“Canonical Apocrypha” in the Menologion of Symeon Metaphrastes

Maurice Geerard’s indispensable Clavis apocryphorum Novi Testamenti (CANT) includes mention of a number of works that are each described only as a “commentarius” (from the Greek hypomnema; on genres in hagiographical literature see Hinterberger 2014) by Symeon Metaphrastes. Little bibliographical information is provided for them—amounting, for the most part, to a reference from Migne’s Patrologia Graeca. The reason for this is simple: very little work has been done on the texts, many don’t even have proper critical editions, and only a few of them have been translated into a modern language. What are these texts? And what are their value for the study of Christian apocrypha?

Symeon Metaphrastes was a hagiographer of the late tenth century who was appointed by the emperor Basil II (976–1025) to construct a new, official menologion—that is, a collection of saints’ lives to be read on their designated feast days. Previous menologia existed but they varied from one another significantly, both in scope and selection of texts. But in Symeon’s time there was a movement toward standardization, begun a few centuries earlier with the creation of the Byzantine calendar of feast days and the subsequent destruction of all rival calendars. Some early scholars of hagiography accused Symeon of destroying earlier texts, but Symeon’s process was rather conservative. He took earlier texts, made stylistic improvements (a process called metaphrasis), and arranged them according to the new calendar date. Most of these earlier texts still exist and indeed, by comparing them to their new incarnations, it is possible to get a clear picture of Symeon’s redactional strategy. It actually coheres well with the description given by Michael Psellos, who composed an encomium on Symeon (BHG 1675)—essentially, Symeon worked with a team of scribes, rephrased and sometimes augmented the texts orally, and the team would take down his words in shorthand and later write them out in full. A few texts, however, seem to have been Symeon’s own creations.

All told the Metaphrastic Menologion comprises 148 texts spread out across the calendar year from September 1 to the end of August (detailed descriptions in Ehrhard 1938: 2:306 ff; Høgel 2002: 172–204; see also Høgel 2014; and Lipsius 1883: 1:184–87). The whole collection comprises ten volumes and would have been a major expense for the monasteries and churches who were able to purchase a copy. And many did; the collection was very popular, so popular that 700 manuscripts and more than 100 fragments of the Menologion survive today. But there are some peculiarities about the collection. For one, the texts have an uneven dispersion, with some months having one text for every day, but some having only a few. There is good reason to believe this is due to Symeon not completing the project, either because he fell out of favor with Basil or because he died with the work unfinished. The Metaphrastic Menologion was published, alongside Latin translations, in PG 114–116, but some texts are missing and some are included that do not belong to the original collection. Some texts also appear in the Acta Sanctorum and in the appendix to Vasilij Latšyev’s Menologii anonymi, Generally these editions are based on single manuscripts but, on the positive side, there appears to be little variation between the witnesses.

Only 18 of the 148 texts in the Metaphrastic Menologion are relevant for the study of Christian apocrypha:

Sept. 6: Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae (BHG 1284); principally important because its introduction features apocryphal stories of the apostles Philip and John (see the discussion on Apocryphicity); edition by Bonnet (1899).

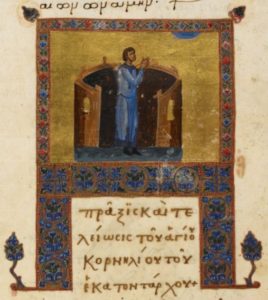

Sept. 13: Acts of Cornelius (BHG 371); edition PG 114: 1293–1312 based on Paris, BNF, gr. 1489; English translation by Tony Burke and Witold Witakowski in MNTA 1:337–61.

Sept. 24: Martyrdom of Thecla (BHG 1719); edition PG 115: 821–45 reproduced from Pantini (1608: 250–91).

Sept. 26: Hypomnema on John (BHG 919–919b = CANT 221); edition PG 116:684–705, reproduced from Donato (1532: 999–1008); description in Lipsius (1883: 1:365–66); draws on the Encomium on John by Nicetas the Paphlagonian (BHG 930).

Oct. 1: Martyrdom of Ananias (BHG 76); edition PG 114: 1001–1009 from Paris, BNF, gr. 1546; draws on the earlier Martyrdom of Ananias (BHG 75x–z).

Oct. 6: Hypomnema of Thomas (BHG 1835 = CANT 248); Latin text in PG 116: 559–66 (no Greek text available at time of publication); description in Lipsius (1883: 1:244–45); draws on earlier texts and traditions.

