2017 SBL Diary: Day Three

The third and (for me) final day of the annual meeting began with a breakfast with the NASSCAL executive. The annual meeting presents an opportunity for the executive to meet informally, with a loose gathering of whoever happens to be at SBL—which is usually most of us. I presented the group with an update of our various projects, including the e-Clavis (now at 64 texts completed and another 26 in progress), the Early Christian Apocrypha series (with Brandon Hawk’s Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew translation at the press and Lily Vuong’s Protevangelium of James near completion), the Studies in Christian Apocrypha series (with one title in progress, one in the proposal stage, and another two possibilities discussed), and the first NASSCAL conference (planned for the University of Virginia in September of October 2018). NASSCAL is now two-and-a-half years old and looking back, we have accomplished an awful lot in that short time.

After breakfast Brent Landau and I headed over to the review session for our book New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. It featured an all-star panel: David Brakke (Ohio State University), Philip Jenkins (Baylor University), Valentina Calzolari Bouvier (University of Geneva), Julia Snyder (Universität Regensburg), Judith Hartenstein (Universität Koblenz – Landau), Christoph Markschies (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin – Humboldt University of Berlin), and for a student perspective, J. Gregory Given (Harvard University). Two of the respondents have already posted their comments online (Jenkins and Brakke). All of the reviewers were effusive in their compliments about the volume: Calzolari Bouvier, for example, called it “a beautiful achievement,” Jenkins “an impeccable work of scholarship” and “a wonderful treasure house” that “maintains a ferociously high scholarly standard throughout,” Brakke “a triumph in every way, a precious gift to biblical scholars, historians of Christianity, and any other curious reader,” and Hartenstein “an enormous achievement for many branches of theological studies.” Many of the respondents touched on a few key topics: the limits of the literature (how much “more” is there?), the use of genre categories for the texts, and the definition of Christian apocrypha. Rather than summarize each of the panelists’ comments one-by-onen, I will present here a spruced up version of my response to them.

After breakfast Brent Landau and I headed over to the review session for our book New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. It featured an all-star panel: David Brakke (Ohio State University), Philip Jenkins (Baylor University), Valentina Calzolari Bouvier (University of Geneva), Julia Snyder (Universität Regensburg), Judith Hartenstein (Universität Koblenz – Landau), Christoph Markschies (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin – Humboldt University of Berlin), and for a student perspective, J. Gregory Given (Harvard University). Two of the respondents have already posted their comments online (Jenkins and Brakke). All of the reviewers were effusive in their compliments about the volume: Calzolari Bouvier, for example, called it “a beautiful achievement,” Jenkins “an impeccable work of scholarship” and “a wonderful treasure house” that “maintains a ferociously high scholarly standard throughout,” Brakke “a triumph in every way, a precious gift to biblical scholars, historians of Christianity, and any other curious reader,” and Hartenstein “an enormous achievement for many branches of theological studies.” Many of the respondents touched on a few key topics: the limits of the literature (how much “more” is there?), the use of genre categories for the texts, and the definition of Christian apocrypha. Rather than summarize each of the panelists’ comments one-by-onen, I will present here a spruced up version of my response to them.

The field of Christian apocrypha is a mixture of tradition and innovation. Our earliest scholars published editio principes based on late manuscripts not representative of the original texts and gave them names that are not found in any of the sources. The Protevangelium of James and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas are two good examples of this; more on point, I just published a critical edition of the Syriac Infancy Gospel of Thomas using the traditional name of the text, yet it does not appear in any of the manuscripts, and divided it into the traditional chapters and verses despite the fact that some chapters are not present in the Syriac text (readers may wonder where ch. 10, 17 and 18 are). But we use these titles and conventions because we are stuck with them—we want other scholars to be able to correlate our work with what has come before.

