Some Reflections on Ariel Sabar’s Veritas

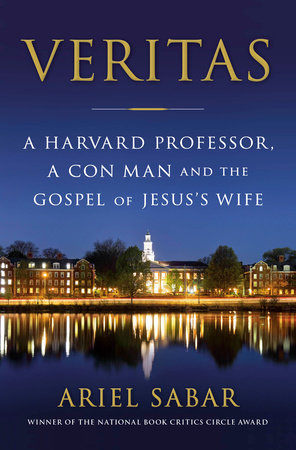

Scholars, or at least those scholars in my small corner of academia, have been gleefully reading (some hate-reading) and reviewing Ariel Sabar’s new book Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. I’m a bit late to the party, but I seem to be among the few who did not get sent an advance copy (sheesh!) and was further delayed because there were no stores within 50 km of me that bothered to stock the book on the day of its release. To me (and my colleagues) this book is important—why isn’t it important to everyone? Sigh. Truth be told, academics seem to both delight in and dread when outsiders (Sabar is a journalist) look into our world; it’s very much how Canadians feel living in the shadow of the US: they noticed us! (But did they have to be so mean?).

Scholars, or at least those scholars in my small corner of academia, have been gleefully reading (some hate-reading) and reviewing Ariel Sabar’s new book Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. I’m a bit late to the party, but I seem to be among the few who did not get sent an advance copy (sheesh!) and was further delayed because there were no stores within 50 km of me that bothered to stock the book on the day of its release. To me (and my colleagues) this book is important—why isn’t it important to everyone? Sigh. Truth be told, academics seem to both delight in and dread when outsiders (Sabar is a journalist) look into our world; it’s very much how Canadians feel living in the shadow of the US: they noticed us! (But did they have to be so mean?).

As other reviewers have said, Veritas is an excellent book. If you read Sabar’s piece on GJW for The Atlantic, you know that Sabar is a gifted investigator and writer, though here Sabar has adjusted his style so that readers are treated to a page-turning thriller. But he is no less strong an investigator. At several points in the book I felt like he had followed the evidence as far as he could, but then he went deeper, and found more. Who would have thought the trail would lead him to wandering around Bad Wurzach looking for men who were altar boys in the seventies? He is also extremely good at communicating the intricacies of the forgery hypothesis to people outside of academe who would have no clue about such things as interlinear translations and the lifespan of Lycopolitan Coptic. And who could expect that a play-by-play account of a conference presentation (with exchanges between King and Alin Suciu, Madeleine Scopello, and others) could be so exciting?

All of that said, I’m a scholar—in particular, one who works with literary criticism and textual criticism—so I am compelled to pore over Sabar’s book and find problems, inconsistencies, and errors of fact. Maybe this is just my defensive reaction to his attack on “elite” scholarship, or more specifically, his unfavorable depiction of one of our own (Karen King, well-regarded for her work on the Gospel of Mary and her book What is Gnosticism?); maybe I just need a break from trying to figure out how to teach my courses over Zoom. Regardless, for anyone interested, here are some of my thoughts on Veritas.

1. Among the journalistic techniques used by Sabar is the description of physical qualities of the people he encounters. These descriptions vary in detail depending on the subject’s importance to the story; so we learn a lot about King and Fritz, but less about people like Hannah Veale, who is described only as “a television producer with long blond hair” (65). While such attention to physical attributes is helpful for readers to visualize the characters, it is perhaps striking to scholars who are encouraged to focus on their colleagues’ bodies of work not their . . . well, bodies. Some of the discomfort is due also to the currency of the events—I would have less of a problem with this level of detail in describing, say, nineteenth-century scholars, but for people I know, it seems . . . invasive, particularly when discussing King’s illness (p. 20), which does not seem germane to the story. At one point, the level of detail is so deep that it becomes comic. In describing Christian Askeland’s reaction to his discovery of the problems with the manuscript of Lycopolitan John, Sabar writes: “His head throbbed on the train home. He had been working late that week, and he’d looked forward to a relaxing dinner with his wife, Stephanie, their three children, and Stephanie’s mother, who was visiting from Florida. Warm plates of lasagna and calzone were waiting on the dinner table when he walked in” (136). I’m not sure what is more ridiculous: that Askeland would volunteer this information or that Sabar would press him for it (Whoa, slow down a second, Christian. First tell me, what was your wife serving for dinner that night?). We expect and want journalists to document what they see, but the description of the Askelands’ meal is not based on Sabar’s own observations, leaving the reader wondering if he is embroidering the story, and if so, does he do this elsewhere in the book? Can we trust what we are reading?