Oct. 16: Martyrdom of Longinus the Centurion (BHG 989); edition PG 115: 32–44 based on Paris, BNF, gr. 774; draws on the Martyrdom of Longinus, by Ps.-Hesychios of Jerusalem (BHG 988).

Oct. 18: Hypomnema on Luke (BHG 991 = CANT 290); edition PG 115: 1129–40 based on Paris, BNF, 1631; discussion in Lipsius (1884: 2.2:362–63); draws on the Passion of Artemius by John of Damascus (BHG 170–171c), the Encomium on Luke by Nicetas the Paphlagonian (BHG 993c), and others.

Oct. 23: Hypomnema of James, Brother of the Lord (BHG 764); edition PG 115: 200–17 reproduced from Acta Sanctorum Maii I (1680: 735–38), based on Reg. suecia 13 (present shelf number unidentified); discussion in Lipsius (1884: 2.2:249–50); draws on the Encomium on James, the Brother of the Lord, by Andrew of Crete (BHG 766).

Nov. 14: Hypomnema of Philip (BHG 1527 = CANT 251); edition PG 115: 188–97 reproduced from based Acta Sanctorum Maii I (1680: 733–35), based on Vatican, BAV, Vat. gr. 1798; also extant in Church Slavic); summary in Bovon (1988: 4444–45) and Lipsius (1884: 2.2:22–23); draws on the Encomium on Philip, by Nicetas the Paphlagonian (BHG 1530). description in Lipsius (1883: 244–45).

Nov. 16: Hypomnema on Matthew (BHG 1226 = CANT 271); edition PG 115: 813–20, based on Paris, BNF, gr. 1430 (sic.; perhaps gr. 1530); discussion in Lipsius (1884: 2.2:127–30); draws on the Encomium on Matthew, by Nicetas the Paphlagonian (BHG 1228).

Nov. 25: Pseudo-Clementine Romance, Metaphrastic Epitome (BHG 345–347 = CANT 209.7); edition in Dressel (1859).

Nov. 30: Hypomnema on Andrew (BHG 101 = CANT 234); edition du Saussay (1656: 309–28); description in Lipsius (1883: 1:584–85); draws on the Encomium on Andrew, by Nicetas the Paphlagonian (BHG 100 = CANT 228) and the Life of Andrew, by Epiphanius Monachus (BHG 102 = CANT 233).

Jan. 22: Hypomnema on Timothy (BHG 1848 = CANT 296); edition in PG 114: 761–63 based on Paris, BNF, gr. 1457; discussion in Lipsius (1884: 2.2:387–88); draws on Acts of Timothy (BHG 1847 = CANT 295).

June 29: Hypomnema on Peter and Paul (BHG 1493 = CANT 196); edition in Acta Sanctorum, Iunii V (1709: 411–24), based on an unidentified manuscript.

Aug. 15: Hypomnema on the Virgin (BHG 1047–48 = CANT 93); edition in Latšyev (1912: 346–83), based on three Moscow manuscripts, and portions published in PG 115: 529–50.

Aug. 16: Story of the Image of Edessa (BHG 793–795); edition in PG 113: 423–54 (reproducing Combefis 1644: 75–101) and von Dobschütz (1899), pp. pp. 38*–85*; English translation by Nathan Hardy in MNTA 3 (forthcoming); draws on a pre-Metaphrastic version (BHG 796) composed by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913–959).

Aug. 29: Hypomnema on John Baptist (BHG 835–37 = CANT 182); edition in Latšyev (1912: 384–408, based on three Moscow manuscripts.

How was the transmission of apocrypha affected by Symeon’s project? Certainly these 18 texts benefited from the wide dispersion of the collection, and several of them are particularly significant: there are no other known texts on Cornelius, nor any earlier versions of the texts on Peter and Paul, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist; and both the epitome of Ps.-Clement and the Story of the Image of Edessa are important for the transmission histories of those particular traditions. The other texts are simply the latest iterations of stories of the apostles and other figures that circulated as early as the second century. Even if little of the original apocryphal acts survive in these versions, the Metaphrastic Menologion is worthy of attention, not only because it reveals something of the interests of tenth-century Byzantine Christianity but because the popularity of Symeon’s collection made these versions virtually “canonical”—a circumstance that has implications for discussions of the problematic canonical/noncanonical divide.

