The Infancy Gospel of Thomas as Pilgrimage Guidebook

Last summer I was invited to a conference at the Universität Regensburg on the topic of “Extracanonical Traditions and the Holy Land” (July 2–5, 2019); you can read a summary of the conference by Jan Bremmer HERE and the papers will be published next year. Tobias Nicklas, who convened the conference, knew of my work on the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and asked me to contribute something on the text. I have to confess, it seemed a bit of a stretch. What can Infancy Thomas possibly have to say about Palestine? As it happens, a few scholars have actually tried to make connections between the text and Jewish Christianity as well as arguing for Palestine as a place of composition. But their work, or at least these aspects of their work, has not been taken very seriously by other scholars. Still, as I revisited the paper to prepare it for publication I was struck by how the text connects to certain pilgrimage locations in late antique or Medieval Nazareth. I can see now how the text COULD have been used as a sort of pilgrimage guide to the city (though I’m not so sure it was).

There are several pilgrimage accounts that mention sites in Nazareth. The earliest of these is the anonymous pilgrim of Placentia, who traveled the Holy Land around 560–570. The pilgrim mentions three locations in Palestine that have some connection to stories in Infancy Thomas. The first portion of the account mentions a synagogue where Jesus learned letters and a house of Mary:

We traveled on to the city of Nazareth, where many miracles take place. In the synagogue there is kept the book in which the Lord wrote his ABC, and in this synagogue there is the bench on which he sat with the other children. Christians can lift the bench and move it about, but the Jews are completely unable to move it, and cannot drag it outside. The house of St. Mary is now a basilica, and her clothes are the cause of frequent miracles. (Itinerarium 5; trans. John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades [Warminster 2002], 79–80)

The synagogue connects with the three accounts of Jesus and a teacher found in Infancy Thomas (chs. 6, 14, and 15). In the first, Jesus is encouraged by a teacher to come into his schoolroom. The teacher tries to teach Jesus the alphabet but Jesus is silent. The teacher becomes frustrated and strikes Jesus on the head. Then Jesus tells him that he already knows everything there is to know and tells him arcane qualities of the letter Alpha (or Aleph in some early versions). The second story is much like the first but this time Jesus returns the teacher’s abuse with a curse, striking the teacher dead. In the third version, Jesus goes into the schoolroom, opens a book and reads from it, thus again demonstrating that he does not need to be taught. The pilgrim’s account is vague enough that it need not be dependent on direct knowledge of IGT—naturally there would be some interest in where Jesus went to school, and a synagogue would be the expected location. Some aspects of it also strain credulity: are we to believe that the Jewish community in Nazareth was inviting Christians into their synagogue to see a bench given miraculous properties by someone who they would deny HAD miraculous abilities? As for the house of Mary, there is little explicit mention of such a house in Infancy Thomas beyond a few references to Jesus returning home after his encounters with teachers (14:1; 15:1). A house of Mary (perhaps the same one seen by the pilgrim of Placentia) was visited by the monk Arculf in 670 (recorded by Adomnán of Iona, De Locus Sanctis 2.26). In Arculf’s account, a church, called the Church of the Nutrition, had been built over this house. Over time the location of the building was lost but recent excavations in the area described by Arculf may have uncovered the church and the home beneath it. You can read about these excavations in this article from Livescience.

The third location related to Infancy Thomas mentioned by the pilgrim of Placentia is not in Nazareth but in Jericho:

It is a six-mile journey from the Jordan to Jericho, and when you see Jericho it is a paradise. . . . The stones which the children of Israel brought up from the Jordan are in a basilica not far from Jericho. They have been placed behind the altar, and they are huge. In front of the basilica is a plain, the Lord’s Field, in which the Lord sowed with his own hand. Its yield is three pecks, and it is reaped twice in the year, but it grows naturally, and is never sown. They reap it in February, and then use the harvest for communion at Easter. After this harvest they plough, and the next reaping is at the time of the other harvesting, after which it is ploughed and left fallow. (Itinerarium 13; trans. Wilkinson, ibid., 82)

