The Stoning of the Devil (Ramy al-Jamarat) in Coptic Christian Apocrypha

Two Coptic Christian texts to be included in the second volume of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures (edited by me and Brent Landau) allude, perhaps, to the Ramy al-Jamarat, a ritual performed by Muslims during the Hajj pilgrimage that involves throwing stones at the devil. If indeed the writers of these Christian apocrypha are aware of the ritual, then these texts illustrate Muslim-Christian interaction in Egypt and perhaps open up questions about pre-Islamic origins of the ritual.

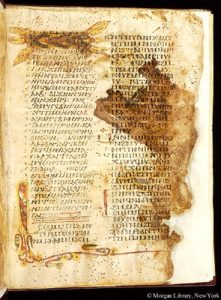

The longest version of the account appears in a fragmentary text sometimes referred to as the Homily on the Life of Jesus and His Love for the Apostles. Some scholars believe the lost beginning includes an attribution to Evodius, the successor of Peter as bishop of Antioch, but in Coptic Christianity he is considered the second bishop of Rome. The text has been reconstructed on the basis of three manuscripts, all dated to the tenth century and deriving from the White Monastery. Today the pages of these manuscripts are dispersed among various European collections. Timothy Pettipiece has prepared a translation for MNTA 2, the first complete translation of the text in English. The text retells certain stories from the Gospels—the multiplication of the loaves and fishes, the raising of Lazarus, and Peter’s confession at Caesarea Philippi—but with significant expansions. Between these stories are weaved three new episodes: an effort to make Jesus king of Judea (inspired by John 6:15), the apostles’ encounter with the devil and his demons disguised as fishermen, and a truncated dialogue with Bartholomew.

The relevant portion of the text comes in the story of the devil and his demons. Jesus and the disciples are walking along and the evil and his demons appear, dressed like fishermen and casting their nets upon the mountain. The implication is that the devil will snare solitudes in the desert and would-be monastics must be wary of him. John steps forward and challenges the devil. The author writes,

Then Saint John went to the devil. He said to him, “What are you doing with these nets and what do you catch in this place?” The devil replied, “I heard it said about you and your brothers that you are fishers, men who catch fish. I came here to see your master today. Here I am in this place, me, my servants, and my nets. Call your brothers too, so that they join you here with their nets, and let us cast them in this place. The one who can catch fish in this place is the master. It is no miracle to catch fish in the water. The miracle is to catch them in the desert.”

John said to him, “I too have heard talk of your mastery before I even joined you here. But cast your nets and we will see what you catch.” He cast them on the ground and caught all sorts of foul fish that are in the water. Some were caught by the eyes, others by the belly, still others by the lips.

Jesus was further away with his apostles and observed. He said to them, “See how Satan captures sinners by their limbs.”

Jesus said to John, “Tell him to cast (61) his net again.” John went to him a second time and said, “We have seen this mastery of yours. Cast your nets again, that we may see you.”

Then he cast them again on the mountain and a great smoke appeared. Immediately the devil understood and his power disappeared. He said to John, “Is this your mastery?” John replied to him, “The master is Christ. The one who makes empty all mastery like yours, which is that of a tempter.”

Then my father John took a stone and threw it at him and struck him. He fled full of shame and uttering curses. The apostles were amazed by his arrogance. (17:9-15)

The story is recalled in the second text, the Investiture of the Archangel Michael, translated for MNTA 2 by Hugo Lundhaug. The text is found in three Coptic manuscripts—two from the ninth century originating from the Monastery of the Archangel Michael at Phantoou in the Fayum, and the third is a ninth- to eleventh-century fragment from the White Monastery near Sohag. The text is found also in a small Greek fragment from Serra East in Lower Nubia, and an Old Nubian fragment discovered at Qasr Ibrim. Invest. Mich. is structured as a sequence of questions posed by the apostles to the risen Jesus. Much space is devoted to teachings about the fall of the devil and the investiture of Michael the Archangel in his place. The relevant section of the text for the stoning ritual is chapter 11. The episode begins with Jesus and his apostles mounting an olive tree and flying off for a tour of hell. The “little disciples”—followers of the apostles—are left behind and, offended at being excluded, they decide to return to their homes. The devil then appears to them in the appearance of an apostle and encourages them in their decision to leave. Then Berberos, the disciple of John, speaks up and tells them a story:

