Anchor Bible Report 16: The Acts of Philip

I have spent the past three weeks or so compiling information on the various traditions about the apostle Philip. The main one of course is the Acts of Philip, but there are also texts in Coptic (and from this Arabic and Ethiopic), Latin, and Irish. They will lead off my chapter on “other” apocryphal acts—that is, not the five “great” acts (Andrew, John, Peter, Paul, and Thomas) and related texts. This decision is based mostly on issues of space: the chapter on the big five is already really too long. But placing Philip in this “other” chapter is really a disservice to Acts Phil.

The text has been championed by only a few previous scholars—chiefly François Bovon and Christopher Matthews. M. R. James (1924: 438–39) early on declared that Acts Phil. belongs to the “secondary” stage of development of the apocryphal acts because it borrows material from the earlier texts, including part of the hymn material from the Acts of John and the Peter’s speech from the cross from the Acts of Peter. But Acts Phil. is still pretty early, likely composed not long after the others (fourth century but drawing upon material from the third). The diminishing of its importance has resulted in its virtual exclusion from Christian apocrypha collections, or at least the English compendia, which only present portions or summaries. But don’t despair, English readers can find it in the affordable translation by Bovon and Matthews (2012). And it’s worth seeking out, because this text does have a lot to offer.

As with the other early acts (except the Acts of Thomas), Acts Phil. requires some reconstruction. Unfortunately, the descriptions of manuscripts given in the scholarship are not easy to follow. I have been relying on Bovon’s comprehensive 1988 essay for this information, because I don’t yet have access to his subsequent critical edition (with Amsler and Bouvier in 1996). I’m hoping the edition will clear up some lingering questions. Another fabulous resource is Bovon’s essay on “Editing the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles” (1999), which reveals how he found the manuscripts to create his edition (and in the process provides valuable lessons on the particularities of establishing critical editions for apocryphal texts). Bovon’s greatest achievement for the study of Acts Phil. was the discovery of the manuscript Xenoph?ntos 32, which contains almost the entirety of the text (pages from acts 2, the beginning of 8 to the first part of 11, and a portion of 15 are absent due to damage, and act 14 ends abruptly). Several other manuscripts provide some of these missing sections, leaving mostly 9 and 10 unrecovered.

Even in its near-complete form, the text seems to be a compilation of materials, with the units comprising: act 1, act 2 (drawing on material from act 6 and the martyrdom), acts 3–4 (a transformation of material from canonical Acts 8 on the evangelist Philip), acts 5–7, and acts 8 through to the martyrdom. The latter portion, considered to be the oldest, features Philip, his sister Mariamne, and Bartholomew. They are instructed by Jesus to evangelize Opheorymos, which means “Promenade of the Serpents” and is later identified as Hierapolis. There they will free people from the worship of the Viper, the mother of the serpents—evoking here the goddess Cybele, whose cult originated in the area (Phrygia). They are accompanied on their journey by two talking animals: a leopard and a young goat—two animals associated also with Cybele. Philip and Mariamne operate as a unit and sometimes their activities fall along gender lines (she baptizes the women and Philip baptizes the men), at others they cross gender boundaries: she is praised for her masculine bravery while Philip is criticized for his “womanly” cowardice. Like other apocryphal acts, the text champions asceticism—not only advocating abstinence but also austere dress, and avoidance of wine. Early scholarship on the text placed it among heretical groups located in Phrygia—whether Encratites, Montanists, or Apotactics—but the precise theological allegiance of its author is not particularly important, or recoverable for that matter (on such theories, see Slater 1999: 297–304). And the elements of their practices that we would expect to be objectionable to orthodoxy are nevertheless retained in the sources that come down to us (I mean, if the text was that bad, why do we still have it at all?).

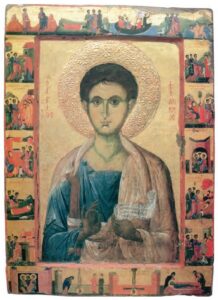

One of those sources is not a manuscript at all but an icon (for images see Bovon 2009 and the Materiae apocryphorum page on e-Clavis). It can be found at a church dedicated to Philip in Arsos, Cyprus; this same church claims to have a relic of Philip (his head) and stands next to a church dedicated to Mariamne. The icon features a central image of Philip surrounded by 18 vignettes based on stories from Acts Phil. These stories have been adapted to some degree—episodes from early in the text that feature Philip here include the full cast of characters (Philip, Mariamne, Bartholomew, and the two animals)—but what is important is that the thirteenth-century artist knew the full text and seemed to have few concerns about its content (though of course there is only so much information you can present in an image).

Another mystery about the contents of the original text is elicited by several manuscripts of the martyrdom that tells the story of the translation of Philip’s body from Opheorymos to Hierapolis (presented here as two distinct locations). This portion of the martyrdom was published separately by M. R. James (1893: 161–63) because Tischendorf, who earlier published the martyrdom from the same manuscript (1866: 141–56), did not think it original to the text. Bovon, however, believing that originally Acts Phil. set the martyrdom in the fictional land of Opheorymos, thinks this epilogue may be the true ending of the text (though I suspect not, since the indictments of the cult of Hierapolis are pretty clear). Hierapolis was certainly early associated with Philip. It is said to be the place of burial both for Philip and his daughters by Papias and others. And in 2011 archaeologist Francesco D’Andria found the tomb of Philip in a fifth-century complex of buildings that included a church and martyrion (discussion in D’Andria 2017; and Wilson 2022). A sixth/seventh-century bread stamp from the site is also extant—it features an image of Philip in front of the two buildings (for more information, see the Materiae apocryphorum page).