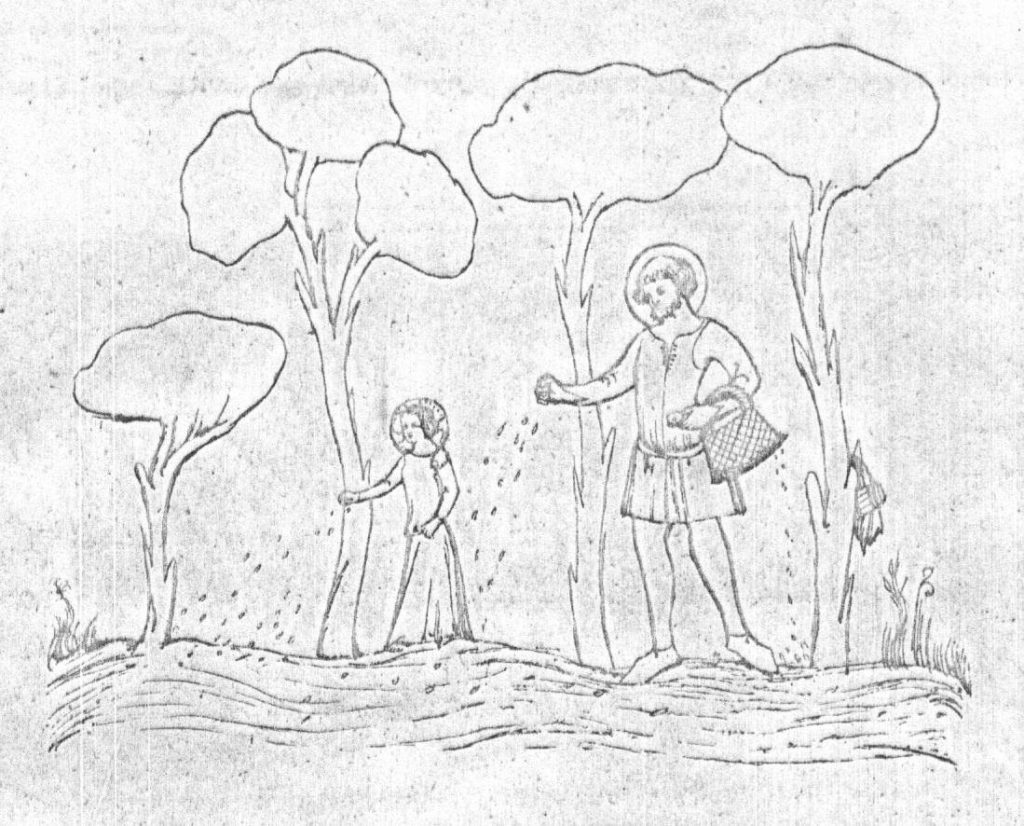

The account evokes the story of the Miraculous Harvest in Infancy Thomas 12:

And at the time when Joseph was sowing seeds, the boy Jesus sowed also one measure of grain. And his father gathered 100 great measures and he gave it to the poor and the orphans. (trans. my own)

The same site is mentioned also by the sixth-century pilgrim Theodosius, who wrote: “From Jericho it is one mile to Gilgal: the Lord’s Field is there, where the Lord Jesus Christ ploughed a furrow with his own hand” (1; see also 18; trans. Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 63). The field seems to have been a fairly well-known site, but neither of these writers explicitly connect it with Jesus’ childhood years. Indeed, it could just as well commemorate a story from Jesus’ adulthood preserved in the unknown gospel of P. Egerton 2. The manuscript of this text is fragmentary, but it has recently been reconstructed by Lorne Zelyck, based in part on the pilgrimage accounts:

Then Jesus, as he walked, stood on the bank of the Jordan river; and reaching out his right hand, he took salt and scattered it upon the river. Then he poured out much water upon the ground. He prayed, and it was filled before them. Then it brought forth a crop of great abundance, produced by an everlasting gift for all these people. (Lorne R. Zelyck, The Egerton Gospel [Egerton Papyrus 2 + Papyrus Köln VI 255]: Introduction, Critical Edition, and Commentary, TENTS 13 [Leiden 2019], 83.)

Very few scholars have mentioned the pilgrimage accounts in connection to Infancy Thomas. The main exception is Bellarmino Bagatti, well-known for his archaeological work in Nazareth, but also frequently criticized for his uncritical use of literary sources about locations in Palestine, often considering locations of sites established in the Byzantine era to be genuine. In 1876 Bagatti wrote a short article aiming to prove that Infancy Thomas was written in Nazareth, in part because of the mention of the synagogue by the pilgrim. And Bagatti did find a building in the compound of the Basilica of the Annunication that he identified as a Jewish-Christian synagogue-church. Two late medieval writers, Peter the Deacon (De Locis sanctis) in the twelfth century and Burchard of Mount Sion (Descriptio Terrae Sanctae 6) in the thirteenth, also mention a synagogue that had become a church.

