The 2013 York Christian Apocrypha Symposium in Retrospect: Part One

This year’s York Christian Apocrypha Symposium is now fading into memory. I have stopped waking at night thinking that David Eastman is stranded in an airport, or Jean-Michel Roessli is endlessly circling Toronto Island on a boat. Other bloggers (Sarah Veale and Mark Bilby) have offered their thoughts on the event. So, I think it’s time I presented by own post mortem analysis.

(Front row, left to right: Lily Vuong, Stephen Shoemaker, Charles Hedrick, Mary Dzon, Stanley Jones, Mark Bilby. Second row: Pierluigi Piovanelli, Lee Martin McDonald, Annette Yoshiko Reed, Jean-Michel Roessli, Cornelia Horn, Stephen Patterson, Tony Burke, David Eastman. Back: Kristian Heal, Mark Goodacre, Glenn Snyder, Lorenzo DiTommaso, Brent Landau, Nicola Denzey Lewis, John Kloppenborg)

The York Christian Apocrypha Symposium series began in 2011 with a one-day event focusing on a single text: the Secret Gospel of Mark. We gathered together eight North American scholars and one editor of Biblical Archeology Review to discuss the text in front of an audience of about 60 people. The papers were published in early 2013 as Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery? The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate. The budget for this first Symposium was small but it was a seminal event, a beginning to the forming of an association (if informal) of North American scholars of the Christian Apocrypha.

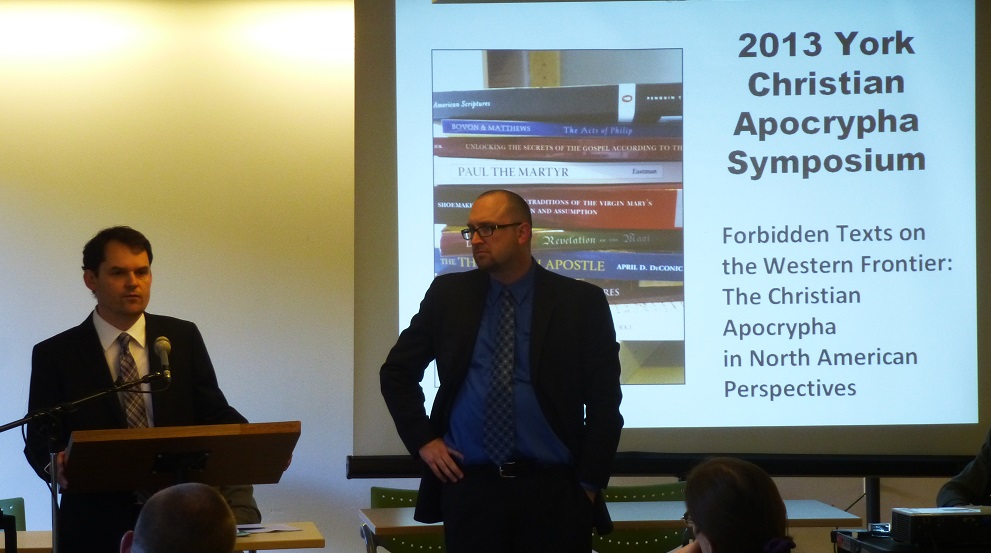

The success of the first Symposium enabled us to aim higher for the second. This time we gathered 19 scholars for presentations taking place over two days. Everything was improved: a swanky reception, better accommodations, decent meals, and more coffee and snacks. The planning for the event began about a year ago. I brainstormed with my frequent collaborator Brent Landau (University of Texas) over possible topics and presenters. We settled on a “state-of-the-art” for CA studies in North America, calling it “Forbidden Texts on the Western Frontier: The Christian Apocrypha in North American Perspectives.” Admittedly, the topic was less sexy than focusing on a single controversial text like Secret Mark, but it turned our attention to the primary goal of the Symposium series: to strengthen and expand the field of CA studies in North America. We were pleased that virtually everyone we asked was willing to participate and we put together a well-balanced lineup of Canadian and US scholars at various stages of their careers (junior, mid-career, and senior). Two had to pull out of the event, Janet Spittler and Phil Tite, but Glenn Snyder and John Kloppenborg graciously stepped in as replacements.

The success of the first Symposium enabled us to aim higher for the second. This time we gathered 19 scholars for presentations taking place over two days. Everything was improved: a swanky reception, better accommodations, decent meals, and more coffee and snacks. The planning for the event began about a year ago. I brainstormed with my frequent collaborator Brent Landau (University of Texas) over possible topics and presenters. We settled on a “state-of-the-art” for CA studies in North America, calling it “Forbidden Texts on the Western Frontier: The Christian Apocrypha in North American Perspectives.” Admittedly, the topic was less sexy than focusing on a single controversial text like Secret Mark, but it turned our attention to the primary goal of the Symposium series: to strengthen and expand the field of CA studies in North America. We were pleased that virtually everyone we asked was willing to participate and we put together a well-balanced lineup of Canadian and US scholars at various stages of their careers (junior, mid-career, and senior). Two had to pull out of the event, Janet Spittler and Phil Tite, but Glenn Snyder and John Kloppenborg graciously stepped in as replacements.

The months of planning reached their fruition Wednesday and Thursday (September 25 and 26) with the arrival of the participants to the campus. Two students (Sarah Veale and Joe Oryshak) and I shared the chauffeuring duties, but several rescheduled flights meant that a few of the participants had to procure taxis. A few others arrived by train, car, even boat. By 7 pm most everyone had made it to campus and we gathered for a reception. Drinks and hors d’oeuvres helped the conversation flow and everyone had a chance to catch up with old friends and make new ones.

