2022 SBL Diary: Part Two

My third day in Denver began early with a pilgrimage (of sorts) to Red Rocks Amphitheatre. To people of my age and musical interests, Red Rocks is famous as the recording site of U2’s career-breaking Under a Blood Red Sky EP and video. Plenty of other bands have played the venue also, some even willing to bring a larger show to this smaller theatre (aprox. 9500) just for the joy of playing in this stunning, and storied, location. I convinced two friends (and fellow U2 fans), Phil Harland and Bob Derrenbacker, to join me for the trek and we hailed an Uber to take us there. Once we arrived, we hauled our creaky bones up and down the flights of stairs, stood on the stage (if only I had brought an instrument; I could then say I played at Red Rocks!), and just soaked in the atmosphere. Bob even played a couple of U2 songs on his phone to capture the spirit of that seminal event. I think I even saw tears welling in Bob’s eyes. Quoting Nigel Tuffnell of Spinal Tap, I said, “It really puts perspective on things, though, doesn’t it?” On cue, Bob responded, “Too much. There’s too much fucking perspective now.”

With some Red Rocks merch in hand, we headed back to the conference centre for afternoon sessions. Jacob Lollar (Universität Regensburg) started the Apocryphal Acts session with “Canonizing Thekla: The Acts of Thekla and Her Legacy in the Syriac Tradition.” Lollar remarked that much work has been done on the veneration of Thecla in Egypt (by Stephen Davis and others), but the Syriac tradition has received far less attention. There are 12 Syriac manuscripts of the Acts of Thecla, which circulates in Syriac only as an independent text (there is no evidence for Acts Thecla and 3 Corinthians as part of the larger Acts of Paul in Syriac), typically in collections of texts about holy women. Only one of these manuscripts includes an epilogue bringing Thecla to Seleucia—a journey well-known in Greek sources, though in the Greek texts it is clear that the location is the Seleucia in Pamphylia. Lollar mentioned in his presentation another shrine to Thecla in Maaloula, Syria (Deir Mar Takla; information HERE). I asked Lollar how this location is justified in the tradition and he noted that there was another Seleucia in Syria (Seleucia in Pieria, modern Çevlik, though this location is almost 500 km away from Maaloula). Sources (such as the Homily on Saint Thecla the Martyr by Severus of Antioch) do mention a second shrine to Thecla in Antioch (a close neighbor to Seleucia in Pieria), but it is not clear from these sources whether this shrine was located in Syrian or Pisidian Antioch. Lollar noted also some particularities of the Syriac tradition, including softening the eroticism between Thecla and Paul (as well as never depicting the two alone) and the removal of Thecla’s title as “beast-fighter.”

Another Universität Regensburg resident (and Thecla enthusiast), Thomas Tops, spoke next on Thecla as “truth-teller” (a shift in focus from the original title of the paper: “A Social-Historical Study of Truth-Telling in the Acts of Andrew”). He began with a discussion of where and when it was appropriate in antiquity for women to display parresia (openness)—typically in the household but outside the home was possible for women of high social standing. Tops connected this cultural more to the story of Thecla’s encounter with the suitor Alexander in Antioch. Readers of the text, Tops said, would see her public challenge of Alexander as countercultural, and as chafing against the expectations of self-control outlined in 1 Timothy 3:11. Finally, Tops compared the story with the meeting of the Cynic Diogenes and Alexander the Great, which was widely known around the time of Acts Thecla’s composition.

The final paper of this short session was given by Michael Scott Robertson (Florida State University). In “Church and Empire in the Acts of Titus” Robertson noted how Titus, here elevated to the status of an “apostle,” has both ecclesiastical and imperial power—he is a descendant of Minos of Crete, he is the nephew of the local procurator, and succeeds where the emperor Trajan fails to build a temple (though Titus makes it a martyrion). Robertson argued that the text was composed at a time in the post-Constantinian empire when ecclesiastical and imperial power where in competition (or at least the relationship was contentious). In the question period, Tobias Nicklas asked whether the reader would understand that the text was wrestling with a late antique problem and not one of the first century (though really, all of our post-second century texts speak to issues of their own time, don’t they?).

