Christian Apocrypha and Pilgrimage, Part 3

In the first post in this series I discussed the visits of pilgrims to locations mentioned only in apocryphal texts, in the second I provided an overview of the texts that expand on the Flight to Egypt to create a fictional pilgrimage map for those who want to follow in the Holy Family’s footsteps, now I turn to some aspects of the intersection of apocrypha pilgrimage that remain largely unexplored by scholars.

The first of these is the connection between the production of apocryphal texts and the pilgrimage locations associated with them. Egeria mentions reading copies of the works of Thomas at the apostle’s tomb in Edessa (Itin. Eger. 19.2) and while in the city she received a copy of the Abgar Correspondence (Itin. Eger. 19.19). When visiting the martyrium of Thecla in Isaurian Seleucia, Egeria read tales of the saint (Itin. Eger. 23.5), likely from the Life and Miracles of Thecla—a retelling of Thecla’s story from the Acts of Paul along with an account of the end of her life in Seleucia followed by a series of posthumous miracles performed on behalf of pilgrims at the site. The account of Thecla’s final days in Seleucia includes a trip to and from Daphne, which functioned as an itinerary for fifth-century pilgrims on their way to Thecla’s sanctuary.

Several late antique apocryphal acts also establish a connection between characters in the narratives and particular shrines. The Acts of Barnabas, for example, documents the travels of Barnabas through Seleucia, Cyprus, Perga, Antioch, Cilicia, and cities in between before concluding at Cyprus, where Barnabas is martyred. The cities in Cyprus are not chosen by accident: they are all associated with fifth-century church districts and pagan temples. The text also provides readers with the date of Barnabas’s death (11 June), which is here established as the feast day of the saint. A contemporary text, the Encomium of Barnabas, retells the Acts and finishes with Barnabas appearing to Anthemis, the bishop of Salamis in 488 and revealing to him the location of his remains.

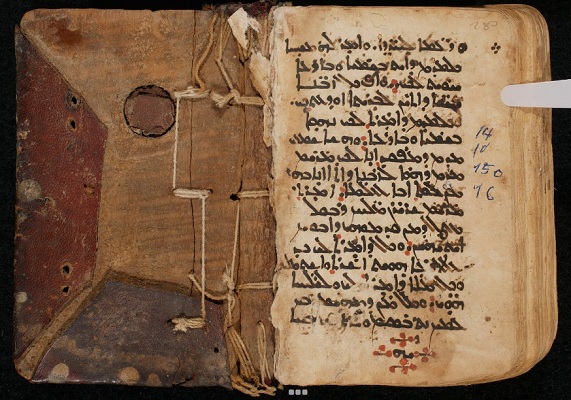

A similar structure is observable in the Acts of Cornelius. Cornelius is assigned the city of Skepsis to evangelize. After some exploits there, he dies and his burial place becomes lost to memory. In the fifth century, the location of Cornelius’s body is revealed in a dream to Silvanus, the bishop of Troas, and he is instructed to build Cornelius a sanctuary and place the coffin within it. Later a painter named Encratius is commissioned to decorate the shrine with an image of the saint; he is able to capture his image because Cornelius appears to him and reveals his features. Both of these texts establish a particular location for the celebration of the saint and provide back stories for how the site was selected and for how the saint’s remains were discovered and interned there. These locations are likely the place of origins for the texts and would be suitable also as sites for the creation and dissemination of copies that could be purchased by pilgrims who visited the sites and wished to return home with a souvenir of their experience. Even today one can purchase transcriptions and translations of such texts produced for visitors of monasteries and churches. Consider, too, such examples as the West Syriac Life of Mary codices that collect apocryphal Marian texts, sometimes grouped with various memre on the Virgin, and the East Syriac History of the Virgin manuscripts, many of which derive from the monastery of Notre-Dame des Semences in Alqoš. The compilation and centralized dissemination of these codices suggests production as souvenirs for pilgrims or devotees of sites dedicated to the worship of Mary.

Codices also associated also with Thecla devotion in Egypt. The Life of Eugenia, composed in the late fifth century, tells of how the saint travelled out from Alexandria to a nearby village and along the way read a miniature codex of Thecla’s adventures. Two such miniatures of Thecla exist today: P. Oxy. I 6 (5th cent.) and P. Ant. I 13 (4th cent.). It is tempting to associate other ancient apocryphal miniatures with pilgrimage (e.g., P. Oxy. VI 849 of the Acts of Peter; and P. Oxy. V 840 of an unidentified gospel text).

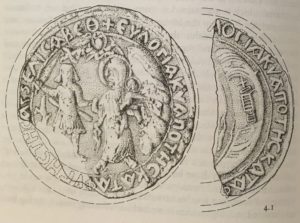

Other pilgrimage souvenirs reveal connections between sacred sites and apocryphal texts. Pilgrims often returned home with ampullae (flasks) containing healing oil or water from the site. Many of these ampullae are decorated with images. The most popular images were of the cross and Jesus’ tomb, but a good portion of them have images associated with the life of Mary. Those that feature the Annunciation often depict Mary spinning and looking back at Gabriel, features found in the Protevangelium of James and related texts. A large number of ampullae from the cult centre of Saint Menas in Mareotis (Egypt) depicts Menas on one side and Thecla on the other, with images derived from her exploits told in the Acts of Paul. One ampulla from the Shrine of St. John in Ephesus includes a seated figure, which some say is Prochorus, the secretary of John and putative author of a fifth-century Acts of John. Another common souvenir containing images is the eulogia (blessing) token. Notable among these are the sixth/seventh-century ceramic medallions depicting the flight of Elizabeth and John, one of which is said to come from Ain Karim, the traditional location of the mountain of refuge as told in Protevangelium of James and several other Baptist apocrypha.

There is much still to be learned from these examples about the interplay of apocrypha and pilgrimage. The itineraries demonstrate that as early as the late fourth century Christians were creating and maintaining associations between sacred places and traditions that appear outside of Scripture, even reading apocryphal texts at these locations that relate to the saint celebrated there. The influence of apocrypha extends to pilgrimage souvenirs—ampullae, eulogia tokens, miniature codices—that contributed to the dispersion of apocryphal texts and traditions to the lands pilgrims called home. The connections between pilgrimage sites and the origins and dispersion of apocryphal texts needs further exploration, not only for what can be learned about literary networks but also for how the destruction or inaccessibility of pilgrimage sites could have contributed to the loss of certain texts. And other texts should be brought into the discussion of apocrypha and pilgrimage, particularly the apocryphal acts with their stories of the travels and martyrdoms of individual apostles—do they too represent a stop on a literary journey on its way toward a full-blown pilgrimage map culminating in celebration of the apostle’s death at a sanctuary stocked with souvenirs? Egeria’s mention of reading the exploits of Thomas in Edessa suggests so, as does the veneration of Thecla in Mareotis. Certainly, pilgrimages to the churches dedicated to the saints included all of these features; what remains unknown is whether the early Christians tried to mimic the apostles’ missionary routes or whether, if the apocryphal acts had survived their pruning by orthodox revisers into little more than martyrdom accounts, they would have developed into the kind of detailed pilgrimage map observable in the Vision of Theophilus tradition.

Scholars of Christian apocrypha, and other fields, are increasingly integrating examinations of material culture (including iconography and the physical features of manuscripts) into their work. Physical evidence associated with pilgrimage, and even the act of pilgrimage itself, intersects with this new direction and offers several opportunities for scholars to explore.