2. Sabar can be a little imprecise at times. He mentions that “no fewer than three Gnostic texts depicted conflicts over [a Mary], and in each case that woman was Mary Magdalene” (16), but you will learn from his notes that only one of these texts actually call her Magdalene (Pistis Sophia should also be included in this list, and this text does identify Mary as the Magdalene). Later Sabar criticizes King for the same imprecision: “King, who titled her book The Gospel of Mary of Magdala, even though the gospel nowhere identifies its ‘Mary’ as Magdalene” (279). In an exchange on Twitter, Janet Spittler took issue with Sabar’s offhanded statements about the authorship of Paul’s letters: “the apostle Paul writes in his First Epistle to Timothy” and “If women have questions, he writes in his First Epistle to the Corinthians” (11; see also p. 18 where Paul’s views on women in the church in 1 Timothy are contrasted with the asceticism of Marcion). Spittler remarked that a book about a modern forgery should be more precise in its discussion of ancient texts (or portions of texts) forged in Paul’s name. Sabar countered that he did mention scholars’ views on Pauline authorship in the notes and he needed to keep the discussion simple for lay readers, but he had no problem with nuance when mentioning the “anonymous second-century author who wrote 3 Corinthians in the name of the apostle Paul” (17). Statements about Pauline authorship and early dating of the canonical Gospels are typical “virtue signals” to readers; these comfort conservative readers that the author is “on their side.” Sabar’s decision to bury consensus scholarship on Paul in the notes is an indication of who Sabar sees as his audience. In another section of the book, Sabar discusses Mark 16:9, an addition to the text made by a later copyist who added the detail that Jesus “appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons.” On this addition, Sabar writes: “In a single opening volley, this scribe, whom some scholars prefer to call a forger, had telegraphed the vicious cycle of promotion and demotion that would become Mary’s lot” (60). This gives too much power to the copyist, because the details he adds to Mark are drawn from John and Luke, so if anyone deserves credit or condemnation, it is the authors of the Third and Fourth Gospels. And no one would call them forgers, nor do I think anyone really uses that term for the creator of Mark 16:9.

