2018 New Testament Apocrypha Course: Reflections on Week 5

The second of our classes focusing on the ministry of Jesus (that is, the time between his childhood and his Passion) included two letters, two fragmentary texts, and two complete gospels.

We began by reading the Epistle of Lentulus, a letter attributed to a Roman official at the time of Jesus and which contains a detailed description of Jesus. I asked the students to consider as we read evidence from the text that indicates it is a medieval (not ancient) composition—e.g., Lentulus’s use of Jewish terminology he is unlikely to have known (“prophet,” “Nazarene,” the quotation from Psalm 45:2), and the Aryan (rather than Palestinian) looking Jesus he describes. I noted that many scholars of Christian Apocrypha would label this text “inauthentic” or a “forgery” and asked the class to consider why a later apocryphal text should be valued differently from ancient apocrypha. To my mind (and to the minds of several of the students who responded), there really is no difference—they are all fictional representations of figures from early Christianity and all worthy of study for what they can tell us about the interests of the writer and his/her time period.

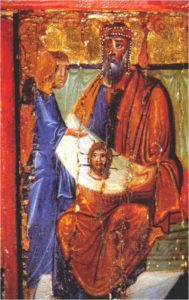

We turned next to the Abgar Correspondence and a discussion of H.J.W. Drijvers’ theory that the letters were created to obscure the history of Manichean evangelization in Edessa (e.g., Mani’s apostle Addai preached in Syria, the Correspondence and its sequel the Doctrine of Addai replaces Mani’s disciple with a Christian missionary of the same name). We watched also an excerpt from the video Letters of Faith, a short (35 min.) docu-drama about the Abgar Correspondence. The film was released in 2007 by the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. It is quite melodramatic at times and plays fast and loose with the source material (Eusebius and the Doctrine of Addai) but it is fun to watch and a rare treat—a devotional film about an apocryphal text!

I began my discussion of the Gospel of the Savior by stating that everything I say about the text in my Secret Scriptures Revealed book I no longer believe (sometimes things move fast in scholarship). This is due to becoming acquainted with Alin Suciu’s work on the text. The text’s first editors, Charlie Hedrick and Paul Mirecki, believed it was a narrative gospel translated from Greek and originally around the length of the Gospel of Matthew. Suciu places it instead firmly within Coptic Christianity, specifically in a genre of texts called “Pseudo-Apostolic Memoirs”—homilies attributed to famous church leaders with embedded apocryphal texts purported to have been found in Jerusalem. I think this is one of the most exciting area of Christian Apocrypha scholarship, one that I hope will attract more scholars and students in the years ahead. Three of the texts appeared in the first volume of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures and the second volume will feature three more. We moved more quickly through the Gospel of Peter, with a brief overview of two theories of compositions: Raymond Brown’s “secondary orality” (Gos. Pet. joined the various traditions found in the canonical Gospels from the writer’s memory) and John Dominic Crossan’s “Cross Gospel” (Gos. Pet. is a witness, and a better witness at that, to an account of the Passion Narrative that precedes the canonical Gospels). I threw in a brief scene from the documentary Bible Hunters in which intrepid archeologist Jeff Rose pokes around the cemeteries of Akhmim, where the primary manuscript of the Gospel of Peter was found in the late nineteenth century.

