Reconstructing a Ninth-Century Arabic Apocrypha Manuscript from Mount Sinai

Though I have a number of important projects in progress at the moment, sometimes I throw them aside for a day or two while I chase down some information about an apocryphal text or manuscript. Yesterday was one of those days. So I don’t lose track of what I’ve learned, I thought I would compile it all in a blog post—and since my last blog pose was in February, I can justify this diversion as necessary for maintaining my social media presence, right?

My morning began by posting the latest entry in NASSCAL’s e-Clavis: the Six-Books Dormition of the Virgin, compiled for us by Alley Kateusz. The 6 Bks. Dorm. is extant in Syriac (CANT 123 and 124), Arabic (140), and Ethiopic (150). The Arabic text was published from a manuscript in Bonn in 1854 by Maximilian Enger (Ionnis Apostoli de Transitu Beatae Mariae Virginis Liber). Enger’s edition includes also a Latin translation, which was translated into French a few years later in Jacques-Paul Migne’s Dictionnaire des Apocryphes. Enger’s text was reprinted in Pilar González Casado’s doctoral thesis (“Las relaciones linguisticas entre el siriaco y el arabe en textos religiosos arabes cristianos”; Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2013) along with a Spanish translation. So, what is the problem that I needed to solve? Casado states in her introduction that Enger’s source is a ninth-century manuscript from Bryn Mawr College Library (p. 6), but later correctly identifies the source as the manuscript from Bonn (p. 181).

What is this mysterious Bryn Mawr manuscript? I had to know.

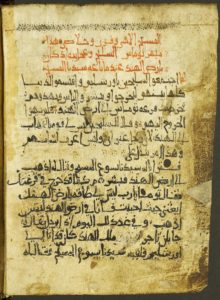

Alley pointed me to Simon Mimouni’s Dormition et assomption de Marie, which was published in 1995, years before the completion of Casado’s thesis. Mimouni does not seem to have consulted the manuscript, but he did leave a trail to follow for discovering more about it. The earliest reference is found in an article (“Alte christlich-arabische Fragmente”; OrChr NS 4: 338–41) by Georg Graf in 1915. The antiquarian Ludwig Rosenthal (1840–1928) asked him to examine a manuscript and determine its age and contents. Graf revealed that it was from Mount Sinai and copied in the ninth century by a monk named Thomas. The first few pages provide a table of contents listing 22 texts, including several apocryphal works: the Dormition of the Virgin (6 Bks. version), the Story of the Apostles Peter and John and Their Instructions to the Antiochians (apparently the same text as the Story of Peter and Paul in Antioch from Sinai Arab. 539 and elsewhere), the Story of the Apostle Peter When He Arrived in Rome and His Instruction to the Romans (identification uncertain; CANT 202?), the Invention of the Cross, the History of Philip (CANT 253), and the Acts of Thomas (CANT 245). The colophon (fol. 2) states that “no one has the authority to remove it from the church,” and includes a book curse: “whoever removes it will be under [the displeasure of ?] the Eternal Word.”

Unfortunately, the materials owned by Rosenthal comprised only 52 folios: most of 6-Bks. Dorm. and the beginning of the Invention of the Cross. After folio 38 are inserted eight folios from another manuscript containing Martyrdoms of Anba Quris and Yuhanna, and of the Three Virgins (Thawuqtisti, Thawuzuta, and Udhaqsiyah) and their mother Arthanasiyah. And inside the cover are two folios from yet another manuscript preserving portions of six mimars of Joseph of Serugh.

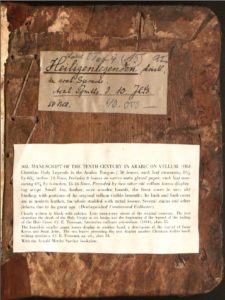

We hear of the manuscript again in 1922 in bookseller Karl W. Hiersemann’s Katalog 500. Orientalische Manuskripte…des 7–18 Jahrhunderts (Leipzig), which lists 53 manuscripts for sale originally from St. Catherine’s Monastery. One of the manuscripts, no. 15 (p. 12) was the manuscript seen by Graf. It is followed by no. 16 (p. 12–13), which, apparently unbeknownst to Anton Baumstark, who provided the descriptions for these two pieces, was another 117 folios of the same manuscript, containing, among other items, the pages from Acts Thom. The Katalog also includes two images: pl. 7 is a page from no. 15 and pl. 8 from no. 16. Further detective work on the fate of these manuscripts by Bernard Outtier (“Le sort des manuscrits du Katalog Hiersemann 500,” AnBoll 93 [1975]: 377–80) and Werner Strothmann (“Die orientalischen Handschriften der Sammlung Mettler (Katalog Hiersemann 500),” ZDMG Supplement 2.1 [1975]: 285–93) reveals that they were purchased by Arnold Mettler-Specker, who loaned his collection to the Zentralbibliothek of Zurich, where they were cataloged as Or. 74 (no. 15) and Or. 75 (no. 16).