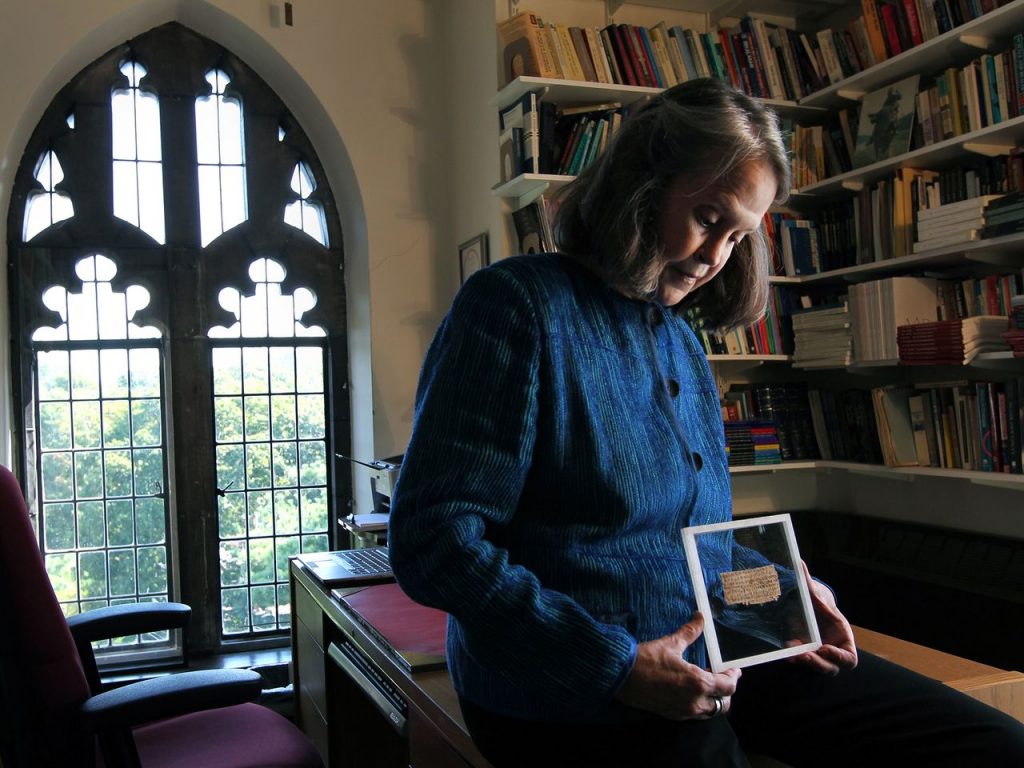

3. Throughout the book, Sabar highlights the divide between elites and non-elites. He (quite rightly) applauds the contributions made to proving GJW a forgery by bloggers and independent scholars Andrew Bernhard and Michael Grondin, as well as Askeland, who is a trained scholar but is presented as operating outside mainstream scholarship (and his contributions did appear also on a blog). Against these outsiders, Sabar plays ivy-school scholars like King and Roger Bagnall. And much of his book is a take-down of the elitism of Harvard and the relationship between the Divinity School’s scholars and Harvard Theological Review, the journal that published King’s initial work on the text. Sabar also highlights the David and Goliath nature of the two camps by including photographs of Bernhard and Grondin in their home offices (and Askeland in a humble cubical), juxtaposed with finely composed shots of King and Bagnall in their university offices. Fritz too is wrapped up in the politics of elites vs. non-elites; though apparently intent on embarrassing ivory-tower scholarship he calls critics of GJW “country-level manuscript experts” from the “University of Pee-Pee Land” (202). Other comments in the book disparage academia, such as Sabar’s description of the Coptic Studies conference in Rome as “an obscure academic conference” of “elite scholars” (xi)—obscure to whom? Aren’t all academic conferences “obscure” to outsiders? And why are the participants considered “elite”? A later description is more irenic—he says the conference “brought together the world’s foremost specialists in Coptic language and culture” (87)—but here it seems he aims to highlight the criticism elicited by King’s presentation (so King is presented as chastised by her betters). Similarly, Evangelical Textual Criticism is called a “little-known blog” (139) though it is actually well-known to both evangelical and non-evangelical scholars; Sabar’s comment seems designed to emphasize Askeland’s outsider status. I won’t argue that blogs quickly advanced discussion on this text, but the dichotomy between established scholars and bloggers is artificial: several bloggers instrumental in the discussion are also scholars (Mark Goodacre, Francis Watson, Alin Suciu) and a range of scholars contribute to ETC. Sabar concludes that “Truths honed in basements might take a bit longer to find their way into the ivory tower, but they got there eventually” (144), but the larger lesson from the GJW story is the value and necessity of a properly functioning referee process, which can be agonizingly slow, but blogging also has its problems precisely because it is largely unchecked, leading to the publication of wild speculation, unfortunate faux pas (Askeland’s poorly chosen “ugly step-sister” and “pimping” analogies), and ugly ad hominem attacks (Leo Depuydt’s bizarre response to King’s work published on Goodacre’s blog) that would not be acceptable in refereed journals.

