Reflections on the Material of Christian Apocrypha Conference: Part II

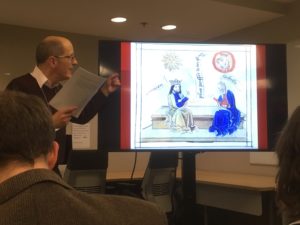

Day two of the “Material of Christian Apocrypha” conference was all about the Great White North as the Canadians took over the podium. First up was Jean-Michel Roessli (Concordia University) with “The Tiburtine Sibyl and the Legend of the Aracoeli, aka the Vision of Augustus.” The Tirburtine Sibyl is not a widely known text, but, in Stephen Shoemaker’s words, for medieval Christians its “influence on Christian eschatology far outweighed that of the Apocalypse of John” (MNTA 1:513). It is one of a number of texts—including the Legend of Aphroditianus and a few excerpts I am working on from the Syriac Sayings of Greek Philosophers—that demonstrate knowledge of Christ’s birth or death among people in the wider Greco-Roman world. The focus of Roessli’s paper is a tradition in which the Sibyl is asked by the emperor Augustus who will succeed him and he is told of a “Hebrew child, God ruling over the blessed.” John Malalas (491–578) may be the earliest witness to this tradition; his Chronography (X.5) features the same exchange but adds that Augustus set up an altar (the Ara coeli) in the bedchamber of his palace on the Capitoline on which is written “This is the altar of the first-born God.” Later a basilica was built on the site, known today as the Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara coeli al Campidoglio.

Other writers mention the oracle and the location of the altar, but most significant is a development made prior to the time of Pope Innocent III (r. 1196–1216); in Innocent’s second Sermon, the testimony of the oracle has been changed into a vision of the Virgin with child. The inscription on the altar at the Basilica today reflects this change: “You who climb to this church of the Virgin, which was the first such site in the city, should know that Caesar Octavian has constructed this when from an altar in the heaven, the holy child is revealed to him.” In the Golden Legend, the vision is described as “at midday a golden circle appeared around the sun, and in the middle of the circle a most beautiful virgin holding a child in her lap.” And this is the image found in manuscript illuminations, particularly those found in copies of the Golden Legend, the Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation, a popular late medieval work on the life of Jesus and the Virgin), and in Books of Hours. Roessli’s presentation included a variety of these illuminations. But the most interesting iconographic depiction of the vision is found in the Bladelin Triptych by Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464) because it also includes a scene of the Magi looking up to a star in the form of a baby—a motif found in the Revelation of the Magi and the Book about the Birth of the Savior. Roessli mentioned also that the vision was included in medieval mystery plays, including the Elche Mystery Play, which is still performed today (and you can watch a performance in THIS CLIP from YouTube). For me, as for many Christian apocrypha scholars, Tib. Sib. has always sat on the periphery of my attention because it is short on narrative about Jesus and his contemporaries—some might argue that it is not truly a Christian apocryphon at all—but Roessli’s presentation really demonstrated the popularity of the Sibyl traditions. And the Vision of Augustus is an ideal topic for this conference, not only because of its documentation in a large number of manuscript illuminations but also because of its concrete (ahem) representation in the Ara coeli.

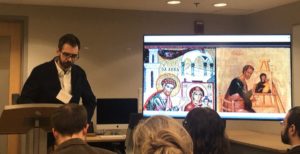

Bradley Rice (McGill University) followed Roessli with “The Story of Joseph of Arimathea and the Story of Icons in Christian Apocrypha: The Curious Case of the Icon of the Virgin at Lydda.” Likely few, if any, of the conference participants have ever heard of the Story of Joseph of Arimathea; it is extant today only in Georgian and Rice has contributed a translation of it to MNTA vol. 2. In the text Joseph recounts how he and other disciples built a church dedicated to Mary in Lydda. The synagogue of the city is torn down to make way for the church, leading to inevitable conflict with the Jewish community. The governor tries to settle the issue of who is the rightful user of the property by locking up the church for forty days and awaiting a sign. After the forty days, the doors are opened to reveal a painting of Mary. Rice connected this image with the Hodegetria, an image of Mary with the child Jesus said to have been painted by Luke and copied many times over the centuries. Some traditions combine these two images, so that Luke is said to have made the Hodegetria by copying the Lydda painting. A sanctioned copy of the Hodegetria made its way to Constantinople and Rice told the amusing story of how this copy was saved from the first wave of iconoclasm under Leo II by throwing it into the sea whereupon it swam to Rome and was displayed in Saint Peter’s Basilica. A century later it swam back to Constantinople. Story Jos. Arim. is an example of what Paul Dilly calls inventio literature: apocrypha created to “influence imperial policy and public opinion,” in this case to perhaps settle disputes over holy sites, though Rice thinks it is more likely that the text was intended more to argue for the eminence of the church of Mary over other Christian churches. It is also not the only text that uses a miraculous image of Mary to establish a church dedicated to Mary. A Coptic Homily on the Building of the First Church of the Virgin, attributed to Basil of Caesarea tells the story of the Virgin revealing the location of her buried icon and its placement on columns that miraculously float into a church consecrated by Peter and Paul in Caesarea Philippi. This text too is featured in MNTA vol. 2 in a translation by Dilley.