At the end of the session I was introduced to Acacia Chan (University of Texas at Austin), whose paper—“Mary Sues and Rebellious Apostles: A Fan Fiction Theory Reading of the Acts of Matthias and Andrew”—I missed while I was meeting with my editor. Janet Spittler called it the best discussion of fan fiction she had ever heard. I seem to have become notorious for my dislike of the application of fan fiction methodology to apocryphal texts. Maybe Chan will change my mind.

Before we all headed off to other sessions, several of us huddled together for a short business meeting to plan next year’s sessions. One idea I volunteered was to have an invited panel to present translations of selections from the Hypomnemata of Symeon Metaphrastes. These tenth-century rewritings of apocryphal acts have never appeared in modern translations, nor in proper critical editions for that matter. Janet Spittler remarked that the papers could be collected for a publication (or maybe we could do a series of sessions over three years and cover the entire corpus).

My final session of the day was only tangentially related to Christian apocrypha. The Metacriticism of Biblical Scholarship section assembled a panel to discuss “Justice and Ethics in Citational Practices.” The panel included Mark Leuchter (Temple University), Catherine Bonesho (University of California-Los Angeles), Charles Schmidt (University of Houston), M Adryael Tong (Interdenominational Theological Center; paper available online HERE), and Eric Vanden Eykel (Ferrum College; paper available online HERE). The problem addressed at the session was what do to about citing the works of known sexual offenders, principally Jan Joosten and Richard Pervo (an earlier discussion of the issue can be viewed at the Urbs and Polis site). Pervo is well-known to Christian apocrypha scholars for his work on the Acts of Paul, and more widely as a proponent of the late dating of the canonical Acts. Both Schmidt and Eric Vanden Eykel spoke on their interactions with Pervo, which began well because he could be affable and supportive of young scholars. But when they learned about Pervo’s conviction for possession of images of sexual abuse of children, these relationships turned sour. I have my own story to tell regarding Pervo. He made two contributions to the MNTA project: the Acts of Titus for vol. 1 and the Acts of Nereus and Achilleus for vol. 2. I was not entirely comfortable working with Pervo, but tried to take my cues from colleagues who considered the right course of action (for them, at least) was to accept him back into the academy after serving his time. But today, as I write on apocryphal acts for the Anchor volume, I struggle with whether or not to cite his work. I have the same issue with Helmut Koester, whose work was far more influential on me. He has been accused of sexual assault by Elaine Pagels and was known by therapists at Harvard Health Services, Pagels says, as “Koester the Molester.” Strangely, I feel less conflicted about not citing his work—maybe because I feel more betrayed by him, maybe because I never met him, or maybe because he was never punished for his crimes. Maybe all three. The panelists presented several ideas about how to deal with the problem of citation, but I was particularly affected by Bonesho’s point that not citing at all (that is, without comment) means erasing the offense. I was pleased that the panel did not push an “orthodoxy” for how to deal with the issue, because I’m not sure there is a right answer and I don’t think it’s right to pressure people to conform to one. All of the panelists did agree that conversation about the issue must continue, and that has been my strategy with my students. Twice in recent years I have raised the issue of scholars behaving badly and brought into the discussion my collaborations with Pervo. If nothing else, students will see that we do not think criminal behavior is acceptable and they should feel supported if they experience harassment by any instructors or advisors. I finished the night with dinner with James McGrath (Butler University). We have been toying with putting together an edition and translation of apocryphal John the Baptist texts. He is working on a book about John, and has taken interest in an unpublished Greek text called the Life and Conduct of John the Baptist. For my part, I have a few texts in my pocket from MNTA for which I’d would like to find a home. But first, James has to finish his book. So we will see where this leads.