As popular as the Metaphrastic Menologion was, it did not put an end to the transmission of other apocryphal texts. Numerous pre-Metraphrastic menologia manuscripts still exist, both pre-dating and post-dating Symeon (Ehrhard 1937: 1:349–701 lists 90 of them); and some manuscripts contain mixtures of both Metaphrastic and non-Metaphrastic texts—indeed, the incompleteness of the Menologion invited the addition of other texts to complete the calendar of feast days, though the process also worked in reverse, with Metaphrastic texts added to earlier menologia. Apocrypha also appear in other contexts: in manuscripts dedicated to particular apostles, or in miscellaneous codices alongside a variety of other texts. Take the Acts of John by Prochorus for example: extant in over 150 manuscripts, this text clearly thrived despite Symeon’s “canonizing” efforts.

Scholars’ interest in early texts and the earliest versions of texts leave neglected the later works by Symeon and his immediate predecessors like Nicetas the Paphlagonian. Were they not listed in CANT, they may escape Christian apocrypha scholars’ attention completely. But even so, the fact that most of these texts have not been formally edited or translated indicates that there is still much work to do, particularly given the direction in the field toward the study of apocrypha from all times and places.

Works cited

Bolland, Jean et al., eds. 1709. Acta Sanctorum, Iunii. Vol. 5. Antwerp: P. Jacobs, 1709. 3rd ed. Paris: V. Palmé, 1867.

____________. 1680. Acta Sanctorum, Maii. Vol. 1. Antwerp: P. Jacobs. 3rd ed. Paris: V. Palmé, 1866.

Bonnet, Max. 1899. “Naratio de miraculo a Michaele archangelo Chonis patrato,” AnBoll 8: 287–328.

Combefis, François. 1644. Originum rerumque Constantinopolitanarum manipulus. Paris: Siméon Piget.

Dobschütz, Ernst von. 1899. Christusbilder: Untersuchungen zur christlichen Legende. 3 vols. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

Donato, Benardino, ed. 1532. Expositiones antiquae … ex diuersis sanctorum patrum commentariis ab Oecumenio et Aretha collectae. Veronae: Apus Stephanum & fratres Sabios.

Dressel, Albert Rud., ed. 1859. Clementinorum Epitomae Duae. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

du Saussay, Andreas. 1656. Andreas frater Simonis seu de gloria S. Andreae apostoli libri XII. Paris: Lutetiae Parisiorum.

Ehrhard, Albert. 1937–1952. Uberlieferung und Bestand der hagiographischen und homiletischen Literatur der griechischen Kirche von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts. 3 vols. TU 50–52. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

Geerard, Maurice. 1992. Clavis apocryphorum Novi Testamenti. Corpus Christianorum. Turnhout: Brepols. (=CANT).

Hinterberger, Martin. 2014. “Byzantine Hagiography and its Literary Genres. Some Critical Observations.” Pages 25–60 in volume 2 of The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Edited by Stephanos Efthmiadis. 2 vols. London and New York: Routledge.

Høgel, Christian. 2014. “Symeon Metaphrastes and the Metaphrastic Movement.” Pages 181–96 in volume 2 of The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Edited by Stephanos Efthmiadis. 2 vols. London and New York: Routledge.

____________. 2002. Symeon Metaphrastes: Rewriting and Canonization. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Latšyev, Vasilij V. 1911–1912. Menologii anonymi byzantini saeculi X quae supersunt. 2 vols. St. Petersburg: Tipografija Imperatorskoj Akademii Nauk.

Migne, Jacques Paul. 1857–1886. Patrologiae cursus completus: Series graeca. 162 vols. Paris: Cerf (=PG).

Pantinus Tiletanus, Petrus (Peter Pantini). 1608. Basilii Seleuciae in Isauria episcopi De vita ac miraculis d. Theclae virginis martyris Iconiensis Libri Duo. Antwerp: Moretus.

Société des Bollandistes. 1909. Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca. Brussels: Société des Bollandistes (=BHG).

Thank you. A very useful and interesting post. Are you (or someone else in the field) keeping a list of apocryphal works in need of a new (or first) edition?

I have no official list (though I should probably make one).

In the Philippines, some self proclaimed “Liturgists” refused to recognize Disciples not mentioned in the Canonical Gospels. They are ignorant of Apocryphal Gospels. What is the stand of the Catholic Church on Acts of Nicodemus and other Non Apocryohal Gospels on Passion and Death of Our Lord. Thanks

As far s I am aware, all apocryphal texts are condemned in Catholicism, but the traditions contained within some of them are reflected in such doctrines as Jesus’ descent to hell (from the Gospel of Nicodemus) and Mary’s immaculate conception (from the Protevangelium of James). Images based on these (and other) texts are also part of iconography. But there is no explicit acknowledgement where these traditions come from.