“Lost Gospels” and Other Christian Apocrypha: New Discoveries and New Perspectives

On Wednesday, October 7 I delivered a virtual lecture for BASONOVA (Biblical Archaeology Society of Northern Virginia). They have granted me permission to share the text of that lecture (with some minor changes) on Apocryphicity.

Discussions of the origin and transmission of apocryphal literature in popular media, and some scholarship, typically look something like this:

Christian apocrypha are texts about Jesus and his family, followers and friends that are not found in the New Testament. They were written in the first three centuries, some perhaps as early as the late first century. They contain heretical ideas and were systematically destroyed once the church of Rome solidified its power over other forms of Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries; these repressive efforts culminated in the formation of the canon of the New Testament, established at the latest by the time of Athanasius of Alexandria. The scriptures were clearly established as the 27 books of the New Testament; nothing more should be written, copied, or read thereafter. Some apocryphal traditions survived, however, but heavily sanitized of heretical ideas and collected as writings of the saints—so-called hagiographical literature. Otherwise, Christian apocrypha were lost to history until scholars of the Renaissance found copies in Eastern monasteries and brought them home to the West to be published, and more recently from archaeologists and Bedouins who found texts in caves and ancient garbage dumps. Despite all of the efforts of the church to censure these texts, many of them are now available for everyone to read.

This description, while succinct, is problematic; virtually every sentence is wrong, or at least reflects outdated scholarship. Over the last few decades, specialists of Christian apocrypha have rewritten the history of the church’s interaction with noncanonical literature. Their results are somewhat less sensational than what I described above but, at least in my view, far more interesting.

- Christian apocrypha are texts about Jesus and his family, followers and friends that are not found in the New Testament.

The problems begin with the first two words of this sentence. The term apocrypha (singular: apocryphos/apocryphon) means secret, hidden, or mysterious. In antiquity, the use of the term was somewhat fluid. It could be used positively by some, including practitioners of magic but also Christians and Jews, for their own ‘secret books’; two Christian texts apply the term explicitly: the Apocryphon (or Secret Book) of John and the Apocryphon of James. But by the end of the second century some writers, like the bishop Irenaeus of Lyons, are using it pejoratively for texts that they considered forged or false; this meaning continues today for stories that we think may not be true. Apocrypha scholars today prefer to use the term noncanonical for these texts (as opposed to canonical), but even this convention comes with certain caveats. The New Testament canon did not arrive fully-formed from the heavens when Jesus rose from the grave. It took several centuries to formulate, so over that time period a text cannot be called noncanonical because there was no canon.

And those first three centuries or so were a productive time for the writing of texts about the early decades of Christianity. Some of these (eventually noncanonical) texts were particularly popular. The Shepherd of Hermas, for example, is mentioned favorably by several early writers, it appears on early canon lists, and is plentiful in the manuscript record (it is the most common noncanonical text in papyri); the Gospel of Peter was valued in the church of Rhossus (near Antioch) in the second century; and writers like Clement of Alexandria and Jerome appeal to the authority of the Gospel of the Hebrews and the Gospel of the Egyptians. Certainly many other texts were disparaged by writers of this period but we have to be careful to not assign too much weight to the opinions of critics, because we no longer have the testimony of the leaders of congregations who did value these texts. History, they say, is written by the victors, so it must be kept in mind that what we now call apocrypha was once someone’s scripture.

- They were written in the first three centuries, some perhaps as early as the late first century.

Most apocrypha collections on shelves of bookstore or libraries contain a fairly common assortment of texts—a canon of noncanonical texts, if you will. Typically they feature some infancy gospels, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Nicodemus, and a few other texts about Jesus’ earthly years, maybe some acts of the apostles, one or two letters, and a handful of apocalypses. The usual criterion for inclusion is composition within the first three centuries—before the establishment of the canon. This interest is due to the (largely Protestant) goal of finding in this material some traditions that go back to the first century, something that can be used to recover the life and teachings of Jesus as well as other first-century figures like Paul or James. It’s not such a farfetched idea. A few early Christian writings, such as 2 Clement, include sayings of Jesus that are not found in the New Testament Gospels, and it’s widely believed that sayings of Jesus continued to be passed down orally well into the second century. It’s important too that scholars don’t feel restricted by the canon for examining the life of Jesus; apocryphal texts may not contain much that goes back to Jesus, but they shouldn’t be ruled out for consideration simply because they are not canonical.

