2019 SBL Diary: Day 3

My final full day in San Diego began with a meeting of the NASSCAL board—or at least those of us who made it to SBL (Janet Spittler, Lily Vuong, Lorne Zelyck, and Jonathan Henry)—to discuss plans for the next NASSCAL conference. These events take place, ideally, every two years; the last one was at the University of Virginia in 2018. Next year’s gathering will be at the University of Texas at Austin under the guidance of Brent Landau. For a theme we want something that is focused enough to give the conference an identity but open enough to encourage contributions from a wide range of specialties. So far we are looking at the theme of transformation—how apocryphal texts change over time through translation, expansion, contraction, adaptation, etc. We also quickly discussed planned volumes in the Early Christian Apocrypha series and the success of the e-Clavis (as Janet remarked, “I can’t believe how much we have done in just four years”).

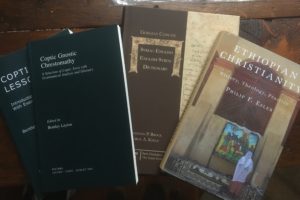

After the meeting I went back to the book display for a meeting with my editor at Yale University Press. I am working on a comprehensive overview of Christian apocrypha for the Anchor Bible series. The plan was to have it finished in two years—that was two years ago. Who would have thought a 600-page volume discussing over 300 texts would take longer? So, we negotiated a new deadline and I made promises to send some material along for review soon. Then I grabbed the last of my book purchases: Bentley Layton’s Coptic in 20 Lessons and Coptic Gnostic Chrestomathy (I am determined to learn Coptic this year!), Philip Esler’s Ethiopian Christianity, and a copy of George Kiraz’s Syriac Primer from Gorgias Press for one of my students along with two copies of the Gorgias Concise Syriac-English, English-Syriac Dictionary—it was buy two get one free at Gorgias, so I grabbed the second as a bonus for my student). The rest of my morning was “me time” with some walking around town and a quiet lunch.

After the meeting I went back to the book display for a meeting with my editor at Yale University Press. I am working on a comprehensive overview of Christian apocrypha for the Anchor Bible series. The plan was to have it finished in two years—that was two years ago. Who would have thought a 600-page volume discussing over 300 texts would take longer? So, we negotiated a new deadline and I made promises to send some material along for review soon. Then I grabbed the last of my book purchases: Bentley Layton’s Coptic in 20 Lessons and Coptic Gnostic Chrestomathy (I am determined to learn Coptic this year!), Philip Esler’s Ethiopian Christianity, and a copy of George Kiraz’s Syriac Primer from Gorgias Press for one of my students along with two copies of the Gorgias Concise Syriac-English, English-Syriac Dictionary—it was buy two get one free at Gorgias, so I grabbed the second as a bonus for my student). The rest of my morning was “me time” with some walking around town and a quiet lunch.

On the way back to the conference center I was stopped by a doctoral student (who will not be named). He had purchased some chocolate edibles and had too much to finish before heading home (it’s perfectly legal in California!). He offered some to me, saying he thought it would be “safe” to do so since we had discussed edibles in Denver (where I had my first experience with them). How could I say no? Just trying to help a student out.

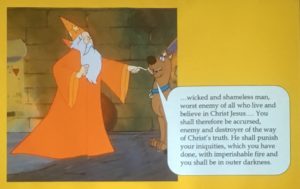

Now, back to work. My first session of the day was “Inventing Christianity: Apostolic Fathers, Apologists, and Martyrs.” It was not strictly a Christian apocrypha session but its theme of “Afterlives of the Apostles” drew in papers on several apocryphal acts and apocalypses. David L. Eastman (The McCallie School) began the session with “Pauline Primacy over Peter in the Apocryphal Acts.” Eastman has well-established himself as an expert on late antique acts of Paul and Peter (in Paul the Martyr: The Cult of the Apostle in the Latin West [2011] and The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul [2015]) but here he took a step back in time to focus on the earliest texts: the Acts of Peter and the Acts of Paul. Comparing the portrayals of the two apostles, he concluded that Acts Paul was written as a response to Acts Pet. to set Paul up as the primary figure of the Roman church. In Acts Paul, Paul is more authoritative in the presence of Nero, and whereas Peter tries to escape martyrdom, Paul declares “I am not a deserter.” Eastman devoted a large portion of his presentation to summarizing the texts, but he used some humorous images to keep the stories moving (some Scooby Doo stills when discussing the speaking dog in Acts Pet., and The Family Guy’s Stewie for the talking baby story). I was more interested in the Renaissance images he used of Simon’s death which work to minimize the tension between the two apostles by incorporating Paul into the event (Eastman called these “photo bombs”).