As for innovation, despite the pull of the editio principes, we are always looking for new versions of texts and new texts to publish, encouraged too by the new philology to value every variation of a text as an object of study. And we have been engaged in the last few decades in redefining the scope of our field, moving away from “New Testament Apocrypha” as a service industry for understanding the development of canonical texts and for reconstructing the historical Jesus, to “Christian Apocrypha” as a temporally and generically limitless area of study that encourages us to engage with scholars in a wide range of other fields.

It is both tradition and innovation that is reflected in the More New Testament Apocrypha series. As Valentina points out we opted for a traditional title for the collection because it coheres with other volumes in English that we set out to supplement, yet we often use “Christian Apocrypha” within the book. The title is influenced also by our “sister publication” Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures, which carries some of the same baggage (and “Old Testament” always makes me cringe). So, the lure of tradition—both longstanding and recent—overwhelmed our desire for innovation. And again, “New Testament Apocrypha” has greater brand recognition—we want potential readers to know what they are getting.

The desire to parallel MOTP also influenced the arrangement of the texts within the volume. MOTP groups its texts in two categories: Texts Ordered According to Biblical Chronology, and Thematic Texts. So it largely follows the arrangement of the OT/HB, at least in the sense of a historical movement from creation to hellenism. The convention for arranging Christian apocrypha is similarly influenced by its canonical counterpart, following the genres of gospels, acts, letters, and apocalypses, and a certain order within those categories (e.g., infancy material before passion material). Julia and Greg raise valid concerns about this arrangement. Julia asks “as a field, can we please stop using these categories?” and notes all sorts of problems with category designations (e.g., Ps.-Dionysius is a good example of a text better suited to Acts than Letters); mind you, even canonical texts blur genre boundaries—the Synoptics include an apocalyptic section, Luke-Acts is unnecessarily separated, and many of the letters are better characterized as sermons; of course, that doesn’t make the categories we use alright, but it is not a problem confined to Christian apocrypha.

So, despite our organizational strategy for MNTA, I agree that we should think more about the categories we use and how they affect interpretation; and stay tuned, because volume two will include the Teaching of the Apostles, a church manual, a genre that does not appear in the majority canon, though there are two of these kinds of text in the Ethiopic Bible. Note in this connection Valentina’s comment about the different shape of the Armenian canon and that our conceptions of canon are often restricted by the 27-book collection; this changing and varied view of canon also warrants more discussion.

Philip Jenkins raises the issue of even broader categories, noting the false distinction between OTP and NTA, because some OTP are Christian works and sometimes even include Christian figures within them. This is particularly the case for the Cave of Treasures, which Philip mentions, but the biggest concerns for us in editing the volume were two texts that were to be included in the as-yet-unpublished (at the time) MOTP collection: the Apocryphon of Seth, which is a portion of the Opus imperfectum in Matthaeum that relates to the Revelation of the Magi, and the Tiburtine Sibyl. We ended up including only a summary of Revelation of the Magi in our volume (since Brent’s English translation had recently appeared and was accessible to readers) but not the material from Opus imperfectum, and MOTP translated their version of the Tiburtine Sibyl from Greek whereas ours was from the Latin. The Investiture of Abatton (included in MNTA) equally could fit in MOTP as much of it deals with the roles of angels in the fall of the first humans. Certainly the categories of OTP and NTA are porous but our chief goal was to avoid duplication, and it helps that the two collections are not restrictive in which tradition, Jewish or Christian, authored the texts—they are not Jewish Pseudepigrapha, for example, or Christian Apocrypha, though in some contexts these terms are more useful.

Despite all of these traditional qualities to MNTA, the volume does innovate in some ways. Greg and Julia applaud our wide-open mandate to go beyond the 3rd/4th century, though we could not have done so without having the way paved for us by the expansive French, German, and Italian collections. Greg and Julia appreciate reading earlier, more well-known apocrypha alongside later texts usually categorized as hagiography (e.g., Acts of Cornelius). Such divisions feed an artificial distinction that characterizes apocrypha as early, rejected, heretical; and hagiographa, which was continually created, valued alongside the Bible (particularly as readings for the feast days of the saints), and orthodox. I’m happy to be contributing to the dissolution of this dichotomy.

