Finding Jesus Episode 1: Giving in to the Apocryphal Urge

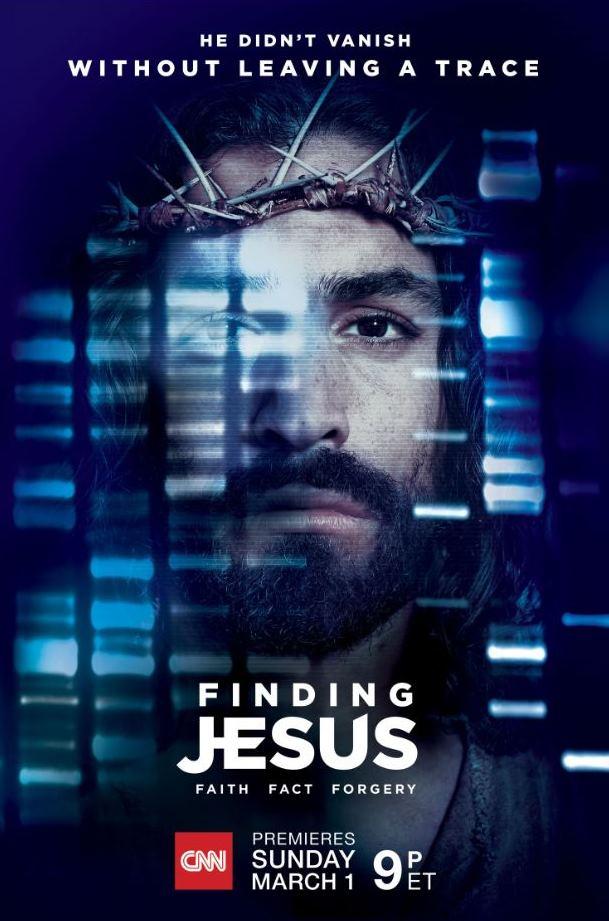

Last Sunday night, I tuned in, along with over a million other viewers, to the first episode of CNN’s six-part series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery. The series seeks to answer questions about the life and death of Jesus using evidence from artifacts—some textual (the Gospel of Judas) some not (the bones of John the Baptist). This first episode focused on the Shroud of Turin as possible evidence for Jesus’ death—indeed perhaps also his resurrection, given the Shroud’s apparent miraculous qualities. My interest in the episode is in how it demonstrates the apocryphal urge—meaning, the temptation to retell stories from early Christian texts, thereby harmonizing disparate accounts and adding new details until a new account is created, sometimes even supplanting the original stories in the minds of readers (or viewers).

Of course, not all apocryphal texts work this way; some contain entirely new material. But some of the most well-known apocrypha do repurpose and enhance older works, such as the Protevangelium of James’ use of the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke or the Gospel of Peter’s combination of elements from all four canonical passion narratives. The example of the Gospel of Peter is particularly useful here because, in its dramatic re-enactments of the suffering and death of Jesus and its commentary by participating scholars, authors, and theologians, Finding Jesus has created, perhaps unwittingly, a new account of the Passion that undiscerning viewers may think is biblically accurate but instead contains numerous elements not found in the canonical Gospels.

Of course, not all apocryphal texts work this way; some contain entirely new material. But some of the most well-known apocrypha do repurpose and enhance older works, such as the Protevangelium of James’ use of the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke or the Gospel of Peter’s combination of elements from all four canonical passion narratives. The example of the Gospel of Peter is particularly useful here because, in its dramatic re-enactments of the suffering and death of Jesus and its commentary by participating scholars, authors, and theologians, Finding Jesus has created, perhaps unwittingly, a new account of the Passion that undiscerning viewers may think is biblically accurate but instead contains numerous elements not found in the canonical Gospels.