Now, back to work. My first session of the day was “Inventing Christianity: Apostolic Fathers, Apologists, and Martyrs.” It was not strictly a Christian apocrypha session but its theme of “Afterlives of the Apostles” drew in papers on several apocryphal acts and apocalypses. David L. Eastman (The McCallie School) began the session with “Pauline Primacy over Peter in the Apocryphal Acts.” Eastman has well-established himself as an expert on late antique acts of Paul and Peter (in Paul the Martyr: The Cult of the Apostle in the Latin West [2011] and The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul [2015]) but here he took a step back in time to focus on the earliest texts: the Acts of Peter and the Acts of Paul. Comparing the portrayals of the two apostles, he concluded that Acts Paul was written as a response to Acts Pet. to set Paul up as the primary figure of the Roman church. In Acts Paul, Paul is more authoritative in the presence of Nero, and whereas Peter tries to escape martyrdom, Paul declares “I am not a deserter.” Eastman devoted a large portion of his presentation to summarizing the texts, but he used some humorous images to keep the stories moving (some Scooby Doo stills when discussing the speaking dog in Acts Pet., and The Family Guy’s Stewie for the talking baby story). I was more interested in the Renaissance images he used of Simon’s death which work to minimize the tension between the two apostles by incorporating Paul into the event (Eastman called these “photo bombs”).

The Acts of Paul alone was the focus of fellow Canadian Carly Daniel-Hughes’ (Concordia University – Université Concordia) paper, “Satirizing the Apostle: A Rereading of Gender and Desire in the Acts of Paul and Thecla.” Daniel-Hughes offered a corrective to the usual assessment of the Acts as authorization for a life of chastity. There are observable tensions on the issue of asceticism in the text, as well as between the text and the canonical Corinthian correspondence on which it draws (e.g., the “weak” Paul in 2 Cor 10:10 and 11:30 may relate to the description of Paul in Acts Paul; 1 Cor is invoked in the beatitudes). Daniel-Hughes argued that the text’s erotic elements—Thecla’s yearning for Paul, the prurient interest in Thecla’s nakedness—and negative depiction of Paul—he frequently abandons Thecla—suggest that Paul is not so much an authority in this text as a caricature.

A second set of papers in the session again examined Peter and Paul, but this time as sojourners in hell. Meira Z. Kensky (Coe College) began with “Go to Hell: Vicarious Travel with Peter in the Apocalypse of Peter.” I met Kensky the day before at the University of Virginia reception. We both have an interest in the intersection of apocrypha and pilgrimage (see her paper on the Acts of Timothy in the Perkins volume, mentioned below). In my own work on pilgrimage for the Material Apocrypha conference last year, it never occurred to me to think of tour-of-hell apocalypses as travel narratives. But Kensky made a persuasive argument for texts like Apoc. Pet. functioning as a vicarious pilgrimage in which the reader journeys with the visionary and returns “home” having learned about justice, correct moral behavior, and compassion. Kensky placed Apoc. Pet. also in the growing body of travel literature of its time, not only to real places, such as Pausanius’s Description of Greece, but also to fictional lands. The Peter-Paul rivalry returned in Sara A. Misgen’s (Yale University) “Characterizing Apostles: Narrative Agency in the Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of Paul.” Misgen highlighted the different portrayals of the two apostles in their apocalypses: Peter speaks little and is rebuked by Jesus, whereas Paul is far more “chatty” and successfully argues for a respite for sinners every Sunday. The differences, Misgen said, are due in part to the canonical points of departure for both figures: Apoc. Pet. begins at the Transfiguration and Apoc. Paul from the apostle’s account of his journey to the heavens in 2 Cor. Misgen rightfully cautions also that Apoc. Pet. is closer to the genre of Greco-Roman tours of hell and though Apoc. Paul uses Apoc. Pet. for inspiration, the Christian tours of hell take on a number of different characteristics by its time of composition. Even though, as Eastman demonstrated, the two apostles often are portrayed in competition, transformations in the genre seem to be the reason for the differences in their depictions here; however, it should be remembered that Apoc. Paul essentially “replaced” Apoc. Pet. in the West.

