Finding Jesus Episode 4: The “Secret Brother of Jesus”

The fourth episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery examines the contentious ossuary of James, the brother of Jesus, which David Gibson (author of the companion book to the series) calls the “first physical evidence that Jesus of Nazareth existed” (I guess they are already discounting the Shroud of Turin from episode 1). The episode was fair and balanced in its presentation of the evidence for the authenticity of the ossuary and, to my delight, mentioned several apocryphal texts in its piecing together of James’ biography. It was also nice to see them open the episode with shots of the Toronto skyline for their introduction to the ossuary—the artifact made its debut at the Royal Ontario Museum in 2002, the only time it has been on display.

The episode is entitled “The Secret Brother of Jesus.” While the existence of James may be news to some Christians who do not read the Bible, it is certainly no secret. James is mentioned as one of four brothers, and two sisters, in Mark 6:3 and Matthew 13:55 and he features prominently in Acts and the letters of Paul, and of course is author of his own New Testament letter. But if Jesus’ mother Mary was a virgin, where did these siblings come from? Protestants have no issue with the idea that Mary had children with Joseph after the virginal birth of Jesus; but Roman Catholics do not take the Gospels’ mention of them as “brothers and sisters” literally and identify them instead as cousins; and Orthodox Christians see them as children of Joseph’s previous marriage (a position advocated in the documentary, strangely enough, by the Roman Catholic priest Father James Martin). The Orthodox position is reflected in the Protevangelium of James, a late second-century apocryphal gospel in which Mary is presented as a virgin before the birth of Jesus and after (her hymen is not ruptured by the birth of Jesus, who passes through her uterus as light) and the siblings are children of the aged widower Joseph. It is really unfortunate that Prot. Jas. was not brought into this discussion of the siblings, particularly since the text is credited to James.

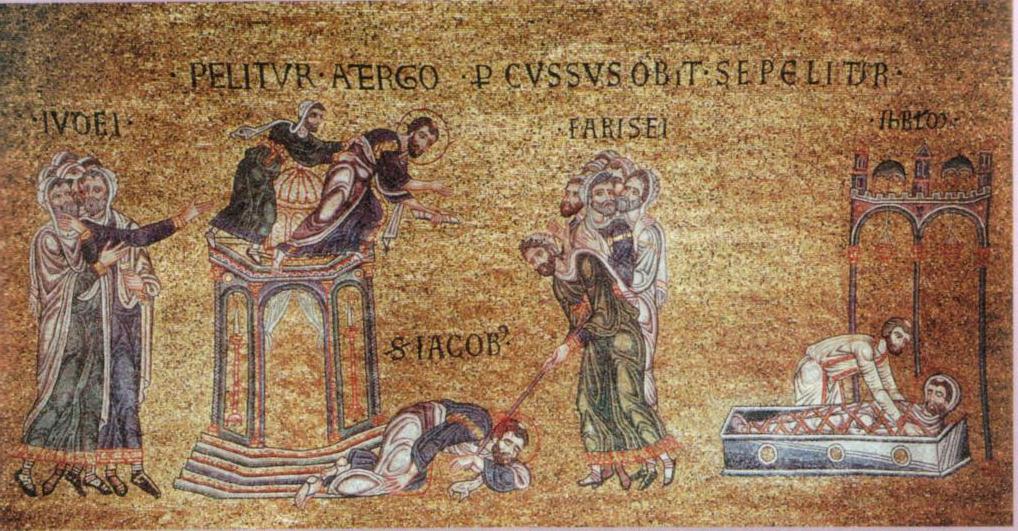

Image: a thirteenth-century mosaic depicting the martyrdom of James.

One apocryphal text that is mentioned is the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. The episode presented a dramatization of the story of James and the Snakebite from chap. 16 of the text. Jonathan Rowlands, a producer of the series, asked me about the story back in October. The plan at the time was to show a calligrapher writing the tale, but that scene never made it to the final cut. If I’m not mistaken, they used my translation (with some adaptation) of the episode for the narration. Rowlands asked me also, “Do you think the snake story tells us much about James’s role in early Christianity?” Unfortunately, I do not think it does. It just seems to be a vehicle for showing that Jesus was possessed of great power even as a child. Including James in the story just lends the account some verisimilitude.

The story of James continues with the death of Joseph, an event that is assumed to happen before Jesus’ ministry, though the Gospels do not explicitly say what happened to Joseph. As the eldest son (assuming, of course, that James and the other brothers are NOT children of Joseph from an earlier marriage), Jesus would be expected to take over Joseph’s role as the head of the family; instead, he begins his healing and teaching ministry, leaving James to fill that role. The contributors to the episode point out that this could have caused some friction in the family.

