Apocryphal Acts in Syriac Manuscripts

I would like to thank Jacob Lollar, J. Edward Walters, and Slavomir Céplö for looking over a draft of this post and making suggestions for improvement.

In my last post, back in December, I provided an overview of sources for the “Egyptian” collection of the apocryphal acts of the apostles—manuscripts in Coptic, Arabic, and Ge‘ez. A follow-up was promised, and I will get to that soon, but for now I am taking a detour with a discussion of apocryphal acts in Syriac. Both posts derive from ongoing work on my next major project: an introduction to Christian apocrypha for the Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library.

The number of texts and manuscripts for the Syriac apocryphal acts is significantly smaller than for the Egyptian corpus. The path of transmission is somewhat simpler also: the Egyptian collection began in Coptic and after the decline of Coptic in Upper Egypt, the texts were translated into Arabic, then Ethiopic. Syriac apocrypha follows a simpler path, with Syriac remaining the liturgical language (and for a small group, the spoken language) of the East and West Syriac churches, and some translation occurring into Arabic, Armenian, Georgian, and Tamil. Apocryphal texts have been transmitted in Syriac throughout the history of Syriac Christianity and appear in manuscripts created as recently as the twentieth century.

But the apocryphal acts appear with less frequency than some other apocrypha, such as texts about the Virgin Mary. Of the Five Great Apocryphal Acts, only the Acts of Thomas is represented in full, and even then, the number of copies (12 at present count) is not as great as one would expect for a text that is so important for Syriac Christianity—indeed the text may be a Syriac composition. The Acts of Peter appears in two forms: as part of the History of Simon Cephas, the Chief of the Apostles (five MSS, 1 lost; translated for MNTA 1 by F. Stanley Jones) and in an excerpt of the martyrdom (in 2 MSS, one fragmentary). Hist. Sim. Ceph. is a combination of canonical tales from Acts Pet., portions of the Pseudo-Clementine Recognition, and the Preaching of Simon Cephas in the City of Rome (in 10 MSS, three from the 5th/6th cent.; appearing in a new translation for MNTA 3 by J. Edward Walters). Since the original Acts of Peter is no longer extant, Hist. Sim. Ceph. is important for reconstructing its original contents, though previous work in this regard has relied on the Latin Actus Vercellenses. A few other Syriac texts document the exploits of Peter: the Exhortation of Peter (2 MSS) and the Travels of Peter (2 MSS; both texts translated by J. Edward Walters for MNTA 2). These texts appear in no other language and may be Syriac compositions. Finally, a Syriac manuscript of the Pseudo-Clementine Romance, which depicts Peter’s conflicts with Simon Magus, has the honor of being the earliest dated manuscript in any language (London, British Library, Add. 12150; created in Edessa in 411 CE); portions of the text are found also in four other Syriac manuscripts.

The Acts of Paul is represented by a number of manuscripts of the Acts of Paul and Thecla (12 at present count, 2 lost) and two manuscripts of Paul’s martyrdom (one fragmentary). Paul’s career is also the focus of the History of Paul (appearing in a new translation from 4 MSS by Jacob Lollar for MNTA 3). Like Hist. Sim. Ceph., this text combines stories from the canonical Acts with portions of Paul’s apocryphal acts, chiefly the martyrdom. The two texts (Simon Cephas and Paul) appear together in the manuscripts and form one large work, culminating in a short conclusion where the blood of the two apostles mix together in their common place of execution. The only other known portion of the Acts of Paul is 3 Corinthians, which was valued in the Syriac church, but the evidence for the text is indirect—from citations in Aphrahat and Ephrem. The Acts of Andrew is not preserved in Syriac but there are a large number of manuscripts of the Acts of Andrew and Matthias (21 MSS, 3 lost). Some have argued that Acts Andr. Mth. was part of the early Acts of Andrew but it circulates alone in the manuscripts. Finally, of the Acts of John, only the Metastasis/Dormition is found (in 1 MS). However, John’s career in Ephesus is recounted in the History of John (9 MSS, 2 lost), which appears to be a Syriac composition. Hist. John has no overlap of material with the early Johannine acts but does contain some stories from the Acts of John by Prochorus.