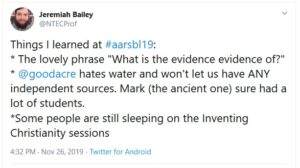

The final paper in the session was another look at the Shepherd of Hermas (there seems to be a surge in interest in this text lately). In “The Afterlives of the Apostles and the Apostolic Role of Hermas’s Shepherd,” Jonathan E. Soyars (Louisville Seminary) noted that while the role of apostle is praised in the text, no apostles are mentioned by name. He argued that Hermas takes over the function of apostle, proclaiming the gospel and being a model of virtue, though he never calls himself one. Naming other apostles, Soyars said, would interfere with Hermas’ assertion that the office continues through him. The “afterlives” of the apostles in this text, then, are absent, their legacies usurped by a figure of legend. I noticed a day after the session that Jeremiah Bailey (PhD candidate, Baylor University) on Twitter joked about people sleeping at this session. I hope he didn’t see that as a reflection of the papers; it was right after lunch after all. And if he meant me: I was just resting my eyes!

The final paper in the session was another look at the Shepherd of Hermas (there seems to be a surge in interest in this text lately). In “The Afterlives of the Apostles and the Apostolic Role of Hermas’s Shepherd,” Jonathan E. Soyars (Louisville Seminary) noted that while the role of apostle is praised in the text, no apostles are mentioned by name. He argued that Hermas takes over the function of apostle, proclaiming the gospel and being a model of virtue, though he never calls himself one. Naming other apostles, Soyars said, would interfere with Hermas’ assertion that the office continues through him. The “afterlives” of the apostles in this text, then, are absent, their legacies usurped by a figure of legend. I noticed a day after the session that Jeremiah Bailey (PhD candidate, Baylor University) on Twitter joked about people sleeping at this session. I hope he didn’t see that as a reflection of the papers; it was right after lunch after all. And if he meant me: I was just resting my eyes!

The final session of the day, and for the entire conference, was for the Christian Apocrypha Section with five papers on the theme “Narratives and Motifs in the Christian Apocrypha” (so, basically an open session). Ally Kateusz (Wjingaards Institute of Catholic Research) began with “Debunking lectio brevior potior as a Rule of Thumb for Reading Early Christian Narratives about Women Leaders.” Kateusz works primarily on the early Dormition of the Virgin accounts and has received some attention for her work online recently (including an interview on the Bible and Beyond podcast). Her argument is that evidence for the leadership of women in early Christian groups has been obscured both in the transmission of Christian literature and by scholars who work on it. This paper focused on the criticism that longer readings in the texts, such as those that champion women’s leadership, are more likely to be added in the tradition than removed. However, Kateusz demonstrated effectively for one reading that scribes of two later witnesses excised different sections of a longer text. The principle of lectio brevio potior cannot be applied too rigorously; both expansion and abbreviation occur in apocryphal texts—consider the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, which begins as a 14-chapter text (the early versions), adds two more episodes (Greek S recension), then another three (Greek A), then divides into both longer (Greek C) and shorter (Greek B) forms. Also, it seems to be that lectio difficilior (he more difficult reading) should trump lectio brevior when it comes heretical ideas and practices.

Kateusz expanded her argument to include several other texts, including Acts of Thecla, which she suggested was an abridgement of the larger Life of Thecla. Fellow panelist Jenna Whalley-Kokot (Boston College) took issue with this position, leading to a lively exchange about the relationship of the Thecla materials to the Acts of Paul. Whalley-Kokot’s own paper, “A Living Martyr: Martyrdom Motifs and Baptism of Blood in the Greek Acts of Thelca,” presented a really interesting argument about Thecla’s self-baptism—namely, that it should be understood in the context of martyrdom as a baptism of blood for those who did not have a valid water baptism. Part of her argument was that self-baptism does not occur elsewhere in Christian literature (even the verb in a passive form is rare). And the fact that Thecla survived her ordeal does not negate the possibility of a baptism of blood (she certainly expected to die). There is ambiguity also about what being a martyr (“witness”) meant in the second century—indeed, as I mentioned in the session, the term retains ambiguity in even later apocrypha, such as the Martyrdom of Cornelius, in which Cornelius dies a peaceful death (so here either “martyr” should be considered literally as a witness to the faith or the text is evidence for a loose practice of equating “saint” with “martyr”).

