“Acts” of John and Philip in the Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae

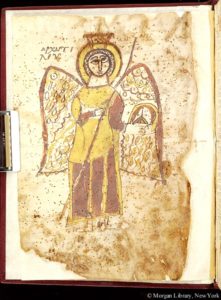

The Archangel Michael is one of the most important of the Christian saints—second only to the Virgin Mary in prominence in late antique and medieval Christianity, both in the East and the West. Holy sites dedicated to the saint are spread out all over the Christian world; one of the most prominent is the island of Mont St. Michel in Normandy, built in the eighth century. Pilgrims would come to these sites for healing, typically from contact with a spring or fountain—given that the saint was incorporeal, contact with relics was not an option. Such veneration of Michael is surprising given that the New Testament forbids angel worship (Col 2:18; Rev 22:8-9).

Michael rarely appears in canonical texts (see Dan 10:13, 21 and 12:1; Jude 9; Rev 12:7-9) but he is prominent in apocryphal texts, particularly tour-of-hell apocalypses, where he is depicted as interceding with God on behalf of humans. The most lengthy of the Michael apocrypha is the Coptic Investiture of the Archangel Michael, in which the risen Jesus tells his apostles about the creation of the angels and the fall of humanity, and the Encomium on the Archangel Michael, in which Prochorus, the disciple of John, relates Michael’s explaination to him about how he annually rescues sinners from damnation. Similar material is related in a Greek text known as the Homily of John Chrysostom on How Archangel Michael Defeated Satanail. But there is another Michael text that does not get included in discussions of apocrypha, one that intersects with apocryphal acts because it features “acts” of two apostles: Philip and John.

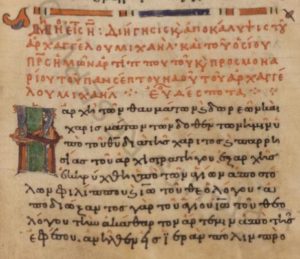

The Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae is extant in three Greek versions (BHG 1282–1284), one in Latin (BHL 5947), and another in Ethiopic (BHO 759). The first Greek recension (BHG 1282) is attributed to the hermit Archippos and was published by Max Bonnet (“Naratio de miraculo a Michaele archangelo Chonis patrato,” AnBoll 8 [1899]: 287–328, at 289–307 [Greek text], 317–22 [Latin trans.]); the second (BHG 1283), attributed to Sissinius, can be found in Acta Sanctorum, Septembris 8:14–47; and the third (BHG 1284), attributed to Simeon Metaphrastes, was again published by Bonnet (ibid., 308–16 [Greek text], 323–28 [Latin trans.]). As for the Latin, only the prologue to the Latin text has been published so far (“Nota Miraculum A. S. Michaele Chonis Patratum,” AnBoll 9 [1890]: 201–203) and the Ethiopic appears in Johannes Bachmann, Aethiopische Lesestücke (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1893), pp. 20–23. Pinakes lists 87 manuscripts of the Greek recensions; the earliest of these is Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, suppl. gr. 480, a palimpsest dated to the eighth century. To my knowledge, the text has not been translated into a modern language.

Scholars of the text divide its transmission history into two stages (the following summary is paraphrased from Arnold, Footprints of Michael the Archangel, 43–44). The first comprises chs. 1–3, composed in the fourth century. The introduction, which features Philip and John, is as follows (my translation):

The beginning of the healings and the gifts and the favors that God has granted to us by the grace and assurance of the Archistrategos Michael, proclaimed from the beginning by the holy apostles Philip and John the Theologian. For after the holy John chased away the impure Artemis from Ephesus, he went up to Hierapolis to holy Philip, for he was at war with a viper. And having greeted each other, the holy Philip said to him, “What can we do, brother John? Because I am not able to uproot this impure and foul [viper] from this city.” For this foul and destructive viper was the leader of all creeping and impure things. And its entire body was surrounded by snakes, and a dragon curled around its head and another curled around its neck. And it was standing upon two dragons, and curled around it everything creeping <and> impure, and adorned, to speak generously, like a queen. And the Greeks considered it a great goddess and all paid homage to it and sacrificed to it. Often when the holy Philip was sitting and teaching, it allowed the creeping things to run about upon the holy one in order to kill him. And he (John) said to him: “Come out, Philip, before the misery of this city consumes you.” And the holy Philip was proclaiming the word of truth and faith. And the apostles prayed and cast out it out from Hierapolis.

After this the venerable heralds of truth came and stopped in a place called Chairetopa, grace and gifts and wonders were about to be manifested there by the holy and revered Archistrategos Michael. And after praying they indicated to the people saying that the great Taxiarch and Archistrategos of the power of the Lord is about to arrive here and accomplish incredible wonders. Then the apostles departed, teaching to other cities. And immediately healing water sprang up in that place.

Readers of the apocryphal acts will recognize here a reference to John’s destruction of the temple of Artemis in Acts of John 37–55 and, generally, to John’s activities in Ephesus as told also in the Syriac History of John and the Acts of John by Prochorus. The story of Philip’s combat with the viper cult of Hierapolis is told in Acts of Philip 13 but John does not appear until Acts Phil. 15, just as Philip is about to be martyred. The goal of the original, shorter text is to provide a backstory to the holy site at Chairetopa, one that reaches back to apostolic times.

Chairetopa (modern Ceretapa in Turkey) perhaps was not originally a village but received its name because it is a “place” (topos) to “greet” (chaire) the angel. The story goes on to tell what happens after the apostles leave the town. One day, a non-believer from Laodicea comes to Chairetopa. Michael appears to him in a dream and tells him to bring his mute daughter to the spring. When they arrive, they find others there calling upon “the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit and Michael the Archistrategos.” The man scoops up water and puts it in his daughter’s mouth and she is able to speak again.

In the following eight chapters, added around the eighth century, the activity moves to nearby Chonae in Phrygia, perhaps because over time it became the dominant pilgrimage site for Michael in the area. According to the story, a hermit named Archippos was being persecuted by non-believers who wanted to destroy an oratory dedicated to Michael by diverting waters to submerge the site. Archippos prayed to the angel and in response he split the rock, forcing the waters to funnel (in Greek: chon?) into the ground. Chonae remained a major pilgrimage site until the thirteenth century and the miracle is commemorated still today on September 6.

The Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae presents a problem for apocrypha scholars. It features some apocryphal traditions, but perhaps not enough to classify the text as an apocryphon, and thus it has gone largely unnoticed in the field. Nevertheless, it should be useful to those interested in the apocryphal acts, particularly the texts that feature John and Philip, and for those interested in the intersection of apocrypha and pilgrimage.

For more on the Miracle of St. Michael the Archangel at Chonae see:

Arnold, John Charles. The Footprints of Michael the archangel: The Formation and Diffusion of a Saintly Cult, c. 300–800. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Johnson, Richard F. Saint Michael the Archangel in Medieval English Legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005.

Peers, Glenn. “Apprehending the Archangel Michael: Hagiographic Methods.” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 20 (1996): 100–21.

Peers, Glenn. Subtle Bodies, Representing Angels in Byzantium. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.