As for other apostles, there is a History of Philip (10 MSS, 2 lost; translated by Robert Kitchen for MNTA 2) which appears to be a translation from Greek, but not from the Greek Acts of Philip. The Martyrdom of Luke, found also in the Egyptian corpus, appears in two manuscripts, alongside the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul mentioned above. Mention should be made also of the Doctrine of Addai, who is identified as one of the 72 disciples in the Syriac text (8 MSS) and by Eusebius in his excerpt of the Abgar Correspondence (Hist. Eccl. 1.13; though here Addai appears under the name Thaddaeus) but Mark and Matthew and the Acts of Thaddaeus identify him as one of the twelve apostles. The story of Addai continues into the Acts of Mar Mari (18 MSS, 2 lost), who is described as both a disciple of Addai and one of the 72. Entirely missing in Syriac are any tales of Bartholomew, James (son of Zebedee), James (brother of Jesus), Judas Thaddaeus, Matthew, and Simon the Canaanean; Matthias (in solo adventures) and Mark the evangelist are also absent.

The Egyptian corpus is more abundant in the manuscript tradition because of its role in liturgy; each of the texts notes the date of its protagonist’s martyrdom, indicating when the text should be read in the liturgical calendar. Something similar occurs in the Doctrine of Addai, where mention is made of the date of the apostle’s death and the command from Addai to perform a festival in his honour (Doctr. Addai 94 and 96), the Acts of Mari seems to have been read liturgically also, and Hist. Sim. Ceph. indicates in its introduction that its stories of Peter were compiled for reading on the anniversary of the apostle’s martyrdom. Otherwise, there is little evidence in the Syriac manuscripts for liturgical use of the apocryphal acts. The only other exception is the two manuscripts that combine the Martyrdoms of Peter, Paul, and Luke. These appear to be translations from their counterparts in the Egyptian corpus (from Coptic or Arabic): the manuscripts were copied at the Deir al-Sury?n in Egypt, and all three texts include dates for their subjects’ martyrdoms from both Egyptian and Syrian calendars, thereby expressing the multicultural character of a Syrian monastery in Egypt. A similar translation process seems to have occurred, but in reverse, for Hist. John and Hist. Phil., which appear a few times in Arabic manuscripts, translated directly, it seems, from Syriac.

Also in contrast to the Egyptian corpus, the Syriac apocryphal acts are rarely bundled together. Small clusters appear, but in miscellaneous codices alongside other texts; there are no manuscripts dedicated only to apocryphal acts. The known codices containing two or more apocryphal acts are as follows:

Baghdad, Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon, 199 (olim Mosul, Chaldean Patriarchate, 86) (1711/1712): Acts of Thomas and Acts of Mar Mari (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Baghdad, Library of the Chaldean Monastery, 628 (olim Alqoš, Notre-Dame des Semences, Vosté 214, Scher 112) (1885): Acts of Thomas, Acts of Mar Mari, and Acts of Paul and Thecla (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Baghdad, Library of the Chaldean Monastery, 630 (olim Alqoš, Notre-Dame des Semences, Vosté 217) (1891): Acts of Mar Mari, and Acts of Andrew and Matthias (also includes History of Matthew and the Virgin) (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Baghdad, Library of the Chaldean Monastery, shelf number not provided (olim Alqoš, Notre-Dame des Semences, Vosté 215, Scher 96) (1891): Acts of Mar Mari, and Acts of Andrew and Matthias (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Syr. 74 (17th cent.): History of Philip and Acts of Andrew and Matthias (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Syr. 75 (1881): Acts of Andrew and Matthias, Acts of Thomas, Acts of Mar Mari, and Acts of Paul and Thecla (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Karkuk, Chaldean Archdiocese of Karkuk, 213 (1723): History of Simon Cephas, History of Paul, History of John, History of Philip, Acts of Andrew and Matthias, Acts of Thomas, and Acts of Mar Mari (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

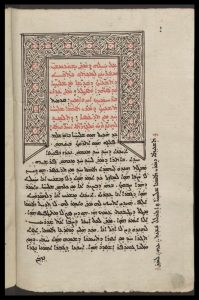

London, British Library, Add. 12174 (1197): Dormition of John, Acts of Paul and Thecla, and a portion of the Pseudo-Clementines

