Addenda to the Syriac Tradition of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas: A Neglected Edition of the Life of Mary and a Forgotten Palimpsest

In the short time between when I submitted the manuscript of my new book, The Syriac Tradition of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, to its publisher and when it was printed, two additional sources for the text came to my attention. This was to be expected, particularly for the rather robust Sw recension, in which Inf. Gos. Thom. appears as the fourth of six books in a sprawling Life of Mary collection. It was a big surprise, however, to discover a fifth/sixth-century manuscript belonging to the Sa recension (the best witness to the early form of the text), and that this manuscript had been mentioned in scholarship over a century ago! I promised in the preface to the book that I would publish updates (chiefly via the e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha entries for the three recensions), but I didn’t think I would be doing it so soon!

I will cover the Sw manuscript first. It is an uncatalogued and unnumbered manuscript belonging to the Monastery of St. Ephrem in Holland. It was published in a devotional edition prepared by Julius Y. Çiçek (Die heilige Meryem/Tad’itho d’yoldath aloho Maryam. Holland: Bar Hebraeus Verlag, 2001) that came to my attention via Grigory Kessel. These kind of editions are fairly common in places like Cairo and the monasteries of Greece and essentially entail a transcription of a single manuscript, sometimes with translation. Çiçek’s edition is significant not only for its use of a previously unknown manuscript but also because it is the first ever publication of the entire West Syriac Life of Mary compendium, which includes the Protevangelium of James, the Vision of Theophilus, Inf. Gos. Thom., and the Six-Books Dormition of the Virgin. My volume includes an edition and translation of only the Inf. Gos. Thom. portion of the collection. The edition draws from 19 manuscripts, and I discuss another six that lack Inf. Gos. Thom., and note 14 extant in Garšuni; Charles Naffah is working on a proper scholarly edition of the full corpus.

I will cover the Sw manuscript first. It is an uncatalogued and unnumbered manuscript belonging to the Monastery of St. Ephrem in Holland. It was published in a devotional edition prepared by Julius Y. Çiçek (Die heilige Meryem/Tad’itho d’yoldath aloho Maryam. Holland: Bar Hebraeus Verlag, 2001) that came to my attention via Grigory Kessel. These kind of editions are fairly common in places like Cairo and the monasteries of Greece and essentially entail a transcription of a single manuscript, sometimes with translation. Çiçek’s edition is significant not only for its use of a previously unknown manuscript but also because it is the first ever publication of the entire West Syriac Life of Mary compendium, which includes the Protevangelium of James, the Vision of Theophilus, Inf. Gos. Thom., and the Six-Books Dormition of the Virgin. My volume includes an edition and translation of only the Inf. Gos. Thom. portion of the collection. The edition draws from 19 manuscripts, and I discuss another six that lack Inf. Gos. Thom., and note 14 extant in Garšuni; Charles Naffah is working on a proper scholarly edition of the full corpus.