Though not mentioned by the early pilgrims, there are two other locations in Infancy Thomas that are commemorated even today in Nazareth. The first of these is Mary’s Well. A well or fountain is the site of the annunciation in the Protevangelium of James 11 (“And she took the water pitcher and went out and filled it with water,” 11:1; trans. Lily C. Vuong, The Protevangelium of James, Early Christian Apocrypha [Eugene, OR 2019]). Perhaps some association with this tradition is remembered in two churches built near the spring: the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation (also known as the Church of Saint Gabriel) and the Catholic Basilica of the Annunciation. The origins of both buildings, in their earliest forms, go back to the fourth century. Burchard of Mount Sion mentions the well in his description of the Holy Land (Descriptio Terrae Sanctae 6) as a place “venerated by the inhabitants, from which it is said the boy Jesus often drew water when serving His mother” (trans. Aubrey Stewart, Burchard of Mount Sion, PPTS 12 [London 1896]). Burchard may be recalling the story of Jesus Carries Water in His Cloak:

And the boy Jesus was about six years old and he was sent by his mother Mary to fill a water jar. But there was a great crowd at the water cistern, and the pitcher was jostled and broke. Then Jesus spread out the cloak he was wearing, filled it with water and brought it to his mother. And his mother was amazed and kept in her heart all she had seen. (Infancy Thomas 11; trans. Burke).

The well was in continuous use until 1966 but no longer functions; visitors today can see a reconstruction built in 2000. For more information, see this Wikipedia page.

The second Infancy Thomas location is Joseph’s workshop, commemorated by the Church of St. Joseph’s Workshop built in the Crusader era over a cave; it is not certain that its commemoration goes back any earlier. The workshop appears in the story of the Miraculous Repair of a Bed:

And he was about eight years old. And when his father, a carpenter, was making ploughs and yokes, he received a bed from a certain rich man so that he might make it exceedingly great and suitable. And since one of the required pieces was shorter and he did not have a measure, Joseph was distressed, not knowing what to do. The boy came to his father and said, “Put down the two pieces of wood and align them from your end.” Joseph did just as Jesus said to him. And the boy stood at the other end and took hold of the short piece of wood and stretched it. And he made it equal to the other piece of wood. And he said to his father, “Do not be distressed but do what you wish.” And Joseph embraced and kissed him saying, “Blessed am I for God gave me this boy.” (Infancy Thomas 13; trans. Burke)

The various pilgrimage accounts and the buildings that commemorate the early life of Jesus in Nazareth at best suggest that the Infancy Thomas stories were known in Palestine as early as the sixth century, though, again, the locations need not be derived from the text as they can be deduced from what one would expect of someone who called Nazareth home: a synagogue, a house, a well for water, and a workshop for a father known from the canonical Gospels as a carpenter. Nevertheless, someone with knowledge of Infancy Thomas, or perhaps its adaptation in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, could visit Nazareth, either in the past or today, and see a number of sites mentioned in the text. It could even function as a pilgrim’s guidebook to the town, moving participants from the synagogue of letters (chs. 6, 14, 15), to Mary’s Well (ch. 11), Joseph’s workshop (ch. 13), Jesus’ childhood home (14:3; 15:4), and imaginatively-assigned points between (the stream of ch. 2; the village street of ch. 4; the rooftop of ch. 9). The only limits are the guide’s imagination.

It is not a stretch to think that Infancy Thomas could be used to serve the pilgrimage trade. Other infancy apocrypha show an interest in pilgrimage, including the Vision of Theophilus and related traditions, which take the Holy Family on a tour of well-known pilgrimage sites in Egypt (for more discussion of these sites, see this earlier post), and the expanded version of the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which specifically places the story of the Miraculous Harvest in Jericho (chs. 34–35), perhaps showing awareness of the later tradition, and shows an interest in connecting other childhood stories to specific places (see the mention of Sohennen in 22:2 and the movements between Bethlehem, Nazareth, Capernaum, and Jericho in chs. 25–42).

Of course, none of this is evidence that Infancy Thomas was composed in Nazareth or nearby, nor that it was written to capitalize on the pilgrimage industry—it seems to have been composed too early for that—but that does not mean it could not be used for this purpose in later centuries, particularly given the popularity of pilgrimage and the interplay between apocrypha and pilgrimage that is observable in texts, architecture, and artifacts (for some examples, see this earlier post). The intersection of pilgrimage and apocrypha is one of my current research interests, so I was happy that the paper came around to this topic. I think pilgrimage should be taken into consideration when examining any of our texts—if not their creation then at least their circulation.