4. Given that Sabar’s focus is on a noncanonical gospel forgery, he naturally brought into the discussion Morton Smith and his controversial Secret Gospel of Mark, a longer version of the canonical Gospel excerpted in a letter from Clement of Alexandria to a certain Theodore. Full disclosure: I am inclined to believe that Smith did not forge the text, leaving several other possibilities for its creation—it’s an authentic ancient letter composed by Clement or someone else from antiquity (either accidentally or intentionally attributed to Clement), or it’s a creation as recent as the eighteenth-century book in which the letter was copied and found by Smith in the Mar Saba Monastery. But Sabar is apparently unaware of the range of scholarship on this text; he sees it only as a forgery. He characterizes the text as depicting “a gay Jesus whose followers are saved by sin” (34), and says Jesus here “spiritually initiates [a young man] through what appears to be a gay encounter” (33; see also 74). Other than Smith, the only Secret Mark scholar he cites (other than a brief mention of Robert Price, who is hardly an expert) is Peter Jeffery, whose list of apparent double entendres in the text is generally dismissed even by forgery proponents. One of these is cited by Sabar: “Clement vouches for the authenticity of a different passage, in which Jesus rejects women” (33)—an interpretive stretch (Jesus refuses to see three specific women, he does not “reject women”). Why would Sabar appeal to Jeffery of all people? Perhaps because Jeffery’s eagerness to see something sexual in all of Jesus’ actions in the text (see my next point), or maybe because of Jeffery’s credentials (he is introduced as “the Princeton scholar Peter Jeffery, a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant winner,” [34]; is Sabar trying to use prestige for his own benefit here? Sabar also misrepresents some aspects of Smith’s discovery with the intent, it seems, to make Smith out to be a twentieth-century Walter Fritz. He says, “Morton Smith never produced the book he’d claimed to have found” (35), which is quite misleading, implying that the book never existed or if it did, that Smith should have removed (stolen?) the manuscript from the monastery library where it was found. To be clear, Smith’s treatment of the manuscript was above reproach and commonplace: he cataloged the library, noticed something of interest, photographed it, and left it where it was found. And other people did see the manuscript; it is not Smith’s fault that it is now lost. But these facts do not fit Sabar’s narrative. He goes on to say, “If Smith were indeed the forger, his use of copies of copies of copies took some of the bloom off his rose. A more skillful con man would have fabricated an ancient document, an original that could withstand firsthand scrutiny by both humanities scholars and laboratory scientists” (35). So Smith’s failure to act like a “skillful con man” makes him a poor con man; but maybe it just means he was not a con man at all. And what does Sabar mean by “copies of copies of copies”? It is truly rare to discover an autograph of a text, and Smith worked firsthand with the only known copy of this text and included photographs of it in his monograph—that’s pretty much as close to a text as you can get. And there was nothing stopping readers from seeing the manuscript themselves; until, of course, it went missing. On this development, Sabar suggests that Smith intentionally delayed publishing his work (a decade and a half after the text’s discovery) to allow the manuscript time to “mysteriously vanish” (125)—so, is there an agreed-upon time for such things to happen? Did Smith think, ah fifteen years, the thing must have gone missing by now? Finally, Sabar mentions an exchange of letters between Smith and Roger Bagnall in which Smith inquires about some forged ostraca. Sabar writes: “It looked very much as if Smith were fishing for insights into how to get a forgery past the likes of Roger Bagnall” (36)—well, not really, because Bagnall’s answers indicate that such forgeries cannot get past someone like Bagnall. Sabar states further that Bagnall’s publication of one ostracon later declared authentic, “makes no mention of Morton Smith’s bizarre questions about it three decades earlier” (37)—but what is so bizarre about asking your colleague who is working with possible forgeries about how to detect forgeries? And why would this warrant mention when the material is published? I would imagine a number of people had similar conversations with Bagnall (Sabar does concede in a note that “It is also possible that he had an entirely innocent interest in forgeries”; indeed, many of us do—does that make our work circumspect?). Sabar is also deficient in his presentation of scholarship on another noncanonical text: the Gospel of Judas. He mentions only the original interpretation of the text advocated by the team of scholars working under the aegis of the National Geographic Society, that “rather than being Jesus’s betrayer, the text suggested, Judas Iscariot was his close friend and favorite disciple” (83). Nothing is said about the re-evaluations of the text by April DeConick and Louis Painchaud that even the NGS scholars conceded were correct. Addendum (1 Sept. 2020): Sabar pointed out on Twitter that he does include a note stating that the NGS interpretation “was not a unanimous view.” But no details are given about contrary views.