Nor should theories of first-century composition be summarily dismissed. I think a strong case can be made for the Gospel of Thomas and perhaps the Gospel of the Hebrews, but most importantly, the traditional view that apocryphal texts were composed after those that became canonical should not interfere with fair evaluation of the evidence for early composition. So, some apocryphal texts may have been composed as early as the first century, but I find the statement above problematic more for its upper limit: the end of the third century. Many of us who study Christian apocrypha are not particularly interested in the historical Jesus; we look at these texts more for what they say about the beliefs and practices of those who wrote and valued them, no matter when or where they were composed. And that interest doesn’t stop when we get to the fourth century; apocrypha continued to be composed after the establishment of the canon, even up to today, and each of them is worthy of close study.

- They contain heretical ideas and were systematically destroyed once the church of Rome solidified its power in the fourth and fifth centuries.

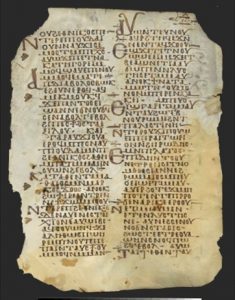

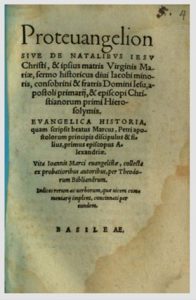

Heretical ideas, of course, are any ideas that are contrary to what is considered orthodox (correct teaching), but what is heretical can vary considerably over time and space. Take the Christology of Arianism as an example: in 325 it was declared a heresy, but ten years later it was orthodoxy, and then heresy again in 381. But note also that the texts outside the canon were not considered equally objectionable. The chief offenders were gnostic texts, which promote the view that the god of the Christian Old Testament is an evil pretender trying to trap humans in the material world; Jesus was sent from the true Father to rescue us and enable us to ascend into the heavenly realm. These are the texts that were the target of the heresy hunters who wanted to eradicate Gnosticism. Much of gnostic literature survives today due to one dramatic discovery: the Nag Hammadi Library. But gnostic texts are a relatively small sub-category of apocryphal literature. Otherwise, most apocryphal texts are orthodox in their theology and Christology and essentially expand upon rather than challenge the texts that became canonical. And these texts were very popular and widely copied. We have somewhere around 200 copies of the Protevangelium of James; similarly plentiful are the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, the Gospel of Nicodemus, and the Acts of John written by his disciple Prochorus. These texts and others are available in a range of languages—Greek, Latin, Syriac, Slavonic, Georgian, Armenian, Irish—a testimony to how far and wide this material traveled over the centuries.

It’s surprising that so many copies of apocrypha exist given that we have plenty of testimony from church writers instructing their audience not to read them. But maybe we need to adjust our thinking: rather than ask why are these being copied if the church forbids it, we should ask why are these writers forbidding texts that are clearly very popular. So, if destruction of apocrypha was the church’s intent, they were not very successful at achieving their goal. Yes, some texts we now know only from lists of banned books, and some exist only in fragments, but it seems to me that, for the most part, such texts do not survive simply because they were not particularly well-liked, or because the groups who did value them faded away.

- These repressive efforts culminated in the formation of the canon of the New Testament, established at the latest by the time of Athanasius of Alexandria. The scriptures were clearly established as the 27 books of the New Testament; nothing more should be written, copied, or read thereafter.

In 367 Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, issued his annual letter for Easter. In it he describes the New Testament as the 27-book collection that has since become standard. He does mention a few others as useful for the instruction of catechumens: the Didache and the Shepherd of Hermas. But as for other texts, he says, “there should be no mention at all of apocryphal books created by heretics, who write them whenever they want but try to bestow favor on them by assigning them dates, that by setting them forth as ancient, they can be, on false grounds, used to deceive the simple minded” (trans. Bart Ehrman, Lost Scriptures, p. 340). Typically, Athanasius’s letter is presented as evidence for the closing of the canon and the end of the production of apocryphal literature; people imagine bands of church officials traveling throughout the empire, pillaging monastic libraries and burning banned books. But the evidence tells us a different story.

First, just because Athanasius says it’s so, doesn’t make it so. From Egypt alone we have two biblical codices—the Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus—that likely post-date Athanasius and include texts that Athanasius considers noncanonical: Siniaiticus contains Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas and Alexandrinus contains 1 and 2 Clement. Also, scribes in Western Europe added Paul’s Epistle to the Laodiceans to a number of Vulgate Bibles (such as the Codex Fuldensis, from 546). Then there are Christian communities in the East who had other views on the canon; Syrian and Armenian Bibles, for example, used to include a third epistle to the Corinthians, the Coptic church also had 1 and 2 Clement, and even today the Ethiopian canon features a few additional texts, including the Book of the Covenant and the Book of the Rolls. So, a 27-book canon is not certain for everyone, everywhere.

