Translating Joseph and Aseneth: My Role in Jacobovici and Wilson’s “Lost Gospel”

Last Monday morning a story appeared in the press, first in England but very soon all around the world, about a “lost gospel” that contains evidence that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene and had two children. You’ve probably heard something about it by now, and you may know I had a hand in this project—a book, The Lost Gospel: Decoding the Ancient Text that Reveals Jesus’ Marriage to Mary the Magdalene (Harper Collins, 2014) by Simcha Jacobovici and Barrie Wilson, and forthcoming documentary. The “lost gospel” of the title is a Syriac text: the Story of Joseph and Aseneth embedded in the chronicle of Pseudo-Zacharias Rhetor. I translated the text from two manuscripts at the British Library (one from the sixth-century and another from the twelfth). Since some people have been asking about the translation, and where I stand on the book’s argument, I thought I’d write something about my involvement in the project.

Last Monday morning a story appeared in the press, first in England but very soon all around the world, about a “lost gospel” that contains evidence that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene and had two children. You’ve probably heard something about it by now, and you may know I had a hand in this project—a book, The Lost Gospel: Decoding the Ancient Text that Reveals Jesus’ Marriage to Mary the Magdalene (Harper Collins, 2014) by Simcha Jacobovici and Barrie Wilson, and forthcoming documentary. The “lost gospel” of the title is a Syriac text: the Story of Joseph and Aseneth embedded in the chronicle of Pseudo-Zacharias Rhetor. I translated the text from two manuscripts at the British Library (one from the sixth-century and another from the twelfth). Since some people have been asking about the translation, and where I stand on the book’s argument, I thought I’d write something about my involvement in the project.

About six years ago Barrie Wilson, my colleague at York, asked me if I knew of an aspiring scholar with knowledge of Syriac who could translate a text for him. He meant me. Barrie was involved in hiring me at York ten years ago and we continue even today to interact, on thesis committees, etc., though now Barrie is retired. I was looking at the time for opportunities to exercise my Syriac skills. So, for both of these reasons, I had to say yes. I think Barrie told me then (if not, soon after) that Simcha was involved in the project. The two of them were careful not to reveal anything to me about their interpretation of the text; they said they did not want it to influence my translation. Of course, late in the process I started to have my suspicions but the full details were not revealed until long after I completed the translation.

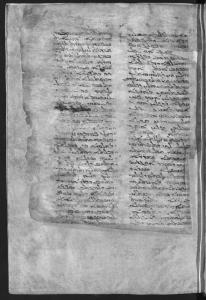

The Syriac text of Joseph and Aseneth is found in only two manuscripts: British Library, Add. 17202 (sixth cent.) and British Library, Add. 7190 (twelfth). These were published by J. P. N. Land in 1870 (in Anecdota Syriaca vol. 3. E. J. Brill)—i.e., Land gave a transcription of 17202 and added material from 7190, which appears to be a copy of the earlier manuscript, to fill in material from a missing page at the beginning of 17202. G. Oppenheim (Fabula Josephi et Asenethae apocrypha e libro syriaco latine versa. Berlin, 1886) later provided a Latin translation (with emendations of the Syriac text in his notes), and E. W. Brooks (Historia Ecclesiastica Zachariae Rhetori vulgo adscripta . CSCO, Scriptores Syri, III. v, Textus; Paris, 1919) presented a transcription and Latin translation of Ps.-Zacharias in its entirety. The Syriac text has never been translated into a modern language nor has it been used effectively in modern editions and translations of Joseph and Aseneth.

I worked for several months on the translation, with help at times from Slavomír Céplö, with whom I worked on the Syriac tradition of the Legend of the Thirty Pieces of Silver. I sent him chapters to look over and he provided solutions to the occasional troublesome word or phrase. I also had a little help from Albert Frey. The text is long but not particularly challenging.