Addendum (1 Sept. 2020): I consulted with Allan Pantuck, one of the leading scholars on Secret Mark and (full disclosure) a proponent of the theory that Smith did not forge the text, about the Smith-Bagnall correspondence. A few points are worth mentioning. The correspondence comprises a number of letters written to Bagnall from Smith; there are no letters in the Smith archive at the Jewish Theological Seminary from Smith to Bagnall, so we only have one side of their conversations. The letters, Pantuck said, deal with “mostly office politics and historical minutiae.” Only two are relevant for the discussion of forgeries. In the first, dated 17 April 1977, Smith acknowledges having obtained a copy of Bagnall’s book on ostraca, briefly mentions the one left out of the book because Bagnall thought it was fake, and suggests publishing it because it “would be both instructive and amusing.” The remainder of the eight-page letter is a detailed engagement of the materials in the book. The second letter, dated 21 May 1977, was written in response to Bagnall sending him an image of the “fake” and includes the question about what made Bagnall think it a forgery. Then almost two pages follow with Smith’s suggestions about how to decipher the writing. The two letters hardly strike me as “fishing for insights into how to get a forgery past the likes of Roger Bagnall,” as Sabar states (36). As for Smith not producing the manuscript, Pantuck remarked, “Not only did he publish a description of the find in the journal of the Patriarchate” (New Zion 52 [1960]), “but he communicated by letter with the Patriarchate to notify them of his discovery.” And did Smith deliberately delay publishing the Letter to Theodore to allow time for it to “mysteriously vanish” (125)? Pantuck said that Smith “had already submitted a completed manuscript to Oxford press by the mid 1960s, which was rejected after a big battle, and then Smith requested help from Goodenough and others to help find a publisher. When you read his letters you get his mindset that the discovery was important and he wanted to get it published as soon as possible.” My thanks to Allan for sharing the results of his research.

5. Sabar seems to take much delight in highlighting sexual aspects of his investigation. Gender politics is certainly central to the story, and the investigation does take a bizarre turn when we learn about the Fritzes’ pornography business. But do we need to know the entire contents of the bawdy scene that appears on the ostracon published by Bagnall (36-37)? Is it important that Bernhard and Grondin broke with their religious traditions over the institutions’ conservative attitudes toward sex? (112, 118; and note also Askeland’s connection to the discussion on p. 143). And I suspect that the choices Sabar made about his presentation of scholarship on Secret Mark (i.e., focusing on Jefferey’s work on double entendres and on the position that the text features a “gay Jesus”) were intended to contribute to this theme of the book.

6. So intent is Sabar on making connections between disparate information, that he ascribes to Fritz some pretty clever manoeuvres. Sabar writes, “It was perhaps nothing more than coincidence, but I noticed later that the date of Fritz’s first email to King—July 9, 2010—was 114 years, to the day, after German scholars announced their discovery of the Gospel of Mary” (252). This is the same number of sayings that make up the Gospel of Thomas and the precise number of the saying that features a conflict between Peter and Mary. “With a single number,” Sabar writes, “that must have been little more than an inside joke, he had linked his fake gospel to the authentic ones with which he’d built it (Thomas) and lured his mark (Mary)” (252). Notice that “perhaps nothing more than a coincidence” is quickly upgraded to “little more than an inside joke.” I’m surprised that Sabar does not see a similar signal in the video he describes of Fritz and his wife copulating in front of a bookcase that holds a copy of Holy Blood and Holy Grail (255). This search for numerological connections and the effort put into poring over the background of porn videos indicates that Sabar worked way too long and too hard on this story.

7. I was certainly struck by some of King’s actions in dealing with GJW and don’t want them to be casually dismissed. What made her decide to work on this text, which to her, at first seemed to be an obvious forgery? Why did she emphasize the sensationalism by calling it a part of a “gospel” (rather than a homily), then by courting journalistic interest in the text, but also declaring that “In talking to the press, a big part of my task is to throw cold water on sensationalism and let the good history have a say” (103)? If she thought the text was authentic then why was she so reluctant to provide images of the manuscript to scholars at the Coptic Studies conference? Why was she so resistant to investigate the manuscript’s provenance? Suspicious also is her use of a portion of her draft article on GJW in an article on the Gospel of Philip, written to pre-emptively establish a context for GJW as a text in conversation with other texts on Jesus’ marital status. Sabar answers these questions with a chapter on the inner workings of changes proposed to the administration of Harvard Divinity School, but I’m not satisfied that King is the Machiavellian mastermind that Sabar makes her out to be. I barely know King. I only ever had one interaction with her: we were introduced at a boozy Harvard reception during SBL a few years ago, and the conversation was awkward (as are most of my social interactions at conferences, frankly). But she does, unfairly, come off as the villain here, particularly as a result of the structure of the book: we are left at the end of Fritz’s story feeling sympathetic (due to his account of abuse by a priest) but then we turn back to King, who goes from hapless dupe to middling scholar to calculating puppet master. I also think that King’s comments at public appearances, most of which are off-the-cuff remarks, are likely not representative of her scholarly views and practices, and that her approach to categories in What is Gnosticism? is misrepresented (“she cloaked what were primarily ethical positions in the guise of empirical history” [325], Sabar writes, but King expressly states in the book that “my purpose is pre-eminently ethical” [245], that is, she is critiquing how scholars use ‘Gnosticism,’ and her admission here, in an eight-page “Note on Methodology,” is hardly “cloaked”). There are good reasons why King is respected by students and scholars, but Sabar makes her out to be a kook who wrangled her way into a job she didn’t deserve.