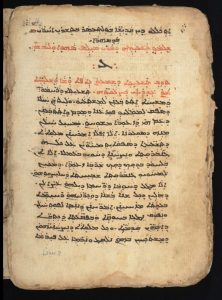

London, British Library, Add. 14645 (936): Acts of Andrew and Matthias and Acts of Thomas

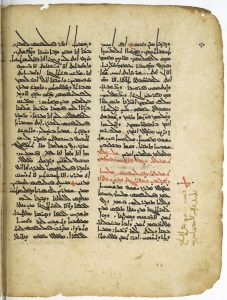

London, British Library, Or. 9391 (1890): History of Simon Cephas and History of Paul

Paris Bibliothèque nationale de France, syr. 235 (13th cent.): History of John and History of Philip (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

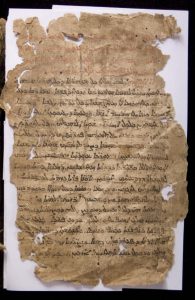

St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, Syr. New Series 4 (5th/6th cent.): History of Paul, Preaching of Peter, History of John, and Doctrine of Addai (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Tehran, Chaldean Church of St. Joseph, 8 (18th cent.): History of Philip and Acts of Andrew and Matthias (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Trichur, Chaldean Syrian Church, Syr. 9 (17th cent.): History of Simon Cephas, History of Paul, History of John, History of Philip, Acts of Andrew and Matthias, and Acts of Thomas (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Urmia, Oroomia Mission Library, 103 (1885; now lost): History of Simon Cephas, History of Paul, History of John, History of Philip, Acts of Andrew and Matthias, and Acts of Mar Mari (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. sir. 597 (17th cent.): History of Simon Cephas, History of Paul, History of John, Acts of Thomas, Acts of Paul and Thecla, and Acts of Mar Mari (MANUSCRIPTA APOCYPHORUM)

Several things are noteworthy about this list. For one, almost all of them are written in East Syriac script and originate in the region of Alqoš and nearby Urmia. Second, these manuscripts also share several other texts in varying combinations, including stories of the Finding of the True Cross, the Image of Christ, the Dialogue between God and Moses, and various lives of saints and martyrdoms. And third, likely the manuscripts with the larger clusters of apocryphal acts are directly (or near directly) related to each other (Trichur 9 and Vat. sir. 597 are particularly similar).

Given that apocrypha proliferate in Syriac manuscripts, it is a surprise to see so few copies of apocryphal acts. While it is no wonder that the Five Great Apocryphal Acts are poorly represented, given that few portions of these texts exist in any language, the numerous second-tier texts—featuring the other seven apostles and several disciples of apostles—are notably absent. In some cases, local versions of the apostles’ exploits may have been barriers to the translation of other texts—for example, Hist. John and Hist. Phil. may have made the popular Acts of John by Prochorus and the Acts of Philip superfluous. But you would expect the interest in the apostles’ lives and martyrdoms that is reflected in the Egyptian corpus, as well as the Latin Apostolic Histories, would also have taken root in the Syriac churches. Of course, Arabic was used as a spoken and written language in some Syriac dioceses—consider, for example, the Arabic manuscript of the Egyptian apocryphal acts from Dayr al-Suryan used by Agnes Smith Lewis (14th cent.) and collections of apocryphal acts in Arabic Garšuni, such as Edgbaston, University of Birmingham, Mingana Syr. 40—so we cannot rule out the circulation of additional apocryphal acts in Syriac Christianity through translation into other languages.

For those interested in working on apocryphal acts in Syriac, there are certainly some gaps in scholarship that need to be filled. The availability of Syriac manuscripts made possible through the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library has expanded our sources for almost all of the texts, making new editions a desideratum. For example, the only edition of the Syriac Acts of Andrew and Matthias appeared back in 1871 and was based on a single manuscript. Note too that only one of the published Syriac manuscripts of the Acts of Thomas contains the Hymn of the Pearl (Berlin Syr. 75)—maybe the newly available manuscripts will provide us with more witnesses. And for those who can read Arabic in Syriac letters, there are numerous Garšuni manuscripts of apocryphal acts that have yet to be explored. More texts and more versions of texts await.