer on Oxyrhynchus (I wish I could remember who) as a city “devoid of heretics,” yet manuscripts found at Oxyrhynchus contain a number of apocryphal texts, even as late as the sixth and seventh centuries. These later manuscripts feature acts and legends, rather than gospel-like texts as in the early period (e.g., Gospel of Peter, Gospel of Thomas). Harrington rightly noted that the later material receives less attention in scholarship than the more sensational earlier fragments. But I take issue with equating noncanonical texts with heresy. Many of these texts—particularly the acts and legends, such as the Acts of Paul—continued to be valued by orthodox churches, though not has highly as the texts of the canon. So, the late antique materials found at Oxyrhynchus do not make the city’s use of apocrypha particularly special—the same texts can be found in a multitude of medieval Greek and Syriac manuscripts (and other languages besides). Now if copyists at Oxyrhynchus continued to transmit so-called “gnostic” texts (e.g., Apocryphon of John, Gospel of Mary) after the fourth century, that would be a different story.

Harrington was followed by Rick Brannan (Faithlife/Appian Way Press) with his retitled paper “Five Agrapha from Fragmentary Early Christian Papyri.” The paper is the fruits of Brannan’s work transcribing and translating early Christian papyri; he circulates his results on his online newsletter (forthcoming). You can also read his entire paper on his web site at this location. By way of summary, the paper presents material from three papyri: 1. P. Amh. Gr. 12 (4th cent.), which features an acrostic hymn with two sayings (“I give my back, so that you may not experience death,” and “‘The poor [shall possess] a kingdom, theirs is the inheritance”); 2. P. land. 5.69 (4th cent.), which, reconstructed looks like a combination of John 12:32 and 17:10 (“I will draw everyone to myself” and “all my things are yours and your things are mine”); and 3. P. Gen. 3.125 (ca. 150–250), which contains two or three homilies, one of which has the saying, “When the hands start upon that house, and the son of peace is there, in that place your peace dwells. But if not, it will return to you,” and the second has, “Nothing happens apart from the will of God, not a sparrow will fall into a snare.” Brannan points out that little attention has been paid to these texts since their publication, particularly in collections of agrapha (certainly they are not cataloged in William D. Stroker’s Extracanonical Sayings of Jesus).

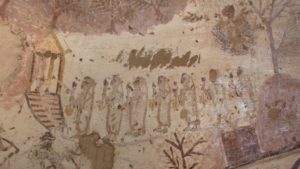

The second half of the session focused on images rather than texts. Emily Laflèche (University of Ottawa) began with “Temple, Tomb, Thecla? The Heavenly Ascent of the Seven Virgins and the Curious Connection to Thecla in the Exodus Chapel at El-Bagawat.” The paper was much the same as her contribution to the Material of Christian Apocrypha Conference held at the University of Virgina last year. The Exodus chapel is situated in one of the oldest Christian cemeteries (5th/6th cent.). Its crude wall paintings include three related images: Thecla being burned alive, seven women bearing torches walking toward a building, and an orans. The women are labeled “virgins” and Thecla too is named, though someone in the past fifty years has covered over the writing. Laflèche sees the image as evidence of a funerary procession ritual in which the soul is guided to a heavenly temple. No single text testifies to this ritual, but there are hints at it in several sources, including the Pistis Sophia, the Exegesis on the Soul, the Gospel of Philip, and two Valentinian funerary inscriptions (NCE 156 and the gravestone of Flavia Sophe). In the question period, Janet Spittler noted that scholars tend to look for texts to explain images; Laflèche’s paper shows how this is not always possible, at least not completely and in one location. Ally Kateusz added that women in such images are typically interpreted symbolically, but this is never the case with images of men.

The final paper was a bit of a departure as it focused on a text, the Shepherd of Hermas, that is noncanonical but not really apocryphal—in that it does not feature tales or sayings of first-century Christian figures. In “The Salvific Tower of the Shepherd of Hermas in Early Christian Reception,” Rob Heaton (University of Denver) took us on a tour of the Catacomb of San Gennaro in Naples which contains an image of the women building the celestial tower that will be home to those who achieve salvation (Herm. Vis. 3.5.1–3 [13.1–3]). This is the only known image related to Hermas; the catacomb features two other Christian images—one of Adam and Eve and the other (perhaps) of David and Goliath—but the others are all non-Christian. Heaton’s paper illustrated effectively the importance of this text in the early Christian centuries and, along with Laflèche’s, that Christians frequently turned to noncanonical texts and traditions for understanding not only their place in this world but also in the next.

