2017 ISBL Preview: “‘Arabic’ Infancy Gospel No More”

I am about to depart for the 2017 International Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Berlin. Slavomír Céplö and I will be presenting at the first of four Christian Apocrypha sessions; for a full listing of the Christian Apocrypha papers at this year’s ISBL see this post. The paper, entitled “‘Arabic’ Infancy Gospel No More: The Challenges of Reconstructing the Original Gospel of the Infancy,” has two aims: to present the current status of our work on the Arabic Infancy Gospel (aka Gospel of the Infancy), and to interact with the session’s theme of “Is this a ‘text’?” (questioning practices of how we title texts and if these titles capture the dynamic, fluid natures of verbal communication). Here is the abstract for the paper:

The Arabic Infancy Gospel (Arab. Gos. Inf.) was first published by Henry Sike in 1697, long before many of the apocryphal texts that now dominate the study of Christian Apocrypha. Only one other edition of the text has appeared in the intervening centuries: from a much-different and likely-superior manuscript at the Biblioteca Laurenziana. Additional manuscripts exist but no one, as yet, has evaluated these witnesses. Nor has there been much effort to integrate into the study of this text the East Syriac History of the Virgin, which shares a large portion of material with Arab. Gos. Inf. This paper presents the results of careful analysis of the manuscript sources for both texts and offers some preliminary observations about how best to present the evidence in a new critical edition. As with many other apocryphal texts, scholars are burdened with and restricted by Arab. Gos. Inf.’s editio princeps, which bestowed upon the text an inadequate title that marginalizes the text in Christian Apocrypha scholarship as a product of a community far beyond the traditional centres of Christianity in the Latin West and the Greek East (though this core is increasingly broadening to include Syriac and Coptic Christianity). The influence of the editio princeps is felt also in determinations of the earliest recoverable form of the text, for the parallel material in the Syriac History of the Virgin certainly preceded the Arabic version, but the Arabic perhaps reflects better the original extent of the text. What must be avoided, however, is the reconstruction of a “Syriac Infancy Gospel” that no longer exists, nor may have ever existed.

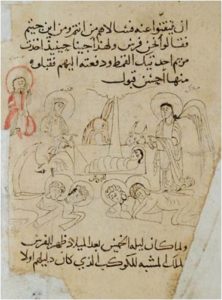

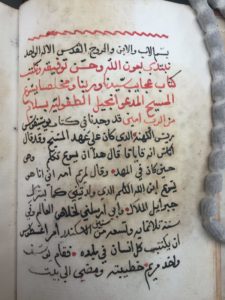

Work on the Syriac sources for the text was completed as part of my newly-released book The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition, which contains a comprehensive overview of the East Syriac History of the Virgin manuscripts, both those that contain Infancy Thomas and those that do not. The Arabic sources were more of a challenge. To date only two manuscripts of the text—named Gospel of the Infancy in their incipits and explicits—have been published: one by Heinrich Sike way back in 1697 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodl. Or. 350) and one by Mario Provera in 1973 (Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, codex orientalis 387). Georg Graf listed about 13 more in the first volume of his Geschichte der christlichen Arabischen Literatur (1944). No-one, it seems, has returned to this list to see what the manuscripts contain. Well, until now.

Slavomír and I have obtained copies of almost all of the manuscripts in Graf’s list, not an easy task given that some are described incorrectly or inadequately, and we were able to add to it five more (see pp. 113–15 of The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition for this provisional list). As it turns out, not all of the manuscripts contain Arab. Gos. Inf. after all. In the end, there are at least six manuscripts in the form edited by Sike (Recension S, a shorter text that includes Infancy Thomas), only one in the form edited by Provera (Recension L, which lacks Infancy Thomas but continues past the childhood to include a number of chapters summarizing canonical stories from Jesus’ adulthood), and two in a form that is unpublished (Recension P, which lacks both Infancy Thomas and the adulthood stories). A further five are pending evaluation, either because we are still waiting for copies or, in the case of one of them, it’s too bloody difficult to read! Four of the manuscripts we gathered actually contain the Apocryphal Gospel of John, and one other curious manuscript features a text by the name of “some of what was explained from the gospel of the infancy which we find said in some of the Syriac manuscripts.”

Our initial goal in working with this material was to contribute a new English translation of the “Gospel of the Infancy” to the next volume of New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. But we are still unsure of how to proceed. Do we favor the Syriac text, essentially extracting the infancy material from the larger History of the Virgin that is paralleled in Arab. Gos. Inf.? That solution assumes that Hist. Vir. and Arab. Gos. Inf. are two independent witnesses to a Syriac infancy gospel. What if, instead, Arab. Gos. Inf. is an extraction from Hist. Vir.? If so, there never was a Syriac infancy gospel. There are other problems also, not the least of which is that Hist. Vir.’s parallels to the Protevangelium of James are far more expansive than those in Arab. Gos. Inf. Does this mean that Hist. Vir. expanded the original infancy gospel with further material from Prot. Jas., or that Arab. Gos. Inf. reduced it? And what do we call the text? Arab. Gos. Inf. has become the standard title, but it is misleading and has contributed to the neglect of the Syriac text. If we call it Gospel of the Infancy, do we risk it being accidentally overlooked by subsequent scholars and bibliographers?

These concerns are not unique to the Gospel of the Infancy. Scholarship in our field is littered with nomenclature that has long outlived its suitability (consider the case of Prot. Jas. which has been given a title that is not found in any of the manuscripts and was adopted to reflect its first editor’s view that it predated and was a source of the canonical infancy narratives) . We hope that our paper will start a robust discussion about how other scholars can address similar problems in their own work.

For more information on the Arabic Infancy Gospel and the East Syriac History of the Virgin, look them up on e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha.

Wow, now let me guess, because the Infancy Gospels (in all languages) were unavailable to Mohammed (saw) and events in them are in the Qur’an the ARABIC version is singled out!

It’s a CHRISTIAN DOCUMENT!!!

Does it deserve to be attacked!?!?! Are you so afraid of the growth of Islam you’ve taken to attacking Christian literature now!!!

Just like Canonical Christian literature MSS differ im content.

Why is it so important that Apocryphal Infancy Gospels do? So does every book in both genres, no tradition is perfectly preserved.

The Qur’an alone has this unique aspect, to the letter.