Bovon’s 1988 essay lists also the various Greek adaptations of the text, which includes summaries and epitomes in various menologia and synaxaria, and transformations by Nicetas of Paphlagonia and Symeon Metaphrastes. These have not yet been translated into English (nor yet added to the e-Clavis), but Bovon reports that they essentially summarize the text, eliminating some of the wilder elements, such as the baptism of the animals.

The sources for Acts Phil. are primarily Greek; only the martyrdom appears in early translations (Armenian and Georgian). Other languages (Coptic-Arabic-Ethiopic, Latin-Irish, Syriac) have their own traditions that have very little connection to the early acts. One of these is the Ever-New Tongue, known primarily through the work of John Carey (2009 and several previous studies). This Irish text features a delegation of Jewish sages on Mount Zion who engage in a dialogue with an apparition of Philip. The dialogue is about the creation of the cosmos, and Philip’s responses to the sages’ questions are expansions of Genesis 1. Carey compares the text to Coptic revelatory dialogues, such as the Investiture of the Archangel Michael, in which Jesus appears and answers questions about the cosmos from his apostles. Since the text features a “risen” Philip, there is not much in the text that provides information about the apostle’s missionary journeys, but it does mention that the source of his name, the Ever-New Tongue, is because his tongue was cut out by his enemies nine times to prevent his preaching, but each time it grew back. A fuller version of this legend appears in the Irish translation of the Latin Acts of Philip.

Philip appears also in several other texts. In the Pistis Sophia he is said to be one of three witnesses to the life and teachings of Jesus (along with Matthew and Thomas) and engages Jesus in dialogue, and he appears prominently in Letter of Peter to Philip. The apostle appears also in a sequel of sorts to Acts Phil. called the Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae (see this previous post). The text opens with John coming to Hierapolis where he helps Philip cast out the Viper. Then the two journey on to Chairetopa where they announce to the people that the power of Michael would soon be manifest there. After they depart, a healing spring appeared in that place. It is surprising that apocryphal writers do so little with Philip’s daughters, who are mentioned in Acts 21:8–9 and by several patristic writers, including Papias, who claimed to know the women (see Eusebius, Eccl. hist. 3.39.4; 3.39.9). There are some traditions which provide their names—either Hermione, Eutychius, and Mariamne, or Charilene, Irais, and Eutychian—but I have yet to track these down.

As I worked through the Philip material, I was able to update the e-Clavis entry on Acts Phil. considerably, though I still wonder if some of the iterations of the text noted by Bovon (such as the Martyrdom manuscripts with the translation of Philip) should receive their own entries, and in light of these decisions, how best to present the information in my own work—which is longer already than it should be! (At the moment, the Philip texts take up 20 pages of the chapter). There is no danger in this volume, at least, that Acts Phil. will suffer its usual neglect.

Bibliography

Amsler, Frédéric, François Bovon, and Bertrand Bouvier. 1996. Actes de l’apôtre Philippe. Introduction, traductions et notes. Apocryphes 8. Turnhout: Brepols.

Bovon, François. 2009. “From Vermont to Cyprus: A New Witness of the Acts of Philip.” Apocrypha 20: 9–27.

__________. 1999. “Editing the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles.” Pages 1–35 in Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles. Edited by François Bovon, Ann Graham Brock, and Christopher R. Matthews. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions.

__________. 1988. “Les Actes de Philippe.” ANRW II.25.6: 4431–527.

Bovon, François and Christopher R. Matthews. 2012. The Acts of Philip: A New Translation. Waco, TX: Baylor.

Carey, John, ed. and trans. 2009. Apocrypha Hiberniae 2, Apocalyptica 1. In tenga bithnua: The Ever-New Tongue. CCSA 16. Turnhout: Brepols.

D’Andria, Franceso. 2017. “The Sanctuary of St. Philip in Hierapolis and the Tombs of Saints in Anatolian Cities.” Pages 4–18 in Life and Death in Asia Minor in Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Times. Edited by J. Rasmus Brandt, Erika Hagelberg, Gro Bjornstad, and Sven Ahrens. Studies in Funerary Archaeology 10. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow.

James, M. R. 1924. The Apocryphal New Testament: Being the Apocryphal Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Apocalypses. Oxford: Clarendon.

__________. 1893. Apocrypha Anecdota: A Collection of Thirteen Apocryphal Books and Fragments. Texts and Studies 2.3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matthews, Christopher R. 2002. Philip: Apostle and Evangelist. Configurations of a Tradition. NovTSup 105. Leiden: Brill.

Slater, Richard N. 1999. “An Inquiry into the Relationship between Community and Text: The Apocryphal Acts of Philip 1 and the Encratites of Asia Minor.” Pages in 281–306 in The Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles. Harvard Divinity School Studies. Religions of the World. Edited by F. Bovon, A. G. Brock, and C. R. Matthews. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tischendorf, Constantin. 1866. Apocalypses Apocryphae. Leipzig: Mendelssohn.

Wilson, Mark. 2022. “Philip in Text and Realia: Contextualizing a Biblical Figure Within Roman Hierapolis.” JECS 12.2: 73–101.