2017 SBL Diary: Day One

Every year after the SBL Annual Meeting I take some time to compile a summary of my activities—the sessions I attended and/or participated in, meetings I had with scholars and publishers, books I purchased, and receptions I crashed. I do this for those interested in Christian Apocrypha who could not attend the meeting and also in lieu of tweets because Wi-fi access tends to be somewhat spotty. Since I write at a snail’s pace, this summary will be split into three separate posts that will appear over the next few days.

I flew into town Friday around 2:30 pm—far earlier than normal—and thought I could spend the rest of the afternoon leisurely wandering around the book display. That way I wouldn’t have to squeeze the tour in between papers or skip a session. Unfortunately, the display was not yet open, so I had to find something else to do (and who am I kidding? it’s not like I would only go once anyway). So I went back to my room to iron my balled-up suit and do a little work before meeting up with Brent Landau. Over dinner we discussed, among other things, the progress on the second volume of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures, which has been a bit sluggish due to some contributors having to withdraw because of other commitments or changes in their careers. The first volume contains a provisional list of texts to be included in vol. 2, and that list is looking less and less accurate as each day passes. But everything will be okay in the end, even if the book has to be delayed by about a year (and the second volume of our sister publication, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures, has not appeared yet, so I think we’re doing okay). After dinner I went back to my room and waited for the arrival of my “conference wife” Zeba Crook (Carleton University).

The true first day of the conference began with our first Christian Apocrypha session, which bore the title “Apocryphal Letters, Legends, and Sayings.” The first paper was by Kimberly Bauser, a graduate student at Boston College: “Put on Your James Face: Pseudonymous Prosopopoeia and Epistolary Fiction in the Apocryphon of James.” Bauser described the text as a “literary nesting doll” with an epistolary framework by James around a post-resurrection dialogue between Jesus and the apostles. Bauser asked, did the author intend to be believed or was writing in James’ name simply a rhetorical exercise? She concluded that the epistolary frame was created for those on the fringes of the community who would be attracted by the James attribution and thus give the revelation dialogue a fair hearing. To illustrate, Bauser used the analogy of students who come into a Christian literature class interested in the gospels but then learn that the content of the texts is more important than the names they bear.

The second paper was delivered by Phillip Fackler, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. In “Survival of the Most Banal: Paul’s Letter to the Laodiceans and the Correspondence with Seneca,” he commented how scholars find the two texts banal because they don’t offer much that is different about Paul from what we read in the New Testament: Laodiceans is mostly cobbled together from Philippians and seems to have been composed simply to fill the gap left by Paul’s mention of a letter to the Laodiceans in Colossians 4:16, and the Seneca correspondence is little more than an exchange of praise between the two writers. Nevertheless, the two texts were extremely popular among orthodox Christians—Ep. Lao. appears in a number of Vulgate codices and there are over 400 manuscripts that contain Ep. Paul Sen.—because they meet the expectations of readers who are more likely to preserve a text that looks familiar than one that has radically different teachings or concepts. Fackler noted also that both texts invoke Paul as an ethical teacher, though it seems to me that the writers are more interested in Paul as a martyr and letter writer—the actual contents of Paul’s letters seem to matter little to the apocryphal writers. Recent papers by Jason BeDuhn and Gregory Fewster have argued that the early church seemed to have little interest in Paul’s ethics, and that seems borne out in these two apocryphal texts. In the subsequent discussion Fackler made an interesting point that a reader of a collection of Paul’s letters that included Ep. Lao. may have seen Philippians as an expansion of Ep. Lao., rather than Ep. Lao. as a “banal” reduction.

Another student, David P. Griffin from the University of Virginia, came next with “Psalm-Quotations in the Epistle of the Apostles and the State of Christian Psalmody in the Second Century.” Ep. Apos. features a number of quotations introduced with the phrase “as it is written” or “as written in the prophet.” Several of these are agrapha—statements by or about Jesus not actually found in other texts, or at least not texts that have survived—and others come from the Psalms. Frequently, Griffin said, the Psalms quotations betray a lack of deep knowledge of Jewish scripture and suggest that they were known to the author from liturgical materials. If so, Christians may have sung or recited psalms earlier than what is commonly believed, perhaps at agape meals, which are featured prominently in ch. 15 of the text. Bart Ehrman was present at the session and asked Griffin about the agrapha, noting that modern Christians frequently quote something from Scripture that does not actually appear in the Bible—consider, for example, a poll that showed that 80% of practicing evangelicals believed the saying “God helps those who helps themselves” is biblical.