Many of the panellists and audience members stuck around after the papers for the section’ s business meeting, and between us all we came up with four possible sessions for next year: 1. a discussion panel related to MNTA 2, which will be released in Spring (not so much a review panel, but something like, where do we go from here with these new texts?), 2. a session drawing on the work of Tobias Nicklas’ Beyond Canon project in Regensburg, 3. an open session, 4. and a joint session and/or something on later apocryphal acts such as the Virtutes Apostolorum.

After lunch (second breakfast?) it was time for the second Christian Apocrypha Section session, this one a combination of two themes: collectors of apocrypha and orphan apocrypha. The first presenter was Christoph Markschies (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin – Humboldt University of Berlin) with “Edgar Hennecke: A Non-Harnackian View on the Apocrypha by a Pupil of Harnack.” I really think it’s fascinating to delve into the background of apocrypha collections and their compilers. And Markschies revealed a lot. The first Hennecke volume appeared in 1904, along with a companion Handbuch. The project was born out of the press’s desire to have a New Testament Apocrypha counterpart to their two-volume collection of Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (Emil Kautzsch, Apocryphen und Pseudepigraphen des Alten Testaments, 1900). The preceding German collection, Karl Friedrich Borberg’s Bibliothek der neutestamentlichen Apokryphen, gesammelt, übersetzt, und erläutert (1841), was influential for Hennecke but he felt it was incomplete. Hennecke drew only on texts written before Origen, who marked the end, for Hennecke, of the first epoch of Christian history; he also incorporated texts of the Apostolic Fathers. Reviews of the collection by Albrecht Dietrich and Walter Bauer were critical of Hennecke for stopping with Origen, so Hennecke answered these criticisms with a single-volume revision in 1924 that included more texts but all still composed prior to Origen.

From Germany we moved over to England with “A Haunted Scholar: M.R. James and the Apocryphal Impulse,” presented by Stephen Hopkins (University of Central Florida). James had a lifelong dream of discovering apocryphal texts. To that end he mastered Greek and Latin by the age of ten, and Ethiopic by 15. As an adult he would approach libraries to catalog their holdings just so he could find more texts. James had a secondary, but as Hopkins demonstrated, related interest in ghost stories. In his introduction to a recent collection of James’s works, Darryl Jones calls him “the very greatest ghost story writer,” and most people know him more for his fiction than his scholarship. But the two interests certainly overlap, as many of the tales involve manuscripts and apocrypha. James’s family and friends were not particularly supportive of his work in either area. A. C. Bens, a close friend, said “No one alive knows so much or so little worth knowing.” I was aware of James’s ghost stories but did not know that they integrated his interest in apocrypha; I made sure to add The Collected Ghost Stories of M. R. James onto my Christmas list as soon as I got home.

After a short break, we turned to the second theme of the session: orphan apocrypha. These are stories that weave in and out of the manuscript tradition and tend to get lost in the notes to critical editions. The MNTA volumes try to bring attention to this material, so far including two tales of the Good Thief and the story of John and the Robber. My paper, “Four Syriac ‘Orphan’ Apocrypha Relating to the Birth and Death of Jesus,” examines a group of texts listed in Geerard’s Clavis apocryphorum Noui Testamenti under epistles (though some of them are better categorized as testimonia). These texts are: 1. the Epistles of Longinus and Augustus, 2. the Testimony of Ursinus, 3. and the two-part Dialogue of Patrophilus and Ursinus. They were published (in part) as appendices to Ignatius Rahmani’s edition of the Syriac Acts of Pilate in 1908. They are excerpted also in a number of other texts: the Chronicum maroniticum, Theodore Bar Konai’s Liber Scholiorum, the Chronography of Bar Hebraeus, Solomon of Basra’s Book of the Bee, the Chronicle of Michael the Syrian, and in Arabic in Agapius of Hierapolis’ Kitav al-‘unvan. Part way through working on the material, I came across Yury Arzhanov’s Syriac Sayings of Greek Philosophers (Peeters, 2019), which includes an edition of the complete text from which Rahmani excerpted the testimonia. My contribution to the study of this material is the mention of several additional manuscripts of the Sayings of Greek Philosophers and the placing of the testimonia into the broader phenomenon of having so-called “pagan” philosophers acknowledge the life and activities of Jesus and other early Christian figures. The most well-known example of this literature is the Epistles of Paul and Seneca, but I added also several testimonia appended to the Epistles of Pilate and Herod and the Testimonium Longinus. The latter text is a list of Greek rhetoricians, including Paul, attributed to Cassius Longinus, a third-century rhetorician and philosopher; the text is found in three Greek gospels manuscripts. The testimonia will be included in MNTA 3; in the meantime, information about the texts can be found on e-Clavis (HERE and HERE).