And perhaps this is why they come to see Jesus in Capernaum (Mark 6:19-21; 31-35 par.) and attempt to “restrain him” because he was “out of his mind.” In the documentary, this episode occurs right after the healing of the man with the withered hand (Mark 3:1-6 par.), though in Mark a great deal happens in between: the Pharisees begin their plot against him, Jesus draws great crowds, then he goes up on a mountain and there selects his twelve apostles). The narrator says only, “the crowds he attracts bring him to the attention of the Roman authorities,” and Roman soldiers are depicted, watching the crowds around Jesus nervously; it is doubtful, however, that soldiers would be stationed in Galilee at all.

Then the narrator says, “fearing for Jesus’ safety, James and his family come to Capernaum.” The Gospels say nothing about this justification. So there is certainly some creative license going on here in piecing together James’ relationship to Jesus. In a Facebook comment about the liberties taken in the documentary, series advisor Mark Goodacre said, “Within the documentary format, I think that generating a compelling narrative is important, and one uses the narrative as a means of inviting people into the discussion.” However, I think many scholars who watch the series bristle at the choices made to construct that narrative, particularly if they misrepresent the primary sources.

An episode from the Gospels not mentioned, but helpful in the argument that James did not support Jesus’ ministry, is John 7:2-5, in which Jesus’ brothers, who are said not to believe in him, urge him to go to Jerusalem and perform miracles.

Additional CA texts are brought into the discussion of the resurrection. Bruce Chilton mentions the Gospel of the Hebrews and how it places James in Jerusalem directly after the crucifixion. Chilton then says that, “James goes on a period of fasting and morning, something none of his followers did.” This seems to be a reference to Gos. Heb., which states, “James had sworn that he would not eat bread from that hour in which he had drunk the Lord’s cup until he should see him risen from among them that sleep,” though there is no reason to believe that other family members and apostles would not have done the same, and I think one needs to be careful about using Gos. Heb. to reconstruct James’ biography. Surprisingly, the resurrection appearance story from Gos. Heb. is not mentioned; instead the narrator reads from 1 Corinthians 15:4-7—why quote a noncanonical text when a canonical text reports the same facts, I suppose. Chilton later mentions another CA text, the Gospel of Thomas, with its apparent support of the leadership of James (based on logion 12).

The next major act in James’ life is the agreement that he makes with Paul over evangelizing Gentiles. The dramatization of the Jerusalem Council, based on Acts and Galatians, features a very nervous looking James and an arrogant Paul. James’ acquiescence to Paul’s mission is somewhat simplified—no mention is made of James’ demand that Paul’s Gentile converts follow the Noahide Laws (from Acts 15:20) nor of his command to Paul to “remember the poor” (Galatian 2:10), and both Acts and Galatians give the reader the impression that the Jerusalem church is dismissive of Paul (certainly they don’t seem to support his mission for very long).

The documentary makes this development in the church as the reason for James’ execution—the narrator says James is “now seen as a threat.” His martyrdom is then presented largely as it is recorded in Eusebius (Hist. eccl. 2.23): he is thrown from the pinnacle of the temple and then stoned. Eusebius actually presents three versions of the death of James, with differences between them: he reports that Clement of Alexandria says he was thrown down and then beaten with a club, that Hegesippus says he was thrown down, stoned, and then beaten with a club, and that Josephus says only that he was stoned. We have two additional accounts of the martyrdom of James in 1 Apocalypse of James and 2 Apocalypse of James from the Nag Hammadi library. In 1 Apoc. Jas. he is merely stoned, but 2 Apoc. Jas. is much more detailed: James is thrown from the pinnacle, then he is beaten, a stone is placed on his abdomen, then the crowd trample him with their feet, and finally he is made to dig a hole and stand in it to his waist, thereupon he is stoned to death. The variety even in the early sources suggests that there are different traditions about James’ death. As for the fate of James’ body, only Hegesippus provides any detail—he says it was buried on the spot, which, if true, would undermine the authenticity of the ossuary.

The story of the James ossuary, its purchase by Oded Golan and the protracted forgery trial, is interweaved throughout the documentary. Evidence is mentioned both for its authenticity (the ancient patina found in the entire inscription) and for its forgery (Rollston on the different hand in the latter half of the inscription); all-in-all I was pleased by how evenhanded the discussion was. Bruce Chilton’s final words end the documentary on an irenic note: whether authentic or not, the ossuary has brought attention to an important figure in the early church. So too has Finding Jesus.

I checked out your biblical reference to John 7:2-5, because I had forgotten it. I was surprised to see that Jesus is portrayed as lying to his brothers:

“Go to the festival yourselves. I am not going to this festival, for my time has not yet fully come.”

“But after his brothers had gone to the festival, then he also went, not publicly but as it were in secret.”