My brothers, let us not speak like this, for there is no favoritism before God. For I remember a day when our Lord told them to throw stones at the devil. They came and they all threw stones at him. No stone hit him except the stone of my father John. So that one, now, who speaks with you, turns your hearts. Arise and pray together and our Lord will give us strength. (11:13-16)

The little apostles pray and the devil disappears.

How is this story reflected in Islamic ritual? The stoning of the devil is reminiscent of the Ramy al Jamarat (“stoning of the place of pebbles”), a ritual performed at the annual Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca (for a quick overview of the ritual, visit the Wikipedia page). It is a re-enactment of an episode in the life of Abraham. The story is told by the Muslim historian al-Azraqi:

When he [Abraham] left Mina and was brought down to (the defile called) al-Aqaba, the Devil appeared to him at Stone-Heap of the Defile. Gabriel (Jibrayil) said to him: “Pelt him!” so Abraham threw seven stones at him so that he disappeared from him. Then he appeared to him at the Middle Stone-Heap. Gabriel said to him: “Pelt him!” so he pelted him with seven stones so that he disappeared from him. Then he appeared to him at the Little Stone-Heap. Gabriel said to him: “Pelt him!” so he pelted him with seven stones like the little stones for throwing with a sling. So the Devil withdrew from him. (from F.E. Peters, A Reader on Classical Islam [Princeton University Press, 1994]).

Another account adds the detail that Satan was trying to stop Abraham from fulfilling God’s command to sacrifice Ishmael. And other hadiths say that Adam was the first person who threw pebbles at Satan. In the Hajj pilgrimage, participants stone three walls (formerly pillars) that signify the temptation to disobey God and preserve Ishmael. It is not known when this tradition began, though Muslims claim that it was part of pilgrimage rituals before Muhammad and that his uncle Abu Talib mentions the practice in one of his poems.

What are the implications of this parallel? It is possible that throwing stones at the devil, or demonic figures, is a sufficiently widespread practice in Eastern religions that the use of the motif in Islam and Christianity is not particularly significant. The Coptic texts are believed generally to have been composed around the fifth century, which suggests a pre-Islamic context for the story, but the manuscripts provide a terminus ante quem of at least the ninth century, so the story could have been added at any point in the intervening centuries, and perhaps from contact with Islam. Invest. Mich. includes other material indicative of contact with Islam: its account of the fall of the devil shares features with several passages from the Qur’an (as well as two other Coptic texts: the Investiture of Abbaton, and the Investiture of Gabriel).

As far as I am aware, the Christian account of the John’s stoning of the devil has not been drawn previously into discussion of Muslim-Christian interaction, likely because the texts are not widely known. Their inclusion in MNTA 2 will help bring much-needed attention to this material. As Lundhaug states in his introduction to Invest. Mich., “In light of the preserved Coptic manuscripts’ production and use in Christian monasteries situated within Islamic Egypt, such parallels between the Islamic and Christian traditions are instructive, as well as indicative of a kind of cultural transfer that is ripe for closer scrutiny.”

To the best of your knowledge, is Satan exclusively referred to as “Satan” in Coptic Christian apocryphal texts? Is he ever referred to as “Iblis”?

One further question I am entertaining is if and how the function of “stoning” differs in any meaningful sense between the Christian and Islamic contexts. Is it more literal in one and therefore more symbolic in the other?

Personally, I only know an Iblisic context. In it lies an imputation to harden oneself in the face of estrangement, as urged on by Iblis himself.

https://iblisism.blogspot.com/p/harden-heart-in-isolation.html