Finding Jesus Episode 3: The Gospel of Judas

This week’s episode of CNN’s six-part documentary series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery focused on a literary artifact: the Gospel of Judas. When the text was published in 2006 it caused quite a sensation. It’s initial editors declared that it portrayed Judas as a hero, not a villain. Scholars were cautious in their conclusions about the text, saying that it had no bearing on the historical Judas, but the media were not interested in what it revealed of second-century controversies—they wanted to know what it said about the life of Jesus.

This week’s episode of CNN’s six-part documentary series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery focused on a literary artifact: the Gospel of Judas. When the text was published in 2006 it caused quite a sensation. It’s initial editors declared that it portrayed Judas as a hero, not a villain. Scholars were cautious in their conclusions about the text, saying that it had no bearing on the historical Judas, but the media were not interested in what it revealed of second-century controversies—they wanted to know what it said about the life of Jesus.

The first half of the episode focuses on dramatizing the relationship between Jesus and Judas. Certainly he was one of the Twelve, the inner circle of Jesus’ followers, but perhaps producers went a bit too far in portraying the two men as intimate friends. Ben Witherington says, “Judas may well have been one of the very first he recruited”—sure, but we have no evidence of that. Other contributors declare Jesus and Judas close friends and state that Jesus was an excellent judge of character (I think the writer of the Gospel of Mark would disagree); one dramatization shows Jesus saving Judas from a fall.

The scene changes to the story of the woman who anoints Jesus. The producers focuse on the version of the tale from the Gospel of John (12:1-11), where Mary, the sister of Lazarus, is identified as the woman with the jar and Judas objects to the wasting of the expensive perfume. The story is much different in the Synoptics (Mark 14:3-9 par.), where the apostles gather at the house of Simon the leper, not Lazarus, and where both the woman and her apostolic adversary are unnamed. Unfortunately, the producers do not stay with John for the remainder of their telling of the arrest of Jesus; they incorporate Luke’s sweating blood (Luke 22:44), widely held to be a late interpolation into the text, and the identification of Jesus by the kiss of Judas, found only in the Synoptics (Mark 14:44-45 par.). Certainly any story of the betrayal has to include Judas’ kiss but, as I have said before, harmonization of the gospels should be avoided and the difficulties using them acknowledged.

The contributors spend some time questioning Judas’ motives. They suggest that Judas had become impatient, wanting to push Jesus into conflict with the Romans, or that he had become disenchanted due to Jesus’ pacifism. However, none of these explanations account for why Judas would accept money for the betrayal, if indeed that element of the story is true.