At his death in 1945, Mettler-Specker’s collection was put up for sale through the Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York (see p. 102 and 107 of the Parke-Bernet Galleries 1948 catalog). No. 15 was purchased by Howard Lehman Goodhart and, after his death in 1951, the manuscript was donated to Bryn Mawr College Library, cataloged simply as “Legends of the Saints” (see James W. Pollock, “Two Christian Arabic Manuscripts in the Bryn Mawr Library,” JAOS 110.2 [1990]: 330–31). No. 16 was purchased by the Universitätsbibliothek Leiden, where it still resides as Or. 14.238.

The next chapter in this saga was written by Michel van Esbroeck in “Remembrement d’un manuscrit sinaitique arabe de 950” (pp. 136–47 in Actes du premier Congrès international d’études arabes chrétiennes; ed. Kh. Samir; OCA 218; Rome 1982). He restated the history of the two Hiersemann manuscripts and discusses also a third portion of the same manuscript, mentioned first in “l’annexe du catalogue 500” (whatever that means; I have not been able to find this reference) by Baumstark, who describes it as a codex of 12 folios containing portions of the Invention of the Cross, Acts Thom., and Hist. Phil. Baumstark recognized the folios as part of Hiersemann 15. They were purchased by Selly Oak College in Birmingham, where they are cataloged as Christ. Arab. 94 (11 fols.) and Add. Arab. 148 (1 fol.). Mingana’s catalog of the collection (Catalog of the Mingana Collection of Manuscripts; 3 vols.; 1936–1939) notes that a third fragment, Add. Arab. 149 (4 fols. containing more portions of the Invention of the Cross and Hist. Phil.), belongs to the same manuscript. A fourth fragment, Add. Arab. 130 (1 fol. containing a portion of 6 Bks. Dorm.), is included in the catalog but its affinities with the other fragments is not recognized; Graf (Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, vol. 3, p. 251) mentions the manuscript in his discussion of Arabic Dormition texts, including Hiersemann No. 15, but also does not recognize their relationship. Van Esbroeck’s article assembles all of this evidence and reconstructs the remaining portions of the manuscript, which now totals 176 fols. of what was originally approximately 400 fols. The results, with some corrections from my own examination of the manuscripts, are as follows:

B=Bryn Mawr; M=Mingana; L=Leiden

Quire 1: B fols. 3r–4v (contents); M 130 fol. 1 (beginning of 6 Bks. Dorm.); B fols. 4v–10r (6 Bks. Dorm.)

Quires 2–5: B fols. 10v–40v (ending of 6 Bks. Dorm.)

Quires 6–10: missing

Quire 11: B fol. 49r half page with ending of the Story of Peter; B fol. 50v–53v beginning of the Invention of the Cross

Quire 12: 2 missing folios; M 94 fol. 1; M 149 fol. 1; M 94 fols. 2–3; one missing folio (all from the Invention of the Cross)

Quire 13: M 94, fol. 4 (end Invention of the Cross; then follows an excerpt of Epiphanius on the Virgin and the beginning of Hist. Phil.); M 149 fols. 2–4; M 94 fols. 5–11; M 148 (Acts Thom. begins M 94 fol. 8v)

Quires 14–28: L fols. 1–120 (Acts Thom. concludes at ch. 65 on fol. 22v; then follow martyrdoms up to the Life of Saint Euthymios; remaining texts lost)

Van Esbroeck returned to the manuscript in 1987 with an edition and French translation of its version of Acts Thom. (“Les Actes Apocryphes de Thomas en version arabe,” ParOr 14 [1987]: 1–77). I got my own look at the Bryn Mawr portion of the manuscript (now cataloged as BV 69) thanks to Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts. At present there are plans to make the digital files accessible as part of the Muslim World project (information HERE); in the meantime, Hansen is happy to share the images with any scholar who is interested in seeing them. It is certainly a valuable manuscript, not least because of its antiquity—for a while it was the earliest known source for the Acts of Thomas in any language and it predates Enger’s manuscript of 6 Bks. Dorm. by nine centuries.

For more on the manuscript, see NASSCAL’s Manuscripta apocryphorum page, which includes links to images from Mingana Christ. Arab. 94.