Anchor Bible Report 17: James the Less

It is Reading Week here in Canada, which means a break from teaching and a chance to get back to some (albeit very little) writing. I managed to finish off a section of my Anchor Bible project on apocrypha related to James the Less.

Besides the well-known apostle James, son of Zebedee (often called James the Great or Elder), three other men by the name of James appear in the New Testament Gospels: 1. James, son of Alphaeus, who is listed as one of the Twelve in all three Synoptics, 2. James the Less or Younger, who is said to be the son of Mary (not the Virgin, but identified, via John 19:25, as Mary, wife of Clopas and cousin to the Virgin Mary) and brother to Joseph/Joses (Matt 27:56; Mark 15:40), and 3. James the Righteous/Just, brother of Jesus. Often these three figures are conflated, so James Alphaeus’s place among the apostles is frequently supplanted by Jesus’ brother, despite the apparent lack of interest in Jesus’ ministry shown by him and his brothers in the canonical Gospels. Outside of the Gospels, James the Just appears also in Acts, Galatians (in both described as the “brother of the Lord”), and as the author of an epistle (calling himself “a servant of God and of Jesus Christ”). Because of the confusion of the Jameses, there are very few apocryphal texts and traditions about the son of Alphaeus. James the Just fares better, but much of what is said about him derives from Hegesippus by way of Eusebius.

Hegesippus (ca. 110–ca. 180) writes in his Commentaries on the Acts of the Church (quoted in Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 2.23.4-6; trans. McGiffert, NPNF):

James, the Lord’s brother, succeeds to the government of the Church, in conjunction with the apostles. He has been universally called the Just, from the days of the Lord down to the present time. For many bore the name of James; but this one was holy from his mother’s womb. He drank no wine or other intoxicating liquor, nor did he eat flesh; no razor came upon his head; he did not anoint himself with oil, nor make use of the bath. He alone was permitted to enter the holy place: for he did not wear any woollen garment, but fine linen only. He alone, I say, was wont to go into the temple: and he used to be found kneeling on his knees, begging forgiveness for the people-so that the skin of his knees became horny like that of a camel’s, by reason of his constantly bending the knee in adoration to God, and begging forgiveness for the people.

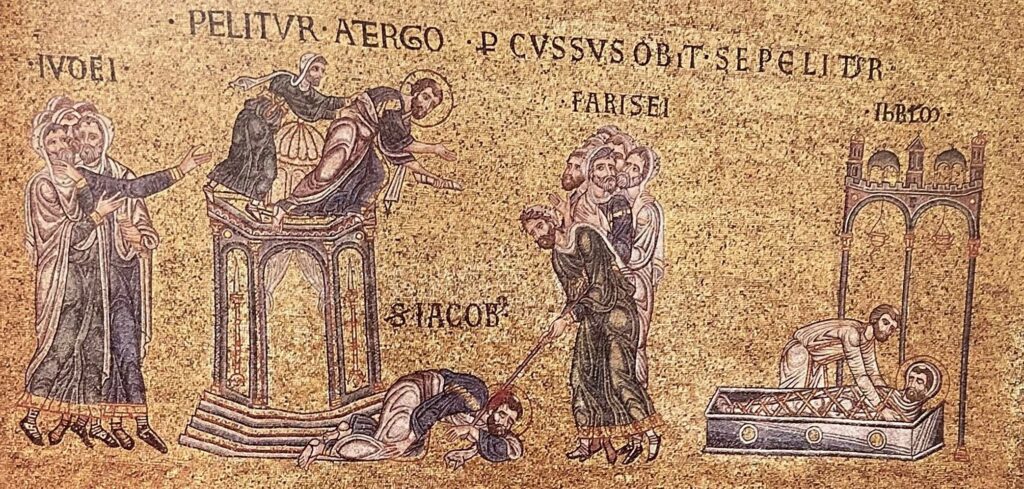

Then follows an account of James’s martyrdom (Hist. eccl. 2.23.8–18). According to Hegesippus, members of the “seven sects” challenged James about Jesus. His success in convincing them about Jesus’ divinity raised concern amongst the leaders in Jerusalem, so they asked James to go up to the pinnacle of the temple at Passover and tell the people Jesus was merely human. Instead, James declared that Jesus is the Son of Mon, who will come upon the clouds of heaven. Angered, the Jewish leaders threw James from the pinnacle and stoned him. James got to his knees and asked God to forgive his abusers, but he died after a blow to the head by a fuller (someone who beats clothes). James was buried on the spot. Finally, it is said that the siege of Jerusalem by Vespasian was God’s punishment for the murder of James. Josephus also mentions the death of James (Ant. 20.20; repeated in Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 2.23.20–24). He says the high priest Ananus brought James and others before the Sanhedrin on the accusation that they were “breakers of the law” and had them stoned. This was not supported by some, so King Agrippa removed Ananus from the priesthood. Clement of Alexandria (Hypotyposes 6–7; via Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 2.1.3–4) reports some of the same details as Hegesippus about the death of James (that he was thrown from the pinnacle of the temple and beaten to death by a fuller); he mentions also that James was chosen as first bishop of Jerusalem by Peter and the sons of Zebedee. Finally, Epiphanius adds another detail: James died a virgin at the age of ninety-six (Pan. 78.13.2)