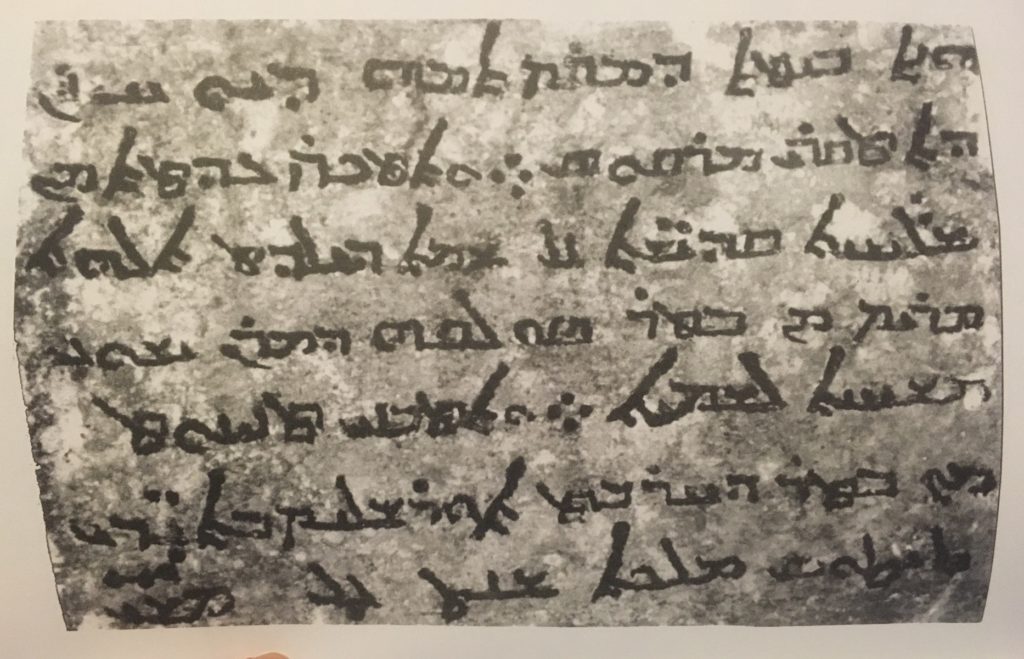

Çiçek’s edition is slightly different from other devotional publications in that it relies on two manuscripts: the one on hand at the monastery and another from the Mingana collection (Syr. 560; assigned the siglum C in my edition and dated 1491). The Holland manuscript is dated 1567 and was produced in Gargar, near the Turkish city of Adiyaman. It is complete, which is helpful given that many of the Life of Mary manuscripts lack at least portions of book one. An untitled image presumably of the manuscript appears in the edition; surprisingly, the script is East Syriac, rather than the western Serto that one would expect.

As interesting as Çiçek’s edition is, the Sa manuscript is a much more exciting find, though takes a little more time to explain. The story begins with the publication of a famous palimpsest manuscript found at Sinai (St. Catherine’s Monastery, syr. 30) in 1892 by Agnes Smith Lewis and her sister Margaret Gibson. It is an eighth-century collection of lives of female saints written over pages taken from multiple codices, including a fifth/sixth-century copy of the Old Syriac Gospels (the first fourteen quires, comprising 142 leaves), the Acts of Thomas (quires 15, 16, and 17), four leaves of the Gospel of John in Greek from the fourth century (quire 15), and part of 6 Bks. Dorm. (quire 16). The gospels were published as Robert L. Bensly, J. Rendell Harris, and F. Crawford Burkitt, with an introduction by Agnes Smith Lewis, The Four Gospels in Syriac Transcribed from the Sinaitic Palimpsest (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1894). The overwriting was published as Agnes Smith Lewis, Select Narratives of Holy Women from the Syro-Antiochene or Sinai Palimpsest as Written above the Old Syriac Gospels by John the Stylite, of Beth-Mari-Qanûn in A.D. 778 (Studia Sinaitica 9–10; London: C.J. Clay and Sons, 1900), with the Acts of Thomas (text, translation, and notes) in an appendix by Burkitt (pp. 23–44) and the Greek Gospel of John in another (pp. 45–46).

