2018 New Testament Apocrypha Course: Week 9

This week marked our final look at ancient Christian-authored apocrypha; our final class, in two weeks, focuses on anti-Christian apocrypha (the Toledot Yeshu and the Gospel of Barnabas) and, newly added this year, modern apocrypha. But this week we looked at tales of Mary, Joseph, John the Baptist, and Jesus’ wife Mary Magdalene (just joking).

Again, as a result of York’s labour disruption, I created a video lecture for this week’s class (which you can view HERE, if you wish). I began with a discussion of references to the family of Jesus in patristic literature: the names of Jesus’ sisters according to Epiphanius, traditions about the death of James, and Hegesippus (via Eusebius) on the grandsons of Jude and Jesus’ cousin Symeon, who took over the office of bishop of Jerusalem after the death of James.

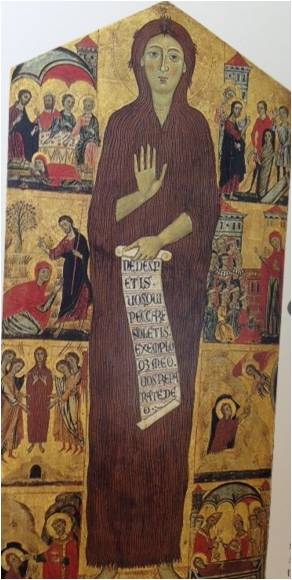

I turned next to the Marian apocrypha, beginning with a discussion of Stephen Shoemaker’s paper, “Rethinking the ‘Gnostic Mary’: Mary of Nazareth and Mary of Magdala in Early Christian Tradition” (JECS 9.4 [2001]: 555-95), in which he argues that there is much assimilation and confusion of the various Marys in apocryphal Christian traditions. Shoemaker focuses on two of these Marys, but I discussed also Mary of Bethany and the “other Mary” (=Mary, mother of James?) at the tomb, all of which are combined in various ways in the texts. This is demonstrated in the Life of Mary Magdalene, a late-antique text from an unpublished Greek manuscript and in a Latin form incorporated in the Golden Legend. Here Mary Magdalene is identified as Mary of Bethany and Luke’s sinful woman (Luke 7:36-50); Martha, surprisingly, is said to be the woman with a hemorrhage (Mark 5:21-43 par.).

After a survey of the Life of Mary and a few other Marian texts (Epiphanius’ suspicious descriptions of the Questions of Mary and the Genna Marias), I moved next to the Dormition of Mary. The students were assigned the late fifth-century version of the text attributed to St. John the Theologian, which, though not representative of the earliest traditions (the Syriac and the Ethiopic) was nevertheless very popular and is much more accessible (lamentably, the Dormition texts are rarely included in the English apocrypha collections; J. K. Elliott’s The Apocryphal New Testament has versions in Latin and Greek, but not the Syriac and Ethiopic). In our online chat this week, the students remarked that the Dormition was useful for bringing a sense of closure about the fate of Mary, who is not mentioned in the NT at all after Acts 1:14. They could see, however, that some Christians throughout the centuries may have felt that the text elevated Mary to an uncomfortable level—equal almost to Jesus in that she could heal and, in a way, rose from death after three days. They were shocked by the Dormition’s depictions of Jewish antagonists, who sought to burn Mary’s body but were instead consumed by fire.

The third text of the lecture was the History of Joseph the Carpenter. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the text commonly appeared in apocrypha collections and editors speculated that it had a Greek origin (it is extant only in Coptic and Arabic). Recently, Alin Suciu has placed it among the fifth-century Pseudo-apostolic memoirs, all of which seem to have been composed in Coptic in fifth-century Egypt. The students were struck by its emotional verisimilitude; whereas Mary of the Dormition welcomes death and receives great honours on her deathbed, here Jesus weeps for his dying adoptive father and Joseph fears the approach of the angel of death. In previous years I have shown the class a short clip of the death scene of Joseph from the 1998 Jesus television miniseries starring Jeremy Sisto (one of my favorite Jesus films because of its use and invention of apocryphal traditions). The scene captures the same affectiveness that we see in Hist. Jos. Carp., though it is rather banal in comparison to the apocryphal account (no angel of death here). To bring in more about the angel of death, I spent a few minutes discussing the Investiture of Abbaton, another Coptic text from the same genre of literature. It tells the story of how the angel Muriel becomes the Angel of Death.