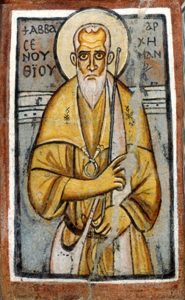

It’s also not clear how readers would understand Athanasius’s ruling. Let me give you an example. Shenoute of Atripe was archimandrite of the White Monastery in Upper Egypt for about 80 years starting in 385. He was a supporter of Athanasius and apparently set up the Easter letter as law in his monastery. Shenoute even wrote against apocrypha in one of his writings, I Am Amazed:

“those who write apocrypha are blind, and blind are those who receive them and who put their faith in them.” (I Am Amazed, par. 101; trans. Hugo Lundhaug and Lance Jenott, The Monastic Origins of the Nag Hammadi Codices [STAC 97; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015], 170–75).

“Even if they proclaim the name of God (in them) or speak correct words, all the evil things that are written in them destroy the other that is good.” (par. 384)

“He who says ‘I know,’ because he reads apocrypha, he is a most unlearned one, and he who thinks that he is a teacher when he memorizes apocrypha, he is even more unlearned.” (par. 317–18)

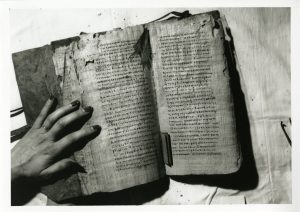

Despite what appears to be an explicit condemnation of apocrypha, the remains of Shenoute’s library contain a number of apocryphal texts—including several homilies that incorporate apocryphal traditions, and an assortment of apocryphal acts. How do we account for this? It’s possible that Shenoute considered certain theologically-dubious texts “apocrypha” but more-palatable texts perfectly acceptable. So, what is “apocryphal” for Shenoute depends more on a text’s contents than whether or not it is included in the canon.

Some of the texts found in the White Monastery’s library belong to a sub-genre of apocrypha called apostolic memoirs. Each of these texts begins as a homily delivered on a particular day by a famous church leader—such as Basil of Caesarea (though these leaders did not actually write the homilies)—but quickly become something else. The writer tells the reader that he found an ancient text in, usually, a house or church in Jerusalem, and then presents the contents of that text, which, of course, is a complete invention. These embedded apocryphal texts include tales of John told by his apostle Prochorus, accounts of the Dormition of Mary by the apostles, and a letter by Luke about the building of the first church dedicated to the Virgin. We have lots of these memoirs—it was a very common form of literature in fifth-century Egypt. Their goal was to provide scriptural authorization for the consecration of sacred sites and the establishment of festivals in a newly-Christianized Egypt; they were used to build a religion. We have a similar phenomenon in the West, with homilies incorporating traditions from the Gospel of Nicodemus about Jesus descending to hell and liberating the patriarchs. So, even after the apparent closing of the canon we have orthodox Christians creating fake first-century texts to be read on certain days in the liturgical calendar; these texts are not canonical but they are not really apocryphal either, and their writers certainly had no qualms about writing such material even at the same time as they condemned other writings as “apocryphal.”

- Some apocryphal traditions survived, however, but heavily sanitized of heretical ideas and collected as writings of the saints—so-called hagiographical literature.

This statement is not far off from the truth. There is a category of apocrypha known as apocryphal acts of the apostles, which feature tales of the exploits of individual apostles—so, the Acts of Thomas, the Acts of Peter, the Acts of Paul, etc. It is believed that the earliest of these texts were composed in the late second and early third centuries. Some of the theology of the apocryphal acts was objectionable to the orthodox Christians who determined the shape of the canon, but they really liked the martyrdom portions of the texts and continued to circulate those, sometimes with one or two additional miracles. These abbreviated acts became part of the liturgy in Eastern and African churches, to be read on the anniversaries of the saints’ martyrdoms. In the West, portions of the apocryphal acts were collected in compendia such as the widely popular Golden Legend composed by Jacob of Voragine.

Typically though, this material is classified not as apocrypha but as hagiographa—writings on the saints. But this is a really broad category because it includes not only accounts of early Christian, biblical characters but also writings on other figures from over the centuries, such as St. George or St. Perpetua. To me, if a story features a biblical saint, then the text fits the definition of apocrypha. Perpetuating such a division between apocrypha and hagiographa feeds an artificial distinction of apocrypha as early, rejected, and heretical, and hagiographa as continually created, valued alongside the Bible, and orthodox. Some apocryphal acts were newly composed after the fourth century—why edit apocryphal acts when you can just create new ones? And we have numerous manuscripts of these “later acts,” written in a variety of languages, and clearly intended for liturgical use. This evidence testifies to the importance of tales of the apostles in the lives of Christians and challenges the distinction between apocrypha and scripture.