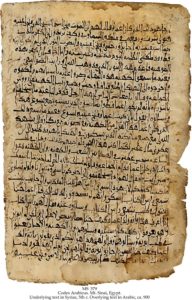

At the time, Smith Lewis believed that another Sinai manuscript (St. Catherine’s Monastery, ar. 588) used additional leaves from the same palimpsest (Four Gospels, p. xvii), based in part on “the coincidence of the contents.” The manuscript is comprised of 69 folios; the overwriting is a ninth/tenth-century Prophetologion (Old Testament lectionary used in the Byzantine tradition), and the underwriting is from two Syriac manuscripts and a few fragments in early Arabic and Christian Palestinian Aramaic. The Syriac portions are significant parts of 6 Bks. Dorm. (excerpt given in Four Gospels, p. xvii), Prot. Jas., and Inf. Gos. Thom. (excerpt with explicit of Prot. Jas. and beginning of Inf. Gos. Thom. in Four Gospels, pp. xviii–xix). In 1902, Smith Lewis returned to the topic of this palimpsest in her introduction to Apocrypha Syriaca. The Protevangelium Jacobi and Transitus Mariae with Texts from the Septuagint, the Corân, the Peshitta, and from a Syriac Hymn in a Syro-Arabic Palimpsest of the fifth and other centuries (Studia Sinaitica 11; London: C. J. Clay, 1902). She mentions here ar. 588 and ar. 514 as witnesses to Prot. Jas. and 6 Bks. Dorm., though they differ so negligibly from the manuscript published in Apocrypha Syriaca—yet another Sinai palimpsest, later catalogued as Cambridge University Library, Or. 1287—that she did not include readings from them in her edition. No mention is made of ar. 588 also including Inf. Gos. Thom. (and why it escaped not only my attention but also the attention of every other Inf. Gos. Thom. scholar of the last 100 years!). Most importantly she states that she was wrong about ar. 588’s relationship to syr. 30: the two do not re-use the same manuscript after all, since portions of their Dorm. Vir. materials overlap in content (Apocrypha Syriaca, p. v).

As for Sinai ar. 514, it is a ninth/tenth-century Arabic collection of patristic works translated from Syriac. It comprises 175 folios culled from more than ten different Syriac manuscripts containing a range of materials, including Old Testament texts, a herbal treatise, and a sixth-century copy of, once again, Prot. Jas. and Dorm. Vir. Four folios of this manuscript now reside in the Schøyen collection (as MS 579; detailed description at the Schøyen Collection web site); they were published by Stephen Shoemaker as “New Syriac Dormition Fragments from Palimpsests in the Schøyen Collection and British Library,” Le Muséon 124.3-4 (2011): 259–78. The 6 Bks. Dorm. portions of two of the palimpsests have re-examined recently in Sebastian. P. Brock and Grigory Kessel, “The ‘Departure of Mary’ in Two Palimpsests at the Monastery of St. Catherine (Sinai Syr. 30 and Sinai Arabic 514),” Khristiansky Vostok 8 (2017): 115–52.

There are plans now to digitize the Sinai palimpsests and make them freely available on the web site of the Sinai Palimpsests Project. Kessel, who is working for the project, presented some preliminary findings on ar. 514 and ar. 588 at this summer’s Réunion de l’AELAC. His handout, circulated to AELAC members, reveals that the Inf. Gos. Thom. material in ar. 588 is comprised of the following:

fol. 67r–67v=IGT 1–6

fol. 62r–62v=IGT 6–7

fol. 52v=IGT 7–13

fol. 52r=IGT 13–16

fol. 66r–66v=no exact correspondences

For this list, Kessel compared ar. 588 to Wright’s edition of British Library Add. 14484, which lacks portions of chs. 6, 7 and 15; it is possible that fol. 66 contains some of this material, or that it corresponds to the final chapter (19 in the traditional numbering), which is the only portion of the British Library manuscript not included in Kessel’s list.

Until the Sinai Palimpsests Project posts their images, the only knowledge we have of the text of Inf. Gos. Thom. from ar. 588 is Smith Lewis’s excerpt, which agrees sometimes with Wright’s manuscript and sometimes with the other fifth/sixth-century manuscript of the text: Göttingen Syr. 10 (originally from Sinai, and indeed a few additional pages from the manuscript were found among the “new finds” discovered in 1975). I am excited at the prospect of seeing the full manuscript and hope that the images will be posted soon. The palimpsests are also very important for work on the other two texts in these “Life of Mary” collections; together they amount to five witnesses to this combination of texts, and all but one of them derive from the same location (the exception is British Library Add. 14484, which has been traced to tenth-century Baghdad, though it certainly could have been produced at St. Catherine’s). It’s amazing that ar. 588 so completely escaped scholars’ attention, due simply because the only mention of Inf. Gos. Thom.’s presence in it was made in a completely unrelated book. Were it not for Kessel and the Palimpsests Project it would have remained forgotten.