Though my work was completed fairly early in the process, the publication of the book was continually pushed back—due, I think, to delays in filming the documentary and Simcha’s workload. In the meantime, I ordered copies of the manuscripts to check the transcription (which was wrong on rare occasions). Barrie and Simcha asked me at this time to translate the introductory correspondence to the text—a letter from an anonymous writer to Moses of Ingila, asking to translate the text from Greek and reveal to him its “inner meaning,” and Moses’ response. Again, Land had transcribed these letters and Brooks had re-transcribed and translated them into Latin. My own task of translation proved more difficult than for Joseph and Aseneth, due in part to damage to the manuscript: a portion of the bottom of one leaf is cut off and there is damage here-and-there to a number of words. In the end I managed to reconstruct and translate the text fairly well (with help again from the very talented Slavomir Céplö).

I think these letters are quite interesting. Here we have a third example of a thwarted promise of revealing the meaning of an apocryphal text. The other two are the manuscript of Clement’s Letter to Theodore, which ends abruptly with “Now the true explanation [of the Secret Gospel of Mark] and that which accords with the true philosophy,” and Eusebius of Caesarea’s excerpt of Bishop Serapion’s tract on the Gospel of Peter, which terminates before Serapion reveals the docetic contents of the text (see Hist. eccl. 6.12.1-6). Perhaps, in all three cases, someone has willfully censored the material due to sensitivity over its heretical contents.

The manuscript evidence for the Syriac Joseph and Aseneth allowed me to construct a timeline for the text’s transmission, which I passed on to Barrie and Simcha. 1. The text was composed in Greek at some point in the early Christian centuries (I do think that the text is Christian, not Jewish, or at least it has undergone some significant Christian re-working). 2. An anonymous writer sent the Greek text to Moses of Ingila in the sixth century, asking him to translate it into Syriac and reveal to him its “inner meaning.” 3. Shortly after, Ps.-Zacharias incorporated the text and the letters into his history in the middle of the sixth century, roughly the same time as the composition of British Library Add. 17202 (curiously, this is a short span of time for all of these elements of transmission to occur; could the anonymous writer be Ps-Zacharias? could Add. 17202 be the autograph of the chronicle?) . 4. This manuscript was used by the twelfth-century copyist of British Library Add. 7190. By this time the original manuscript had lost several leaves (thus chs. 13:12-16:3 are missing) but the beginning of the text and the letters were intact. However, the copyist of Add. 7190 chose not to reproduce the letters. 5. Sometime after the twelfth century, the final page of the letter and the first page of Joseph and Aseneth was removed from Add. 17202 and the bottom portion of Moses of Ingila’s letter was cut off, right where the “inner meaning” was to be revealed.

The final part of my story takes place in London. I was asked to take part in the filming of the documentary at the British Library. The timing wasn’t great: the shoot was scheduled just a few days after I was set to return from my honeymoon in Italy. But it seemed like a great opportunity—I’d never been in a documentary before, and I hadn’t been back to England since I emigrated to Canada when I was nine years old. Also sweetening the deal was the ability to visit the British Library and see the manuscripts in person. At the same time Simcha and Barrie commissioned some digital-imaging specialists to scan and analyze the manuscript. I was skeptical that this would yield much results. Typically multi-spectral imaging is used in very specific circumstances: to recover erased text (particularly in palimpsests) or to assist with deciphering pages that have become transparent, so that the writing on the other side interferes with reading. The results of the scanning were revealed a few months later and we reconvened for additional filming in a Toronto studio. As I suspected, the scanning was helpful in a few instances where the manuscript was difficult to read, but nothing remarkable was revealed.

Throughout the process Barrie and Simcha warned me that I might be criticized for working with them on the book; other scholars have shied away from participating on Simcha’s projects out of fear of damage to their careers, others because they worry that their views will be misrepresented, as often happens in documentaries. I think Barrie and Simcha’s decision not to tell me about their argument was motivated, at least in part, by a desire to prevent my scholarly reputation from being damaged. I am not one to shy away from controversy and believe that no argument—even if it is highly speculative, even if it is presented outside of scholarly circles—should be silenced. It has been frustrating to see other scholars and the media dismiss the book without having read it or fully engaged with its arguments. I don’t expect Barrie and Simcha’s position on Joseph and Aseneth to convince many on the origins of this text, but there are aspects of their work that are of interest for the study of Syrian Christianity.