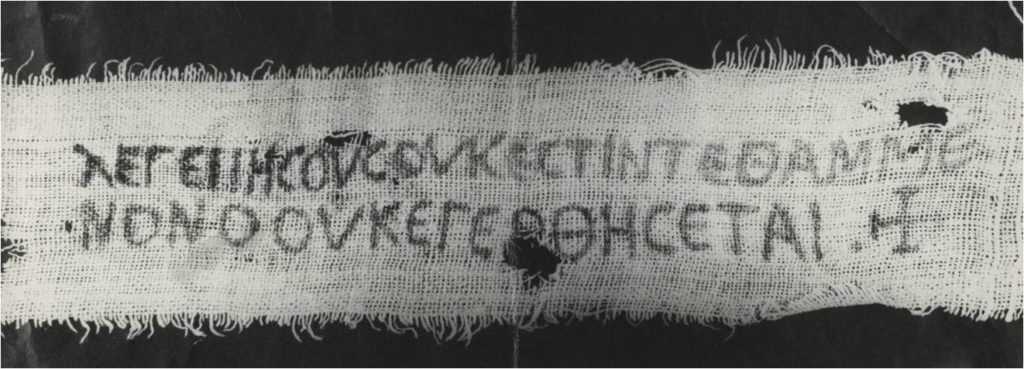

Our examination of the Gospel of Thomas began with an overview of the sources for the text—in Greek and Coptic. I mentioned also a strip from a burial shroud that was once in the possession of Henri-Charles Puech, one of the early scholars of the Nag Hammadi Library. The shroud features Gos. Thom. 5: “Jesus says, ‘There is nothing buried that will not be raised.’” The day before class I had asked members of the SBL Christian Apocrypha Section Facebook page if anyone had a decent image of the shroud. I was directed to the Claremont Colleges Digital Library and found also a paper on the shroud by Anne Marie Luijendijk. Before long, a number of scholars added their voices to the post, raising doubts about the shroud’s authenticity. I had accidentally renewed interest on this artifact and helped to bring awareness to its place in contemporary discussion about forgeries (which helped me to connect our discussion of Gos. Thom. to the Epistle of Lentulus). Not bad for a day’s work.

Our examination of the Gospel of Thomas began with an overview of the sources for the text—in Greek and Coptic. I mentioned also a strip from a burial shroud that was once in the possession of Henri-Charles Puech, one of the early scholars of the Nag Hammadi Library. The shroud features Gos. Thom. 5: “Jesus says, ‘There is nothing buried that will not be raised.’” The day before class I had asked members of the SBL Christian Apocrypha Section Facebook page if anyone had a decent image of the shroud. I was directed to the Claremont Colleges Digital Library and found also a paper on the shroud by Anne Marie Luijendijk. Before long, a number of scholars added their voices to the post, raising doubts about the shroud’s authenticity. I had accidentally renewed interest on this artifact and helped to bring awareness to its place in contemporary discussion about forgeries (which helped me to connect our discussion of Gos. Thom. to the Epistle of Lentulus). Not bad for a day’s work.

After an open discussion about how Jesus is portrayed in Gos. Thom., I turned to an overview of the various theories of origin for the text, from those who see it as early and independent of the New Testament gospels (Crossan, Koester), to those who see it as late and dependent (Goodacre, Perrin), and those who see it as both early and late (Pearson, DeConick). I capped it all off with a few scenes from Stigmata, a 1999 thriller that features Gos. Thom. prominently in its plot.

We finished up with a very quick look at the Gospel of Philip (specifically, 63.32-64.5 on Mary Magdalene as Jesus’ “companion”). This segued into a mention of how this saying figures prominently in Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code as proof that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene. From there I turned to the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, a modern apocryphon inspired by the interest in Jesus’ marital status that came partly as a result of Brown’s novel. Which brought us back around to the Epistle of Lentulus, because like Lentulus, the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife is still a valid object of study as an expression of the Christianity of its (our!) time.

I wanted to mention as part of this final section of the lecture that scholars sometimes are dismissive of a newly-discovered text simply because they object to its content (either it cannot possibly be authentic because Jesus would never DO that! or it appears to reflect contemporary, not ancient, interests). James McGrath (Butler University) pointed out during the criticism that attended the publication of the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife that if a fragment containing the Gospel of Philip 63.32-64.5 was discovered today, likely it would receive the same skeptical reception as the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife. Given the often shocking content of some apocryphal texts, scholars of Christian Apocrypha need to proceed cautiously in their assessments of the evidence.