The fifth paper was “East of the Magi: An Old Uyghur (Turkic) Text on their Visit to the Young Jesus” by Adam McCollum of the University of Notre Dame. The paper is a preview of a text McCollum is working on for MNTA 2. It is found in a tenth-century manuscript discovered over a century ago but now lost; fortunately it is accessible through photographs published in the 1907/1908 editio princeps by F. W. K. Müller. The Old Uyghur materials were found in Central Asia in the nineteenth century; about 75% of the texts are Buddhist and the Christian texts include a copy of the Acts of Paul and Thecla. The Magi text is about four pages long but the beginning is missing. It includes a story of the Magi and another of Herod’s murder of Zechariah, the latter presumably taken from the Protevangelium of James or a related text. In the Magi tale, the travelers from the east bring three gifts to Jesus representing the three roles of god, king, and healer; they expect Jesus to take one and thus reveal his destiny, but he takes all three.

The final paper of the session was delivered, once again, by a graduate student: Jeremiah Bailey of Baylor University. In “Male Angels, Resurrection Marriage, and Manly Mary: A Possible Connection Between GTh 114 and the Synoptics” Bailey looked for an explanation of the puzzling logion in the Question about the Resurrection from Mark 12:18–27 (and par.) where Jesus answers the question of whose wife will the woman who married seven brothers be in the resurrection. Jesus answered, “when they rise from the dead, they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven.” Bailey noted references in other literature (such as 1 Enoch) indicating that angels are all male. Jesus’ response to Peter in Gos. Thom. 114 (“I will lead her that I may make her male, in order that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who makes herself male will enter into the kingdom of heaven”) becomes more intelligible if it is subjected to an “angelomorphic reading,” and may help also with understanding log. 22 (“when you make the male and the female one and the same, so that the male not be male nor the female female”). Bailey himself is surprised that his approach is not reflected in the scholarly work on the text and several audience members praised his argument.

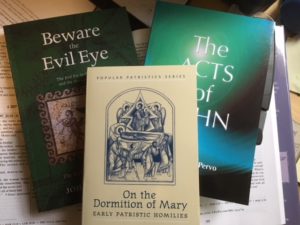

After the session, Bradley Rice (McGill University) and I caught up over lunch, which ended a bit too late for me to catch any of the early afternoon sessions—reason enough to head to the book display! Among my purchases are vols. 2–4 of John H. Elliott’s Beware the Evil Eye: The Evil Eye in the Bible and the Ancient World from Wipf & Stock (will I be lost without having read vol. 1?), the latest volume in the Polebridge Early Christian Apocrypha series (The Acts of John by Richard Pervo), and a collection of early patristic homilies on the Dormition of Mary from St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

After the session, Bradley Rice (McGill University) and I caught up over lunch, which ended a bit too late for me to catch any of the early afternoon sessions—reason enough to head to the book display! Among my purchases are vols. 2–4 of John H. Elliott’s Beware the Evil Eye: The Evil Eye in the Bible and the Ancient World from Wipf & Stock (will I be lost without having read vol. 1?), the latest volume in the Polebridge Early Christian Apocrypha series (The Acts of John by Richard Pervo), and a collection of early patristic homilies on the Dormition of Mary from St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

From the book display I made my way to the Nag Hammadi and Gnosticism session. The highlight of the session was the highly-anticipated paper by Geoffrey Smith and Brent Landau (both of the University of Texas at Austin) entitled “Nag Hammadi at Oxyrhynchus: Introducing a New Discovery.” I knew ahead of time what text the two were going to debut but I had promised to keep that information to myself. Smith began the discussion with a list of all of the texts from Nag Hammadi that are available in Greek—Gospel of Thomas, Wisdom of Jesus Christ, and (not from Nag Hammadi but often associated with it in scholarship) the Gospel of Mary—before revealing the new text: 1 Apocalypse of James. This was greeted with a bit of a gasp in the room, and it is certainly exciting to have the text in Greek, or at least a portion of it. The manuscript, which has been sitting in a cabinet at Oxford for a century, is dated to around the fifth or sixth century. It follows closely the text as found in Codex Tchacos, so it does not provide any new or radically different readings. Landau took over the second portion of the presentation to discuss the scribe’s use of mid-dots to divide syllables—a practice found only in manuscripts used to teach reading. Landau remarked that it is odd that of all the texts that a teacher could chose from (such as the Iliad or the Psalms), she or he chose this “obscure Christian writing.”

My conference obligations done for the day, I met up with Andrew Gregory, co-editor of the Oxford Early Christian Gospel Texts series and the Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Apocrypha. I’ve corresponded with Andrew for years but we have not met until now and we chatted about our various projects over dinner. The night finished with taking in some receptions with my Canadian friends—first the Wabash Center (where the booze flows freely) and then the Toronto School of Theology (where it trickles slowly, though by that time the two free drinks were just enough). At the TST reception I ran into Gregory Fewster (University of Toronto) and we discovered that we had both done some detective work on a peculiar apocrypha-related manuscript at the University of Toronto. We decided to join forces and work on the manuscript together. Look for that sometime in the future.