All told, today we are talking again, scholars and non-scholars, about the historical Mary Magdalene, Jewish and Christian apocrypha, Syrian Christianity, and Syriac manuscripts. And we have Barrie Wilson and Simcha Jacobovici to thank for that.

I am sorry to hear that you have been criticised. I would have done the same as you did; and I differ from them more than most. I think that everyone acted rightly in this matter, from what you say. They didn’t impose their theory on the text – unlike the recent revisers of the NIV – and you didn’t endorse it.

I don’t subscribe to the idea that cranks can never be of use. In this case they will stir up interest in an otherwise obscure text. Would you ever have done that work otherwise? So we all benefit.

Cranks come and go and are forgotten. But, if we can hold our noses, then perhaps there are things of permanent value to be gained.

I think you have done rightly.

I am grateful to you for translating the Syrian text of Joseph and Aseneth because it offers me a great deal to add to my research of the earliest Gnostic Christian movements during the 1st through 3rd centuries. The story seems divinely inspired and many parallels can be drawn with Valentinian gnostic tenets, specially the bridal chamber mystery which I write a great deal about. Of course, these similarities also point to an early Hellenistic Jewish mystical tradition.

I am not ready to conclude anything about the origins of the text, whether it is Jewish or Christian. Thank you for writing this disclaimer. I am now sure I can trust the translation as accurate, because after fact checking Jacobovici and Wilson’s analysis and research I found too many problems of shallow research, parallels drawn where no real parallel exists, and deliberate omissions of lines in referenced material which were purposely crafted to mislead the reader into accepting his conclusions. I am just finishing up the book. If you are interested in an amazing discovery I made pointing to a Gnostic Mary Magdalene tradition in the middle ages I invite you to read my blog and to read my book. http://gnosticmarymagdalene.blogspot.com

Thanks so much for your candid and thorough account. I for one plan to actually READ the book before I review it and I hope other conscientious colleagues will do the same, not matter what their attitude toward “Simcha” might be–who seems to be a red flag waving to same. I appreciate even more the translation you provided. What a great service you have rendered all of us, regardless of various and varied interpretations of the text. Many thanks Tony for all you have done!

Tony, I appreciate your reflections. I am saddened that people would be vilifying you for your role in this matter.

I read and translate Syriac and Greek texts myself, and have a question. Jacobovici and Wilson see in 4:11 an analogy to Jesus sweating blood (Luke 22:44). I don’t see it myself. Blood is not mentioned. I would read the text as saying Aseneth is red in the face from extreme emotion and also sweating as a result. What do you think?

Eventually I will have more questions, no doubt, and would love to talk with you about the text if you are so inclined.

Thanks for the comments. But I must clarify: I have not been “vilified” or “criticized” for my role in the book, though this was Simcha’s and Barrie’s concern.

I’ve been following the storm over the book, and that’s how I got to your site. Reading your blog and the responses reminds me of the Spaghetti Western, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”.

The “Good” are clearly Simcha and Barrie. According to your post, they commissioned the first ever translation of Joseph and Aseneth, i.e., the Syriac version. I also assume they paid for this, so they put their money where their mouth is. Furthermore, they commissioned the translation of the two letters attached to the manuscript. But it seems they didn’t stop there. They commissioned multi-spectral photography which restored the text and confirmed – according to interviews I read – that the act of censorship was, indeed, censorship. This revelation alone adds to the small body of censored texts that you’ve been studying. What’s particularly interesting about what you write is that they didn’t interfere with your translation work, nor did they tell you their theories so as not to prejudice your scholarship. Wow. For a finale, they provided a scholarly book interpreting what you call an “early Christian” text.

Now for the “Bad”: the bad are clearly critics like Roger Pearse above. I doubt that he read the book, but he already attacks both Simcha and Barrie personally. He calls them “cranks”, for reasons which he does not elaborate, and then, when he praises your work that they commissioned and published, he does so while “holding his nose”. Mr. Pearse, I had to hold my nose when I read that.