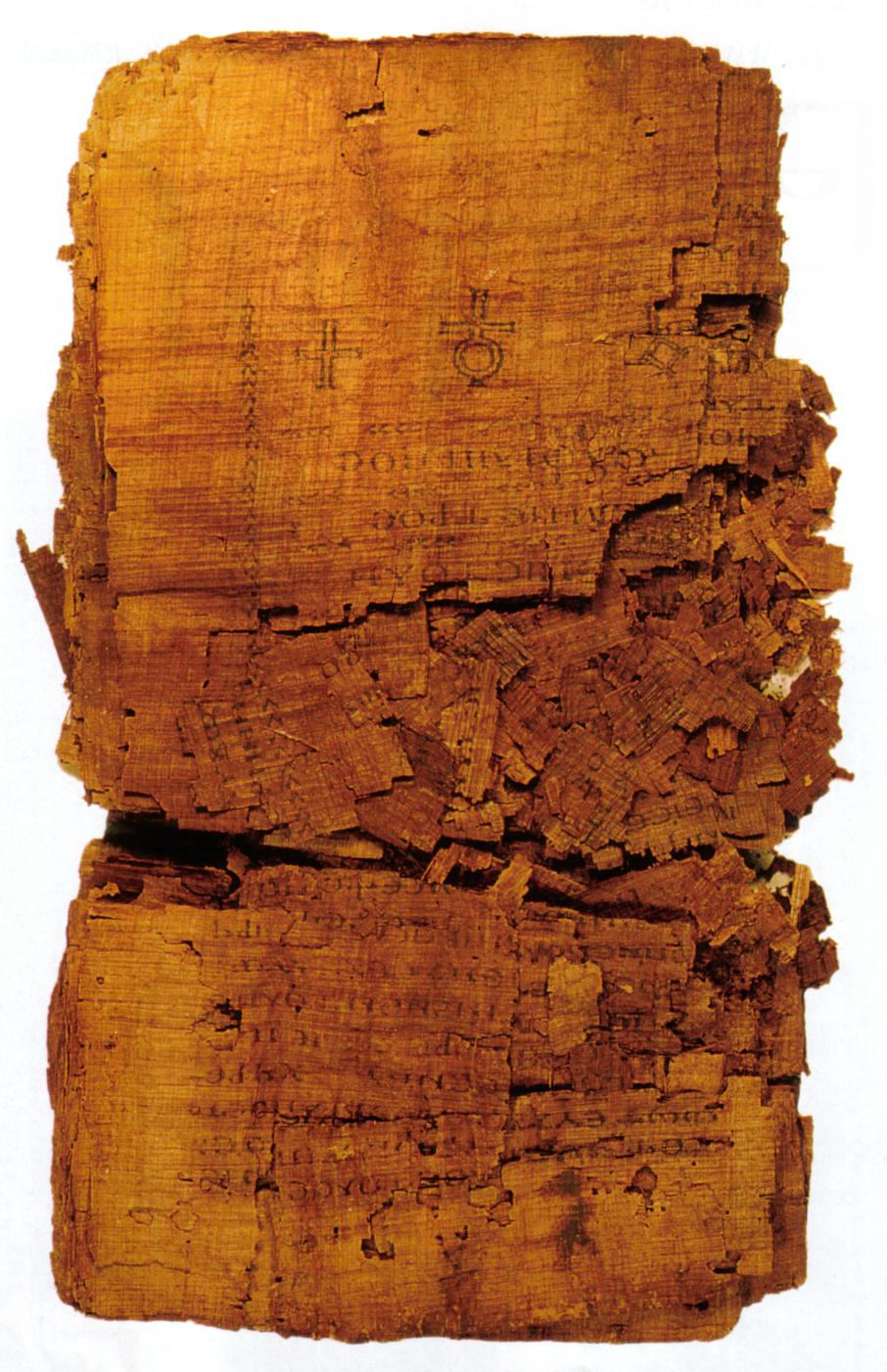

At this point, the publishing of the Gospel of Judas is brought into the story. Stephen Emmel appears, telling of his failed attempt to purchase the manuscript in 1983. We then hear of the roles played by Bruce Fellini and Frieda Tchacos, but nothing is said of the National Geographic Society and how their efforts to restrict access to the text led to the mistakes made in the first reconstruction and translation of the text. If other scholars were brought in as referees, the argument goes, then the editio princeps would have been much less flawed. It would have been helpful also to have mentioned at this point how Irenaeus and Epiphanius affected the NGS editorial team’s reading of the text. These heresy hunters (mistakenly, it seems) believed that those who valued the text saw Judas as a hero. When faced with difficult passages in the manuscript, the NGS team opted for readings that supported this view.

And this view is the focus of the initial discussion of the text in the episode. Elaine Pagels, Mark Goodacre, and Candida Moss all appear to agree that the gospel portrays Judas as a hero. Little is said of the remainder of the text; Goodacre does say that the Jesus of the text is mysterious and speaks in riddles that only Judas understands, but the viewers would get no sense of the Sethian elements of the text—probably a wise move given how difficult they can be to follow. The narrator concludes the segment saying that the Gospel of Judas “appears to give a new explanation” for Judas’ betrayal. The word “appears” was carefully chosen as the next segment demonstrates that the gospel does not portray Judas as a hero after all.

Shortly after the publication of the editio princeps two scholars working independently came to the conclusion that the NGS team’s reading of the text was wrong. April DeConick, included in the episode, gets much of the attention for this realization, but Louis Painchaud also deserves credit. Back in 2006, Louis presented his criticism of the NGS text at the Ottawa Christian Apocrypha workshop convened by Pierluigi Piovanelli; he published his findings in French as “À Propos de la (re)découverte de l’Évangile de Judas” in LTP 62.3 (2006): 553–68 and an English translation will appear later this year in a volume I co-edited with Pierluigi. I remember well the excitement in the room when Louis shared his own readings of the erroneous passages. One of these is mention by DeConick in the documentary—the NGS team translated the word daimone as spirit but, DeConick rightly says, “he is not a hero, he’s a fallen angel, a demon.”

Several new pieces of the text held back by Ferrini were published in 2008, and these helped to confirm DeConick and Painchaud’s positions. Geoffrey Smith, a contributor to the More New Testament Apocrypha volumes, appears in the episode to describe the contents of these fragments. Moss and Goodacre are then brought back into the discussion and are shown to be in agreement with the new position after all. Moss says, “the headline should have been that none of the apostles in the text are good.” Her statement made a useful segué into the gospel’s real value: as a criticism of proto-orthodox Christianity.

The final segment of the episode returns to the New Testament for its portrayal of the death of Judas. The narrator states that only one gospel (Matthew) says how the story ends and then follows a dramatization of Judas hanging himself. Surprisingly, nothing is said of the story of Judas’ death from Acts (1:18-20). There is a third account of Judas’ death narrated by Papias of Hierapolis (ca. 60-140 CE) and included, in a new translation by (coincidentally enough) Geoffrey Smith, in MNTA vol. 1. There are two versions of this account preserved by Apollinaris of Laodicea; the longer of the two states,

Judas walked about in this world as a weighty example of impiety. He was so inflamed in the flesh that he could not pass where a wagon could easily pass, in fact not even the bulk of his head alone could pass. For they say that the lids of his eyes were so swollen that neither could he see any light at all, nor could a doctor aided by instruments see his eyes. Such was their depth from the outer surface of his body. His genitals appeared to be more nauseating and enlarged than any other genitalia, and he passed through them pus and even worms that converged from throughout his body, causing an outrage on account of a simple necessity of life. After many tortures and punishments, they say, he died in his own land. His land remains until now desolate and uninhabited on account of the stench. Even to this day no one can travel through that place without holding their nose. So great was the judgment that spread through his flesh upon the earth. (trans. Smith).

Despite my minor criticisms, the episode is an excellent, succinct, and informative presentation of the Gospel of Judas. It avoids the temptation of arguing that the text says anything about the historical Judas but ends with some thoughts about how Judas must have been conflicted and that it is simplistic to think of him purely as a monster. I look forward to seeing what my Gnosticism class think of the documentary when I show it in class in a few weeks.