New Testament scholars and those who read their Bible carefully know that the canonical Gospels often disagree with one another on the details of events in the life of Jesus. The urge to harmonize these accounts was born when Christians began to value and circulate multiple gospels. Finding Jesus gives in to this same urge; this is apparent whenever the narrator or the commentators state “the Bible tells us” or “the Gospels say.” In its telling of the burial of Jesus, the documentary mostly draws upon the Gospel of John, but elements from the Synoptic Gospels also enter into the story. The narrator states that Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus took Jesus down from the cross, washed the body, wrapped it in a linen cloth, and placed it in a tomb. All four gospels mention the burial cloth brought by Joseph, but only John adds Nicodemus to the story, and only in John do Joseph and Nicodemus prepare Jesus’ body (in the Synoptics, he is laid in the tomb and the women come days later to properly anoint him). The narrator of Finding Jesus states that Joseph was “a wealthy member of the Jewish Council, the Sanhedrin” but the Gospels vary in their descriptions of Joseph: “a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one” (John 19:38); “a rich man from Arimathea…also a disciple of Jesus” (Matt 27:57); “a respected member of the council, who was also himself expectantly waiting for the kingdom of God” (Mark 15:43); “a righteous man” and “a member of the council” (Luke 23:50). In effect, Finding Jesus has combined Matthew’s wealthy man with Mark and Luke’s council member. The documentary also states that Jesus was placed in Joseph’s tomb, but, again, the Gospels differ on this point: only in Matthew is it said that the tomb was Joseph’s (Matt 27:60), whereas in John it is simply a tomb in a nearby garden (John 19:41), in Mark “a tomb that had been hewn out of rock” (Mark 15:48), and in Luke “a rock-hewn tomb where no one had ever been laid” (Luke 23:53). Now, I understand that the documentary-makers have to simplify the story; they cannot spend all of their time comparing the gospel accounts as I have done. And to be fair, these harmonizations do not stretch historical credibility—for example, it may have been customary for council members to be chosen from wealthy families.

But what about elements brought into the story that are not found in the canonical Gospels, nor in any account of the Passion for that matter? Series advisor Mark Goodacre says in the episode, “the gospels describe Joseph of Arimathea as being a sympathizer with the Jesus movement. He’s fascinated with Jesus; so fascinated that even after the crucifixion he wants to make sure that the right thing is done, that Jesus gets the right burial.” Goodacre is certainly embroidering here; the Gospels say nothing about Joseph’s “fascination” with Jesus, nor the motives behind his desire for Jesus to get a proper burial. The episode then continues with a dramatization of a nervous Joseph asking a raving Pilate for the body of Jesus—something that happens “off-camera” in the Gospels.

The embroidery continues with the depiction of the scourging of Jesus. The canonical Gospels say very little about this incident. John says, “Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged” (19:1); later the crown of thorns is placed on his head and the soldiers strike him on the face (19:3). In Luke, Pilate plans at first to “have him flogged and then release him” (23:22), but the crowds call for his crucifixion; the gospel writer never explicitly says Jesus was flogged. All three Synoptics include the crown of thorns and remark that the soldiers spit on Jesus. And in Matthew and Mark, the soldiers take a reed and hit Jesus on the head (Mark 15:19; Matt 27:30). From this bare information, Goodacre states that Jesus suffered “the most appalling flogging; flogging that would have brought Jesus to within an inch of his life—a really appalling spectacle when you think about it.” But what is the basis for this? Could Goodacre’s comments and the accompanying gruesome dramatization be influenced by Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, which was the first Jesus film to depict the flogging in such grisly detail? Though Gibson’s film has been heavily criticized by scholars, perhaps it was so successful in avoiding the “sanitizing” (to use Goodacre’s term) of the Passion that its brutal flogging scene has become now an accepted element of depictions of the story. Gibson’s choice to follow the traditional stations of the cross—complete with Jesus carrying the entire cross and the inclusion of all of his final words, pulled from all four of the Gospels—may also have influenced the Finding Jesus filmmakers to include these same elements. One final point: Goodacre shows a flair for the dramatic when he says “they pressed [the crown of thorns] into his head so that you see blood trickling down his face.” Where do we “see” this? Certainly not in the New Testament Gospels, which only mention the soldiers placing, not pressing, the crown upon Jesus’ head.