The months of planning reached their fruition Wednesday and Thursday (September 25 and 26) with the arrival of the participants to the campus. Two students (Sarah Veale and Joe Oryshak) and I shared the chauffeuring duties, but several rescheduled flights meant that a few of the participants had to procure taxis. A few others arrived by train, car, even boat. By 7 pm most everyone had made it to campus and we gathered for a reception. Drinks and hors d’oeuvres helped the conversation flow and everyone had a chance to catch up with old friends and make new ones.

The true work of the Symposium began Friday morning with our first session, “Christian Apocrypha in the 21st Century.” The presenters were asked to provide a draft of their papers to all those who attended; unfortunately, many were unable to do so, which meant that the precise contents of many of the papers were a mystery, even to me, though Brent and I did guide the presenters toward certain topics. Jean-Michel Roessli (Concordia University) was asked to discuss “North American Approaches to the Study of the Christian Apocrypha on the World Stage.” He discussed the origins and scholarship of l’ AELAC, an organization with which many of the scholars in the room are involved, and the impact of the group’s work on North American scholarship, particularly via François Bovon at Harvard. Roessli took a bit of a detour at the end of the paper, urging us to examine the origins of the discipline in the Enlightenment, which began a discussion of the “apocryphal canon” (that is, how apocryphal texts are selected for inclusion into scholarly collections) that many touched upon over the weekend. Pierluigi Piovanelli (University of Ottawa) followed with “Trajectories through Early Christianity and Late Antiquity: The longue durée of Christian Memorial Traditions in American Scholarship,” another informal discussion that focused on recovering early traditions from late apocrypha. Pierluigi used the example of his work on the Book of the Rooster (wisely renamed from its former title, “Book of the Cock,” a move which elicited giggles from the audience). Then he surprised everyone with an announcement of a new apocryphal text in Ethiopic. This text is a brief summary of a vision of the flogging and crucifixion of Jesus (in grisly Mel Gibson-like detail) to the three women at the tomb. As it turns out, however, the text is actually a medieval devotional text which originally featured three medieval female saints as the visionaries. Though it did not begin as an apocryphon, it was transformed into one by a later scribe.

Brent Landau then presented on “The ‘Harvard School’ of the Christian Apocrypha,” which has become well-known (and much-criticized) for its resistance to favouring canonical over non-canonical texts for their historical and literary qualities. Though Harvard is most well-known through the works of Koester, Bovon, and Karen King, Landau mentioned some important events of the Harvard school’s prehistory in an 1838 address by Ralph Waldo Emerson and a collection of agrapha made by James Hardy Ropes in 1896. Landau noted the impact of the Harvard school on the field in North America, particularly through those who, like himself, graduated from the program. But he lamented also that the future of the school is uncertain—Koester is still teaching (in his 55th year at Harvard!), but Bovon and King have had very serious illnesses in recent years and none of the present junior faculty have the CA as a chief research interest.

Brent Landau then presented on “The ‘Harvard School’ of the Christian Apocrypha,” which has become well-known (and much-criticized) for its resistance to favouring canonical over non-canonical texts for their historical and literary qualities. Though Harvard is most well-known through the works of Koester, Bovon, and Karen King, Landau mentioned some important events of the Harvard school’s prehistory in an 1838 address by Ralph Waldo Emerson and a collection of agrapha made by James Hardy Ropes in 1896. Landau noted the impact of the Harvard school on the field in North America, particularly through those who, like himself, graduated from the program. But he lamented also that the future of the school is uncertain—Koester is still teaching (in his 55th year at Harvard!), but Bovon and King have had very serious illnesses in recent years and none of the present junior faculty have the CA as a chief research interest.

The final paper of the first session, Charles Hedrick’s “Excavating Museums: From Bible Thumping to Fishing in the Stream of Western Civilization,” was circulated in draft form, so Hedrick was able to briefly summarize the paper thereby allowing more time for discussion. The paper is a scholarly autobiography, touching on several major discoveries in which Hedrick played a part, including the publication of the Gospel of Judas and the Gospel of the Saviour. Hedrick also mentions in the paper the conflict he had with studying apocryphal texts while being much involved in the Southern Baptist Church (he even served as pastor at several points in his early professional career). He concluded as a graduate student that, “in historical scholarship it is not possible to be a servant of the church and the discipline at the same time” particularly because “non-canonical literature presents a threat to the church.” Not everyone in attendance agreed that a decision has to be made between church and scholarly study, but even today there have been some nightmare stories out of the US of biblical scholars losing their positions because their work conflicts with the mandate of their institutions. The interplay between faith and historical investigation was another topic that we returned to over the course of the weekend.

The final paper of the first session, Charles Hedrick’s “Excavating Museums: From Bible Thumping to Fishing in the Stream of Western Civilization,” was circulated in draft form, so Hedrick was able to briefly summarize the paper thereby allowing more time for discussion. The paper is a scholarly autobiography, touching on several major discoveries in which Hedrick played a part, including the publication of the Gospel of Judas and the Gospel of the Saviour. Hedrick also mentions in the paper the conflict he had with studying apocryphal texts while being much involved in the Southern Baptist Church (he even served as pastor at several points in his early professional career). He concluded as a graduate student that, “in historical scholarship it is not possible to be a servant of the church and the discipline at the same time” particularly because “non-canonical literature presents a threat to the church.” Not everyone in attendance agreed that a decision has to be made between church and scholarly study, but even today there have been some nightmare stories out of the US of biblical scholars losing their positions because their work conflicts with the mandate of their institutions. The interplay between faith and historical investigation was another topic that we returned to over the course of the weekend.

To be continued…