8. Most important in all this, of course, is my near-absence from the book. As soon as I got my hands on a copy, I flipped to the index to see if I’m mentioned. Nope. Sigh. But my name does show up a few times in the notes (as editor of the York Christian Apocrypha Symposium volume on Secret Mark, for the source of a quotation from Peter Jeffery, and the York volume entitled Fakes, Fictions, and Forgeries, for a quotation from Janet Spittler). I appear also as one of the “editors of a new book of noncanonical scriptures” approached by Andrew Bernhard in the hopes of contributing a translation of GJW (111). I’m not really so narcissistic to think I contributed enough to the GJW story to warrant more mention (but hey, he could have thrown me a bone for my article “Apocrypha and Forgeries: Lessons from the ‘Lost Gospels’ of the Nineteenth Century,” which looks at Secret Mark and GJW in the context of efforts to prove modern apocrypha are indeed forgeries), nevertheless, I do think it is unfortunate that the essays by James McGrath, Caroline Schroeder, and Janet Spittler from Fakes, Fictions, and Forgeries are not put to good use, particularly since they deal with topics central to the book (ivory tower elitism, sexism in academia, the role played by blogs, etc.). To bring these articles into the discussion on Veritas, I have made two of them available HERE.

As far as examinations of the academic world (and specifically of apocryphal texts) written by outsiders go, Veritas is about as good as it gets. It is a carefully and vividly written account by someone who was an observer of the events right from the start. But I don’t think this is the end of the story for GJW. For some of us who are interested in apocrypha in all its forms, the GJW affair is not an embarrassing episode to be dismissed and forgotten, but a lesson in how and why apocrypha are created, as well as a demonstration of the conflicts that arise from their interpretation, and the efforts by those in authority to declare them unworthy of study.

Thanks for the shout-out Tony!

The bad news is nobody cares. The good news is nobody cares. Excellent summary Tony!

Thanks for your views. I have reviewed it elsewhere (including amazon). Sure, there are passages anyone may question. For example, pages 9 and 10 twice suggest that heresy-hunter Epiphanius lived in the second century rather than considerably later. And good point about the Gospel of Judas. But Veritas, overall, imo, is well-researched and well-written.

In my reading of the book, Fritz does not come off in favorable light. But on the Sept. 1 Addendum:

My list of Smith JTS archive documents is not at hand at the moment. Did you mean to write on no Bagnall letters to Smith so that we have only one side?

It might be interesting to hear from Allan (who has indeed done considerable research) or others about the reasons OUP rejected Smith’s book “after a big battle.”

Bagnall and Smith were colleagues in the History Department at Columbia. Bagnall was one of the speakers at Smith’s memorial service, and he donated their correspondence to Columbia after Smith’s death. Smith did not retain any of Bagnall’s letters, so there is nothing equivalent at JTS.

Regarding the “big battle,” my recollection is that the unofficial word that came back was that one of the OUP reviewers objected to something in the section on the historical background, which ultimately led to the manuscript being rejected, after much discussion. I would have to go back to my notes to refresh myself on the details, which I haven’t looked at in more than 10 years. If I recall correctly, Smith then went to Erwin Goodenough for advice, Jacob Neusner suggested submitting to Brill, but finally Krister Stendahl convinced him to submit to Harvard UP, which is where it ended up being published.