Philip Jenkins’ recent book The Many Faces of Christ makes a similar argument—that apocrypha continued to be read and even created after the closing of the canon; they weren’t all burned in a pogrom against heretical literature. Philip points out here in his review that our abandonment of the temporal limit of the 3rd/4th century allows us to include modern apocrypha in the series (he asks “Why should 1960 be less valid a topic of study than 960?”). I agree, but with some caveats. He suggests that modern fiction or film about Jesus could also be included—I would object here based on my own definition of apocrypha that limits the field to texts that claim or imply first-century authorship (thus leaving out modern fiction and accounts of visions, such as those experienced by Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich). That said there is a modern apocrypha collection planned for NASSCAL’s series Studies in Christian Apocrypha; it will be assembled by Bradley Rice and I and will focus on what I call “scholarly apocrypha”—texts created by modern writers but said to have been found in one or more ancient manuscripts and in most cases are presented more as an object of study than for spiritual reflection.

Another innovation, this one mentioned by Greg, is the publication of multiple versions of texts. This decision was dictated to some extent by the variety of the materials and is not always followed consistently (we have multiple versions of On the Priesthood of Jesus but not the equally-varied Epistle of Christ from Heaven or the Apocalypse of the Virgin). But certainly the reconstruction of the “original text” is not something we encouraged and we’re glad that readers appreciate seeing both multiple recensions of texts and detailed notes about variant readings.

Greg mentions also that the introductions show some fluidity and applauds particularly those that devote some space to the use and dispersion of the text over time; the suggestion to encourage other contributors to do the same is a good one and as we work on volume two, we will certainly ask our contributors to consider these aspects of the texts.

I finished my response with a quick plea to buy the book (why not? apparently it’s a “beautiful achievement”). Brent then offered his response, focusing on comments made by Hartenstein, Markschies, and Brakke and there was a brief discussion with the audience. The session segued into a business meeting planning the sessions for next year, which will include a joint session with Religious Competition in the Ancient World and perhaps a partnership with the group examining canonical and noncanonical motifs, themes, etc. that I mentioned in my last post.

Following the session, Janet Spittler and I had a business lunch with Trevor Thompson of Eerdmans, the publisher of MNTA and my Secret Scriptures Revealed book. The three of us discussed a possible project that can serve as a companion to the MNTA series.

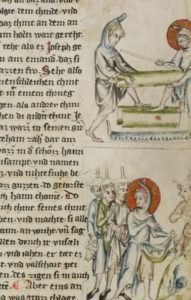

The only afternoon session I attended was Bible and Visual Art which featured a paper by Geert Van Oyen (Université catholique de Louvain) on “The Pictorial Representation of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Klosterneuburger Evangelienwerk (ca. 1340).” The manuscript (Schaffhausen, Stadtbibliothek, Generalia 8) features 21 images accompanying nine stories in Middle-German from Jesus’ childhood, culled (more likely) from the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew. Other stories in the sprawling work come from canonical texts, isolated stories, and apocryphal texts such as the Gospel of Nicodemus. There are more medieval manuscripts out there with such images, though few have been brought into Christian apocrypha scholarship; Van Oyen’s paper is a welcome push toward seeking out more.

The day concluded with a trip downtown with some Canadian friends for a nice dinner away from the conference center. Most of us there (Alicia Batten, Colleen Shantz, Bob Derrenbacker, Dan Smith, and I) met back in the late 90s in John Kloppenborg’s Synoptic Problem class at St. Michael’s College (on the University of Toronto campus). It’s impressive how many of us from that class have remained in academia and have gone on to some success. Kloppenborg must have been working some kinda magic.

And so concludes my reminiscences of the 2017 SBL Annual Meeting. See you next year in Denver.