- Otherwise, Christian apocrypha were lost to history until the explorers of the Renaissance found copies in eastern monastery libraries and brought them home to the West to be published, and more recently from archaeologists and Bedouins who found texts in caves and ancient garbage dumps.

As we have seen, Christian apocrypha were not really “lost”; well, okay, some texts we only know now by their name, and some were unknown to us before they were found by archaeologists or Bedouins. But for the most part these texts were lost because they fell out of use (they simply were not popular) and because of the destruction of ancient libraries by invaders, not because of a coordinated effort to destroy anything noncanonical. The majority of apocryphal texts were copied and transmitted continually over the centuries by scribes of monasteries in both the East and the West. Certainly the texts that were popular only in the East were not known to the West until the Renaissance but considering them “discovered” is a colonialist view that our field needs to leave behind. The Renaissance, then, marks the beginning of the transition of apocrypha from manuscript to print, not the rediscovery of apocryphal texts lost for centuries.

- Despite all of the efforts of the church to censure these texts, many of them are now available for everyone to read.

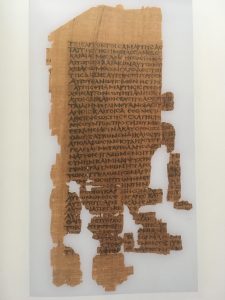

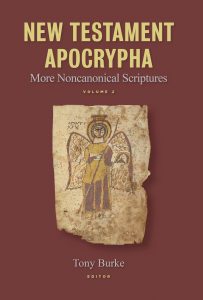

This last sentence is actually true. Apocrypha scholars have worked diligently to publish these texts by gathering manuscripts, carefully working to determine their original readings, and creating critical editions and translations. My own doctoral work involved creating an edition of all the known Greek manuscripts of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and I recently published an edition of the Syriac manuscripts. I have also worked on creating editions of several other texts: the Acts of Cornelius the Centurion, a Homily on the Funeral of Jesus, the Legend of the Thirty Pieces of Silver, 3 Apocryphal Apocalypse of John, and the Questions of James to John. This is the aspect of work on apocryphal texts that I find most exciting, particularly when I find a new copy of a text that has not been mentioned in previous scholarship, or better yet, something entirely new. And publishing new texts is the goal of another one of my projects: the More New Testament Apocrypha series. This is a multi-author work featuring translations of texts that have not previously appeared in English translation or sometimes in any form at all; two volumes have appeared so far and a third is on its way. Anyone who wants to learn more about Christian apocrypha can also consult the e-Clavis, an online, open-access resource created by the North American Society for the Study of Christian Apocryphal Literature (NASSCAL). The web site (available at www.nasscal.com) features over 150 entries with summaries of the texts and links to translations and editions, manuscripts, and other sources. Though sometimes denounced, apocrypha have endured over time, and today, thanks to the work of organizations like NASSCAL, they can be read by anyone, virtually anywhere.

This last sentence is actually true. Apocrypha scholars have worked diligently to publish these texts by gathering manuscripts, carefully working to determine their original readings, and creating critical editions and translations. My own doctoral work involved creating an edition of all the known Greek manuscripts of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and I recently published an edition of the Syriac manuscripts. I have also worked on creating editions of several other texts: the Acts of Cornelius the Centurion, a Homily on the Funeral of Jesus, the Legend of the Thirty Pieces of Silver, 3 Apocryphal Apocalypse of John, and the Questions of James to John. This is the aspect of work on apocryphal texts that I find most exciting, particularly when I find a new copy of a text that has not been mentioned in previous scholarship, or better yet, something entirely new. And publishing new texts is the goal of another one of my projects: the More New Testament Apocrypha series. This is a multi-author work featuring translations of texts that have not previously appeared in English translation or sometimes in any form at all; two volumes have appeared so far and a third is on its way. Anyone who wants to learn more about Christian apocrypha can also consult the e-Clavis, an online, open-access resource created by the North American Society for the Study of Christian Apocryphal Literature (NASSCAL). The web site (available at www.nasscal.com) features over 150 entries with summaries of the texts and links to translations and editions, manuscripts, and other sources. Though sometimes denounced, apocrypha have endured over time, and today, thanks to the work of organizations like NASSCAL, they can be read by anyone, virtually anywhere.

Gospel from Longinus ( fragment) God so hated the world full of evil, that he gave his one and only Son for judgement and plague for seekers and them that mourn that whoever believes in him should have still small voice and love and that his chosen people should judge and put to death this world and return him his Son by that.