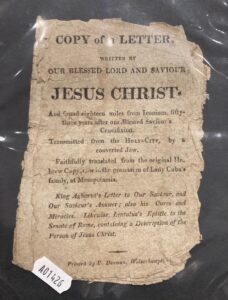

On the final morning of the conference, I met with fellow NASSCAL board members (and a friend or two) for a big sloppy breakfast at Sam’s No. 3 (which touts itself as “Denver’s Best Diner”). With full bellies, we waddled over to the conference center for the final Christian apocrypha session (in conjunction with Corpus Hellenisticum Novi Testamenti): “Please Recycle: Repetition among Apocryphal Traditions.” The first paper was by Janet Spittler: “Proper Nouns in the Letter of Jesus Christ That Fell from Heaven.” Other than, perhaps, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Letter has to be the most maligned of apocryphal texts; despite being very plentiful—in all languages you can imagine, except (weirdly) Coptic—the Letter is unattractive to many scholars because it’s the basest expression of popular piety: a chain letter. Spittler presented arguments for both Latin and Greek origin, favoring the former in sixth-century Spain or Gaul. Parallels in the Greek text to the Dormition of the Virgin by the Apostle John and to the Apocalypse of Anastasia are likely later additions. Most of Spittler’s talk focused on later (recycled) versions of the letter, specifically English and German versions that circulated in North America—she even brought along a few examples. One of these was from an American broadsheet and Spittler noted that sometimes these would be printed along with journalistic discussions of their legitimacy in light of contemporary (19th-century) discoveries of other apocrypha. One person even tried to copyright the text in 1868, which would have rendered it impossible for it to circulate (at least legally) as a chain letter.

Clare Rothschild (Lewis University) came next with “Early Christian Dynasty in the Apocrypha.” Her focus was on the recycling of motifs in apocryphal acts. “Individualism is flattened,” she remarked, when later acts depict the same activities as the apostles perform in earlier acts. The goal is to demonstrate a “genealogy of power” that continues over time. As an example, Rothschild discussed the final story of the Acts of Timothy, in which the apostle is clubbed by a mob of Dionysian revelers. His followers remove him from the melee, but soon after he breaths his last. Rothschild thinks this story could be a recycled near-death episode of John’s career, and presented images from three John cycles which seem to depict the same story for John. It’s a mysterious scene, because it has no basis in any known acts of John text.

The final paper of the session (and for me, the annual meeting) was by Tobias Nicklas (Universität Regensburg): “Recycling of Apocryphal Literature in Late Antiquity.” He discussed three apocryphal texts: Martyrdom of Mark (of which he contributed a new translation for MNTA 3), the Acts of Thomas, and the Life and Miracles of Thecla. He echoed some of the arguments I made in my SBL 2021 paper—namely, that the reasons for shortening and replacing earlier apocryphal acts may have less to do with offense at their contents and more to do with pragmatism, such as shortening the material for liturgical reading, and that perhaps scholars should focus more of their time on the most widely copied and used texts (such as the Acts of John by Prochorus, or the Hypomnemata of Symeon Metaphrastes) than the early apocryphal acts. Nicklas commented also that I am the best editor he’s ever had (aw, shucks), though what he really means is I made him do extra work. It’s a gift.

After some quick goodbyes, all that remained was for me to get to the airport for the flight home. As fellow Kitchener (Ontario) native Mona Tokarek LaFosse and I worked our way through the slow, labyrinthine line for security, I asked her “Is it all worth it?” The SBL meeting is an expensive endeavour and, again, my atrophied social skills and heightened anxiety issues made this year trickier than others. I am aware of how privileged I am to have a healthy expense account to draw from and to be able to afford my own hotel room, rather than curling up on a floor with four other people (but those were the days, eh?). By next year, things might be closer to “normal” in the world, and SBL might feel more like it used to. Still, I hope more can be done to expand access so that it is easier for everyone to participate. Next year in San Antonio!