With such information about the life and death of James so close at hand, there was little need for the creation of apocryphal accounts of his ministry and final days. Two Greek texts—cataloged as CANT 274/BHG 763y and BHG 763z—are merely excerpts from Eusebius. The Encomium on James by Andrew of Crete (BHG 766) and the derivative Hypomnema on James by Symeon Metaphrastes also use Eusebius but preface the martyrdom with discussions of the canonical Epistle of James. The Latin Passion of James, which circulated in the Apostolic Histories collection, again uses Eusebius but also integrates another source. This is an account found in the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions, though taken from the Latin translation by Rufinus. The story begins, like Hegesippus, with James debating several Jewish groups (Sadducees, Samaritans, and the scribes and Pharisees) in Jerusalem on Passover. He is joined by the apostles who have returned to the city for the festival and there they tell James about their various travels. For seven days, the apostles preach about Jesus and invite people to be baptized. Then a “hostile man” comes forward, accusing Jesus of being a magician and urging the crowds to kill the apostles. A riot erupts and the man throws James from the top of the temple stairs. James does not die, but his foot is permanently damaged. In a cliff-hanger ending, the man who attacked James is identified as Saul, who will one day be Paul, apostle to the gentiles.

An Armenian Martyrdom of James also draws on Eusebius but prefaces the account with some information about the various ways that James is a brother of Jesus: kinship through the tribe of Judah through David, kinship through the relationship between their mothers (James is the son of Mary’s aunt who is identified here as the Mary who was mother to James the Less and Joses), they were milk-brothers (the mother of James nursed Jesus), and they were alike in “size, bearing, and gesture” (these last two seem to be unique in Armenian tradition). The author states also that Jesus spent his first year of life in the house of James’ mother, which would mean Joseph was married to two women at the same time; however, the text never calls Joseph Mary’s husband, suggesting that he was merely her guardian. Furthermore, it states (in agreement with Clement of Alexandria) that Peter appointed him bishop of Jerusalem (a position he held for 30 years), and that he sent out both the 12 and the 70 on their preaching journeys.

The only texts that provide substantially new information about James are the Preaching and Martyrdom of James included in the Egyptian corpus of apocryphal acts. Portions of these texts are extant in their original Coptic form, but complete versions are available in Arabic and Ethiopic. The Preaching begins with the post-resurrection commissioning of the apostles; James is assigned to preach in Jerusalem “and in all its district.” From here the text unfolds by following many of the common motifs in the Egyptian acts, including Peter accompanying the text’s main protagonist to the city, initial preaching success leading to efforts by the authorities to kill the apostle, a brief stay at the home of a supporter (who later becomes bishop) outside the city, additional converts made through miracles and healings, the establishment of a church, and then the apostle’s departure. The Martyrdom begins with James in Jerusalem where he performs miracles and healings and becomes bishop. But he runs afoul of Ananus, the prefect of the city, who is described as a great lover of money. He and his wife Theopist? are having difficulty conceiving. But the pious Theopist? comes to James for help and he promises her she will have a child if she believes in Christ. She gives birth to a boy and in gratitude, names him James. When her husband finds out about her dealings with James, he gathers the nobles and accuses James of leading the people astray with his preaching. At this point the author integrates the material provided by Eusebius.

James the Just appears also in several texts from Nag Hammadi, including the Apocryphon of James and two texts called the Revelation of James. The first of these culminates in a new account of James’ martyrdom (he is arrested in error and stoned), and the second uses the same story told by Hegesippus but with some added details: after his fall from the pinnacle, the Jewish priests place a rock on his abdomen and trample on it, and then they make him dig a hole, bury him in it up to his abdomen, and stone him to death. Other significant traditions about James appear in the Gospel of the Hebrews (via Jerome) and the Gospel of Thomas (log. 12). Finally, there are also a few apocryphal epistles: the Letter of James to Quadratus (in which James requests information about Tiberius Caesar’s plans to punish the Jews for the death of Jesus; a new translation of this text is included in MNTA 3), and a response to a letter from Peter included together in the opening texts of the Pseudo-Clementines.

As for James, the son of Alphaeus, far less is known about his exploits and martyrdom because he rarely appears as a character distinct from James the Just. There is a Greek martyrdom account (BHG 762z) extant in two manuscripts, but this text has not yet been published. Perhaps it is related in some way to the source used by Nicetas the Paphlagonian for his Encomium on James. Much of this text simply heaps praise upon James and is so nonspecific in its details that the subject could be any apostle. But Nicetas does say that James operated in Eleutheropolis, Gaza, and Tyre, and died by crucifixion in Ostracine (Egypt). The same information is given a few centuries later by Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos (Historia ecclesiastica 2.40), likely via Nicetas. A more significant parallel is found in the List of the Apostles and Disciples attributed to Dorotheus of Tyre. This list, composed likely before the time of Nicetas, includes the same combination of cities and the same details of martyrdom but assigns them all to a different apostle: “Simon, who was called Judas.” Likely this is an error, and James Alphaeus, the only apostle missing from the list, is intended.