After a short break, we turned to the second theme of the session: orphan apocrypha. These are stories that weave in and out of the manuscript tradition and tend to get lost in the notes to critical editions. The MNTA volumes try to bring attention to this material, so far including two tales of the Good Thief and the story of John and the Robber. My paper, “Four Syriac ‘Orphan’ Apocrypha Relating to the Birth and Death of Jesus,” examines a group of texts listed in Geerard’s Clavis apocryphorum Noui Testamenti under epistles (though some of them are better categorized as testimonia). These texts are: 1. the Epistles of Longinus and Augustus, 2. the Testimony of Ursinus, 3. and the two-part Dialogue of Patrophilus and Ursinus. They were published (in part) as appendices to Ignatius Rahmani’s edition of the Syriac Acts of Pilate in 1908. They are excerpted also in a number of other texts: the Chronicum maroniticum, Theodore Bar Konai’s Liber Scholiorum, the Chronography of Bar Hebraeus, Solomon of Basra’s Book of the Bee, the Chronicle of Michael the Syrian, and in Arabic in Agapius of Hierapolis’ Kitav al-‘unvan. Part way through working on the material, I came across Yury Arzhanov’s Syriac Sayings of Greek Philosophers (Peeters, 2019), which includes an edition of the complete text from which Rahmani excerpted the testimonia. My contribution to the study of this material is the mention of several additional manuscripts of the Sayings of Greek Philosophers and the placing of the testimonia into the broader phenomenon of having so-called “pagan” philosophers acknowledge the life and activities of Jesus and other early Christian figures. The most well-known example of this literature is the Epistles of Paul and Seneca, but I added also several testimonia appended to the Epistles of Pilate and Herod and the Testimonium Longinus. The latter text is a list of Greek rhetoricians, including Paul, attributed to Cassius Longinus, a third-century rhetorician and philosopher; the text is found in three Greek gospels manuscripts. The testimonia will be included in MNTA 3; in the meantime, information about the texts can be found on e-Clavis (HERE and HERE).

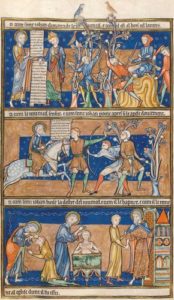

Finally, Jacob A. Lollar (Abilene Christian University) finished the session with “‘Listen to a Story, That Is Not a Story…’: Eusebius, John the Son of Zebedee, and John and the Robber in the Syriac Tradition.” As mentioned earlier, John and the Robber, a story about the apostle told by Clement of Alexandria (and after him by Eusebius of Caesarea), was included in MNTA 1 by Rick Brannan, who also has compiled an e-Clavis page on the text. The story also gets detached from Clement or Eusebius and circulates in Latin in the Virtutes Iohannis and, as Lollar showed, in a manuscript of the Syriac History of John. A depiction of the story also appears in images of John’s life in the Trinity Apocalypse manuscript. The story occupies a place between scripture and apocrypha: Clement calls it a logos, not a mythos (it’s true). The phenomenon is similar to the Abgar Correspondence, which is lent authority by its transmission by Eusebius. Lollar sees the story, and other freely circulating stories about the apostles, like episodes in a television show, each of which can be enjoyed on their own. He urged also that we move beyond using such orphan stories to reconstruct larger works and appreciate them as what they are, a position also advocated by Janet Spittler at last year’s SBL for the Vienna manuscript of “An Amazing Narrative” of John that has been characterized in the past as a fragment of the Acts of John (placed as chs. 87–105) but is an independent narrative that may not have been part of the early Acts. You can read Spittler’s paper in Ancient Jew Review.

Sessions over for the day, Stephen Hopkins, Bradley Rice, and I headed off for drinks and appetizers before making the 30 minute hike to the University of Virginia reception on the Star of India, an iron-hulled sailing ship built in 1863, now a floating musum. We were invited by Janet Spittler, whose enthusiasm for the fact that “It’s on a boat!” could not be denied. It certainly was a great venue and it was enjoyable to chat with a number of apocrypha people around a large table that we had commandeered below deck. But all good things must come to an end, and five or six of us decided to move on to the University of Chicago reception at the Hyatt. Two cars were called, one by Janet and the other by a UC grad student who will not be named. As we waited, I felt the need to go to “the head.” Unfortunately, it’s an old boat with only one washroom. By the time I returned everyone was gone. Tears streaming down my face, I ran back to the Hyatt to catch up. They seemed quite surprised to see me—I am hard to shake. Apparently, it was said that “Tony’s an adult, he’ll be fine.” Not adult enough to hold the contents of his bladder for a five-minute car ride! Anyway, I won’t soon forget this betrayal. As it turned out, the reception was too noisy and I had already had too much to drink, so I headed back to my room and called it a night.

Up next on day three: planning the 2020 NASSCAL conference, the Wipf & Stock reception, and finding out its “safe” to offer me edibles on the street.