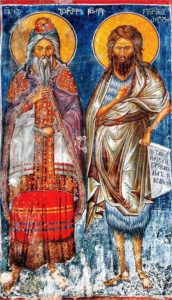

The final portion of the lecture was spent on John the Baptist traditions. I began with a look at the flight to the wilderness and the death of Zechariah from the Infancy Gospel of James—just to remind the students about what this text says about John because the other Baptist apocrypha typically incorporate these stories into their texts. I then turned to our assigned text, the Life of John the Baptist by Serapion, which contains the remarkable story of John’s flying head. I noted in particular how the text weaves together canonical and noncanonical traditions without any concern for the boundary between them. The same phenomenon occurs in the various apocryphal accounts of the martyrdom of John that I am working on for the second volume of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. One of these, actually titled the Martyrdom of Zechariah, has never been published before. I presented the students with a short excerpt from it to give them a sense of some of the elaborations found in these martyrdoms. In this scene, the young John is taken to the temple where Zechariah’s body is hidden so that John and his father can be baptized by Jesus:

5 1When John had been in the desert for four months, the Lord went from Egypt with the archangel to Bethlehem into the temple of God. And he commanded Uriel and brought John there during the night. And the four angels—Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael, in whom also God is present—came out and they brought the body of Zechariah.

2The Lord blew on him and he gave breath of life to him. And rising, everyone turned toward the service.

3And the Savior commanded and water came out from the spring of immortality in the holy of holies in the temple. There he baptized first John and forthwith in this way he baptized his father Zechariah.

4The angels shouted “Amen!” And again the angels shouted, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord who is seated on the throne of his glory!” Because this decree and the heavenly water are from the father of men. And again they said, “Amen!”

5Then, the Lord commanded his angels and they took charge of the body of Zechariah and buried him in the temple of God below the altar.

The lecture concluded with a look at the legend of the deaths of the Herods, which is widely attested in Christian literature, not only in the Baptist apocrypha, but also in the Epistle of Herod to Pilate, Solomon of Basra’s the Book of the Bee, and several patristic writers. According to the story (with variations in each text), Herodias’ daughter was playing on ice and fell up to her neck; as her mother attempted to save her, she inadvertently pulled off her head. Herodias herself became blind in one eye. Herod died while sitting with the girl’s head in his lap and lamenting her untimely death; but he did not rest easy, because the earth spit up his body and it was eaten by the birds of heaven. Of course, that’s not how they really died; according to Josephus, Herod Antipas and Herodias died in exile near Lyons after Herod’s removal from power in 39 CE (Ant.252–255; BJ 2.183). Herodias’ daughter Salome went on to marry Philip, and later Aristobulus with whom she had three sons (Ant. 18.137). But Christian writers were unsatisfied with the rather peaceful ends of these nefarious figures, so they created stories in which they died in ways that are more fitting for their crimes.

For more on the texts discussed in the lecture, consult e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha, which features summaries and bibliographies of (almost) all of those surveyed here. Next week we conclude the 2018 New Testament Apocrypha course with a look at anti-Christian gospels and modern apocrypha.

Thanks for sharing. Sounds like a fascinating class. I didn’t know about Herodias pulling off her daughter’s head!

I think you’re absolutely right about Mary traditions. I have an article forthcoming on how quickly Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene were synthesized in early Christian works, and on the scholarly reluctance to acknowledge this.