The final, and most fulsome, text associated with James, son of Alphaeus, is the Martyrdom account included in the Egyptian corpus of apocryphal acts. The one known Coptic manuscript of the text has not been published, so the following summary depends on the Arabic text. James is identified at the start as both son of Alphaeus and brother of Matthew (since Levi, aka Matthew, is called “son of Alphaeus” in Mark 2:14). In the text, James comes to Jerusalem to preach in the temple. There he recounts basic points of orthodox doctrine—Jesus’ pre-existence with God, his incarnation and birth, and then death and resurrection. This angers the assembly, so they seize him and bring him before the emperor Claudius—an unlikely scenario since rule of Judea would have been administered either by a procurator or the king (Agrippa I or II). False witnesses come forward claiming James hinders people from obeying the emperor. The emperor sentences James to be stoned to death and the Jews carry out the order. He is buried beside the temple in Jerusalem on 10 Amsh?r (February 4 Julian), his feast day in the Coptic and Ethiopian Churches. Several features of the story are similar to the martyrdom of James the Just (the location in Jerusalem, death at the hands of “the Jews,” and burial beside the temple); it is possible that they derive ultimately from the List of the Apostles (Anonymous I), which seems to have influenced at least one other Coptic martyrdom account (the Martyrdom of Andrew). The list states, “James, son of Alphaeus, called the Just, was stoned by the Jews in Jerusalem and is buried there near the temple.”

One of the lingering questions about the James the Just traditions is to what extent are they to be considered “apocryphal”? The widely-dispersed martyrdom account derives from Hegesippus and thus carries a sense of history, though there is no guarantee that Hegisippus’s account is indeed historical. Nevertheless, its inclusion in Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History has helped to lend it authenticity, or at least orthodoxy. A similar situation exists for the Abgar/Jesus Correspondence and, to a lesser extent, the stories of John and the Robber (told by Clement of Alexandria, Quis dives salvetuer 42.1–15) and John and Cerinthus (told by Irenaeus, Adversus haereses 3.3.4). These examples begin as apocryphal texts/traditions, are taken up by orthodox writers as if genuine, and then they are incorporated again into apocryphal texts (the Abgar/Jesus Correspondence forms the basis of the Doctrine of Addai, the Acts of Thaddaeus, and the Story of the Image of Edessa; John and the Robber appears in the Latin Acts of John and some manuscripts of the Syriac History of John; John and Cerinthus, however, at least to my knowledge, does not appear in any apocryphal text). These kinds of transformations illustrate once again the porosity of the boundaries between the traditional categories of Christian literature.

For bibliography, consult the entries for the texts on e-Clavis.

Nice to know anither Canadian is seeking out truth.

Any luck with Mary Magdalene?

Lisa

Sister in Christ

Ontario Canada

Hi Lisa,

I will get to the Mary Magdalene materials soon enough (and hopefully will find time to put together a blog post on them). I’m not sure I’m finding any “truth,” mind you.

t.

Hi Tony: James ‘the Righteous’

John 21(1-8): After these things Jesus shewed himself again [the third time] to the disciples at the sea of Tiberias; and on this wise shewed he himself. There were together Simon Peter, and Thomas called Didymus, and Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, and the sons of Zebedee [James ‘the Righteous’ and Matthew were given in the Gospel of Thomas], and two other of his disciples [Nicodemus the author and Lazarus the disciple whom Jesus loved]. Simon Peter saith unto them, I go a fishing. They say unto him, We also go with thee. They [7] went forth, and entered into a ship immediately; and that night they caught nothing. But when the morning was now come, Jesus [Lord Eve/Jesus the Son/Mother] stood on the shore: but the disciples knew not that it was Jesus. Then Jesus [Eve the Mother of all living] saith unto them, Children, have ye any meat? They answered him, No. And he [she] said unto them, Cast the net on the right side of the ship, and ye shall find. They cast therefore, and now they were not able to draw it for the multitude of fishes. Therefore that disciple [Lazarus – ‘the man old in days’] whom Jesus loved saith unto Peter, it is the Lord [Eve/Jesus the Son/Mother]]. Now when Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he girt his fisher’s coat unto him, (for he was naked,) and did cast himself into the sea. And the other disciples [4 – Andrew, Philip, Joseph the father of Jesus and Judas not Iscariot] came in a little ship; (for they were not far from land, but as it were two hundred cubits,) dragging the net with fishes. [Note: ‘for every woman who makes herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven’ & ‘the kingdom of the Father is like a man’ & ‘the kingdom of the Father is like a woman’ – Do you now understand?]

Nicodemus is the author of the Gospel of John and the Gospel of Thomas which I used to recreate his John + Thomas. Today it has exposed all the lies which Christianity was built upon. The time has come for the people to know the truth for without it they can not leave this world.