Now for the “Ugly”: the ugly is, unfortunately, your blog. Not because you’re ugly, or anything that you said is particularly ugly, but because it reveals something very ugly about the current state of Biblical scholarship. What’s ugly, Dr. Burke, is that you have to be *so* careful. Even though you admit that Simcha and Barrie have worked for years researching and writing their book, commissioning your translation, not interfering with your work and acting as a catalyst for a worldwide discussion about texts that the majority of the planet have never heard about… You’re nearly apologetic about your involvement. You didn’t have to give multiple reasons for why you participated in the documentary and went to the British Library. Seeing the manuscript – on a trip that was probably subsidized – is reason enough. What it shows me is that you’re walking a fine line, trying to distance yourself from Simcha and Barrie while not betraying them and maintaining the respect of your colleagues so as not to become the butt of their jokes. It seems you’ve succeeded. The above commentators are praising you while mocking Simcha and Barrie. What an ugly state of affairs. More appropriate to scholarship in the former Soviet Union, where I was born, than in free democracies.

Hi Tony –

Your students should be warned that by reading and studying the Apocrypha, they are entering dangerous territory. Christians from minority communities, for whom the works of the Apocrypha were treasured scriptures, were killed by the majority Christians, especially in the 4th and 5th centuries after emperors Constantine and Theodosius favoured one faction — Pauline Christianity — over all others. As you and your students know well, early Christianity of the first 3 centuries was incredibly diverse. Many minority Christians who wrote and read the texts you and your students are studying paid for their views with their lives.

Majority Christian intolerance has surfaced from time to time over the years – for example, the killing of thousands of Cathar Christians, the Inquisition, the Catholic Index as well as book burnings in various countries in the 19th and 20th centuries.

We see the same book burning/banning impetus at work today as some bloggers with various personal agendas tried to stifle scholarship and media coverage, especially ones who weighed in prior to the book’s release and who therefore could not have read the evidence. That, too, is instructive and a lesson in how scholarship should, and should not, be conducted.

Barrie

1) Thanks for your account of your role and for your translation.

2) The publisher, I think, is not Harper Collins but Pegasus Books.

3) Is it fair to say that the Syriac mss have not “been used effectively” by scholars, e.g., Christoph Burchard?

4) Would it be fair to say that the proposal that “Clement’s Letter to Theodore” was “perhaps” censored involves some very big ifs?

5) Thanks for noting that some worry about views being “misrepresented, as often happens in documentaries.”

6) Would you care to comment on Richard Bauckham’s argument against the censorship proposal, as published at Mark Goodacre’s NT Blog, either here or there?

Stephen, the book is published by Harper Collins in Canada (so my copies say Harper Collins, and that’s what counts!). I’d like to respond to your other questions but I am at SBL in San Diego for the rest of the week–where the weather is good but the Wifi is terrible. So, I’ll get back to this when I return.

@“Tony” — November 23, 2014 at 4:44 pm

Were you swallowed by the SBL in San Diego, Dr Burke ?…

Richard,

Yes! It’s the end-of-term so my time is taken up with classes, thesis defenses, etc. I will read Bauckham’s critique of The Lost Gospel as soon as I am able. For now, let me get back to Stephen’s other questions:

3. I think so. Burchard dismissed the Syriac tradition in his magnum opus of the text. And he may have good reason to do so (I have not seen his comments), but the Syriac text is very early. At the very least it should have been translated into a modern language well before now.

4. That depends what your “ifs” are. I think the arguments for authenticity are fairly strong. How about, if you agree with the evidence that indicates Smith did not and could not have created the text, and if you think it pre-dates the 18th-century copyist who wrote it in the back of the Voss book? Now, it may not have been written by Clement of Alexandria, but that doesn’t preclude someone (even if that someone was the 18th-century copyist) from editing (perhaps censuring is too strong) the letter due to sensitivity to its interpretation.

5. I worry about this too.

6. I will try. I promise.

@“Tony”— December 8, 2014 at 10:03 am

I’m nothing else, Dr Burke, than Stephen Goranson’s Comments guardian angel in this Wild World :-(.

Haven’t yet read Pr Bauckham’s Seven Articles ? Have a look at my highlighted version of his Part 1 – a very few typos in it…

@“Tony”— December 8, 2014 at 10:03 am

« 6. I will try. I promise. » : Don’t worry, Mr Goranson, I’m here…