Two other papers in the session dealt with the theme of gender. The first was Carl Johan Berglund’s (Uppsala University) “Discipleship Ideals in the Apocryphal Acts: A Radical Departure from the Gospels?” The most interesting section of Berghund’s presentation focused on the Acts of Philip, which features the male-female evangelizing team of Philip and his sister Mariamne. The two display sensibilities that transcend typical gender boundaries: Mariamne is praised for having the strength of a man, whereas Philip exhibits the will of a woman. After the paper, Kateusz pointed out that the text is a prime example of expanded roles for women in the early centuries: Philip preaches to men and Mariamne wot women, and the hell episode (1:12) mentions male and female priests—and I would add, in Parthia, Philip is accompanied by “some women who were imitating the male faith” (2:1). The other gender related paper was by Justin M. Glessner (DePauw University), who presented in 2018 on Joseph in the Protevangelium of James. This year he turned his attention to Inf. Gos. Thom. in “Who’s ‘Your Hegemon’ (Paidika 4.1)?! Joseph in the Paidika.” Glessner pointed out that few studies of the text have looked closely at Joseph’s role. In the episodes that feature Joseph prominently, he attempts to play his role as dominus to punish or correct the behavior of his unruly son, and to try to educate or train him. Frustrated in his attempts, Joseph becomes frustrated, whereas Jesus displays a masculine mastery of the self. In the end, Joseph is not a bad father—how can he be expected to control a boy like this, who is more than human? Given my work on this text, my friends at the session were expecting me to respond to Glessner, and perhaps he was hoping (or dreading I would too), but I thought his paper was good—I had nothing to ask about or object to! But I probably could have said something encouraging, and I did speak to him during the break about aspects of the text that we agreed on.

The remaining paper in the session was by Stephanie Janz (Universität Zürich), a graduate student working on the Gospel of Thomas. Her paper “Mary and the Gospel of Thomas: A Narratological Perspective” focused on log. 114, the exchange between Peter and Jesus over Mary’s status in the group, and log. 21, Mary’s question on discipleship. Janz used these two logia as a test case for determining if one can use narrative criticism to better understand the text, rather than dwelling on which saying or other is original to the text. To some extent this approach can be fruitful—I frequently use log. 22 (“make the male and the female be a single one”) to help explain log. 114—and certainly the text is replete with catchwords and recurring themes. But this approach really only works on the form of the text that is preserved in a single fourth-century Coptic codex. So until our evidence for Gos. Thom. expands, the results really only tell us about the environment of this one form of the text (though that is important too).

The plan for the evening was to attend the Wipf & Stock reception. It’s typically considered the place to be, particularly for the free food and drinks (clearly this is my motivation). The reception was held in a packed downtown bar. I spent most of time cocooned with my fellow Canadians once again but I ran into some familiar faces, including Stephen Shoemaker and James McGrath. I popped in my edible early in the night but never really felt its effects (at least that I can recall). Was I duped? Several of us moved on to the Bloomsbury reception, as it is usually a hopping event, but by the time we arrived, the open bar had ended and people were dispersing. So this seemed as good a time as any to call it a night.

My plan for Tuesday was to attend the final Christian Apocrypha Section session (partnered with Ancient Fiction and Early Christian and Jewish Narrative) featuring papers from The Narrative Self, a volume edited by Janet Spittler in honor of Judith Perkins (read more about the book HERE). Unfortunately, I hadn’t realized that my flight was too early to stay for very long, so I headed off to the airport, sharing a cab with a few friends. The flight home was uneventful—no security hassles, no delays—and I got into Hamilton at 1 am. All-in-all, the 2019 SBL was professionally and personally rewarding—though I had fewer meetings than usual and some friends did not make it out this year. I’ve been weighed down lately by the frustrations of administrative work (I am program coordinator trying to revamp our curriculum and create events for students and faculty; if you think that editing is like “herding cats,” try administration) and by family crises (teenagers, am I right?). But five days of San Diego weather and surprising amount of solid sleep (I love you, sleeping pills), as well as the company of friends, and I came home feeling re-invigorated.

See you next year in Boston (Boston? Why can’t it be in San Diego every year?).