Finding Jesus turns next to the crucifixion. Theologian Obery Hendricks (Columbia University) provides much of the context for this sequence, but some of what he says cannot be found in the New Testament Gospels. When Jesus arrives at Golgotha, Hendricks says, “they throw him on the ground; they’re talking to him as roughly as possible, and they’re showing him that he has no control at all. He has no protection.“ Jesus then lies down upon the cross, “and he sees this big spike,” Hendricks says, “and they’re holding his arm out and he’s straining to pull his hand away and they strike!” The accompanying dramatization depicts Hendrick’s every word. He continues: “then he’s raised up and imagine the agony of being raised up after your hands and feet are nailed in—every little movement is agony…the cross was lifted up by ropes and then dropped into a hole to keep it from falling. Imagine what that’s like!” The Gospels are quite silent on these details, so some imaginative reconstruction seems appropriate for bringing the story to life. Such embroidery is forgivable in film adaptations, because it is understood that filmmakers will add to the Gospel accounts; indeed, sometimes they have to. But for a theologian to do so in a documentary obscures the boundary between fiction and fact, so much that the average viewer may not be able to tell the difference. Another aspect of the crucifixion scene is altered in the documentary. Mary of Nazareth and Mary Magdalene are depicted as present at the cross. But in the Synoptics, the women (not including Jesus’ mother) just look on at a distance (Mark 15:40 par.); John does have the two women at the cross, but they are joined by Mary of Clopas and the Beloved Disciple (19:25).

Finally, one more scene is presented at the end of the episode. Joseph of Arimathea is depicted entering the tomb. He sees the burial cloths left behind by Jesus, gathers them, and then leaves the tomb. Of course, this scene has no biblical basis, but the documentary-makers are clearly speculating here about how the cloths could have been saved and then re-appear centuries later. Commentator Father James Martin provides the context at this point, saying, “it makes perfect sense to me that the cloths would have been preserved.” Why Joseph? Perhaps he was chosen to be the bearer of the Shroud since legend has it he was a steward of the Holy Grail. I wonder if viewers of the episode would make the distinction between this completely fictional scene and the other scenes that are based on the biblical accounts.

In sum, the Passion Narrative presented in Finding Jesus includes a brutal flogging of Jesus, a crown of thorns that draws blood, a 300 lb cross, a detailed depiction of Jesus being placed upon the cross, Mary of Nazareth and Mary Magdalene present at the crucifixion, the wealthy council-member Joseph and Nicodemus embalming Jesus and placing the body in Joseph’s tomb, Peter and John finding the burial cloths in the empty tomb (with no mention of the women), and Joseph of Arimathea taking the cloths and preserving them. It’s a compelling story, built on a selection of motifs from the canonical accounts, with additional details based on the documentary-makers’ (both the producers and the commentators) own particular interests, which, incidentally, are to tell a story that contains as many elements that correlate with the evidence of the Shroud as possible. This is precisely how texts like the Gospel of Peter were created. The same apocryphal urge is present today as it was in antiquity, and indeed throughout Christian history. It’s not certain, however, if the creators of these apocryphal accounts, ancient or modern, are aware that they are creating something new. Mel Gibson did not think so; he stated in interviews at the time of his film’s release that, “I’m telling the story as the Bible tells it.” But scholars have pointed out that The Passion of the Christ draws on the canonical gospels and non-canonical traditions, some invented by Gibson himself. Given that few Christians actually read the Bible, and viewers place some trust in the views of scholars, they may think that the Finding Jesus story is also “the story as the Bible tells it.” But it’s not. It’s a modern apocryphon. And it demonstrates quite effectively how apocrypha are developed.

Thanks, Tony, for your entertaining post. My thoughts in response are here:

http://ntweblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-apocryphal-urge-in-finding-jesus.html