The final paper of the early morning session was delivered by Emily Laflèche, a graduate student at the University of Ottawa. In “Funerary Imagery in the Procession of the Seven Virgins Located in the Exodus Chapel at El-Bagawat,” Laflèche showed images from the chapel which is situated in one of the oldest Christian cemeteries (5th/6th cent.). The crude wall paintings include an image of Thecla being burned alive; a cloud hovers nearby, evoking the scene from the Acts of Paul 3:22 where Thecla is saved from martyrdom by rain that douses the flame. Another image on the wall features seven women bearing torches walking toward a building. They are labeled “virgins” and Thecla too is named, though someone in the past fifty years has covered over the writing. Opinions range over the identity of these virgins. Stephen Davis connects the two images and thinks this is a group of ascetic virgins dedicated to Thecla. Others have seen it as a representation of the seven virgins who work in the temple with Mary in Prot. Jas. 10. Laflèche compared the image to a representation at Dura Europos of 10 women holding torches and small bowls and walking to a building; some have said that this is a depiction of the 10 bridesmaids walking to the home of the bridegroom in Matthew 25:1–13 . Laflèche brought in another set of comperanda to help interpret the image: the descriptions of the ritual of the bridal chamber from the Gospel of Philip and the Pistis Sophia as well as two Valentinian funerary inscriptions (NCE 156 and the gravestone of Flavia Sophe). These sources mention light and torches, and the Pistis Sophia even specifies the presence of “seven virgins of the light.” Laflèche concluded that the interpretation of the El-Bagawat image need not be limited to one text but to a concept/practice that is alluded to in multiple sources. It may seem odd that a reference to a fairly obscure Christian ritual would show up in this church in the middle of the desert but the funerary inscriptions are just as surprising for the evidence they provide. Laflèche’s argument for Valentinian interpretation of the image is also a lesson, championed in our field, about being open to considering noncanonical influences when others see only canonical.

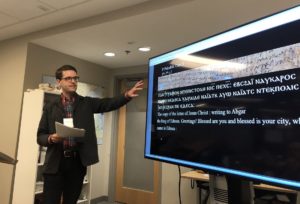

After a short break, two graduate students, Nathan Hardy (University of Chicago) and Gregory Given (Harvard University) delivered papers on the Abgar Correspondence traditions. Hardy was first with “‘He will illuminate you and lead you to all truth’: Transformations in Image and Viewer Between the Acts of Thaddeus and the Narratio de Imagine Edessena.” Most of us are familiar with the Abgar Correspondence reported by Eusebius, and its expansion in the Syriac Doctrine of Addai, but few are aware of the Greek transformation of Doctr. Addai into the Acts of Thaddaeus, and less still in the Narratio (this was my first exposure to it). The text tells of the translation of the image of Christ from Edessa to Constantinople in 944 and likely was written soon after; it is attributed to the emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus and was later incorporated into Symeon Metaphrastes’ Menologion—so it certainly was a widespread tradition in the Middle Ages. In Doctr. Addai, Abgar’s messenger Hanan paints an image of Jesus and brings it back to Edessa. Acts Thad. changes this so that the messenger (here called Ananias) cannot paint Jesus because of his dazzling brilliance; instead Jesus wipes his face with a cloth and his image is miraculously captured upon it. The same account is taken over into the Narratio but a sequel is added in which Ananias comes to Heliopolis and hides the cloth in a pile of tiles; fire comes out of the cloth and transfers the image to a tile which, the text reports, is still venerated in the town. The Narratio also reports another tradition about the creation of the cloth; in this one, preferred by Constantine, the image is made when Jesus sweats blood in Gethsemane (Luke 22:44) and wipes it from his face with a cloth. Hardy connects the two accounts in the Narratio to a reluctance by some, including Eusebius, as expressed in his letter to Constantia, to paint images of Christ; Acts. Thad. and the Narratio get around this problem by having Jesus transfer his own image to the cloth. The stories of the image recall also Rice’s presentation on the Story of Joseph where copies made of the original, divinely-created images contain some of the supernatural power of their archetypes. I find it interesting too how the inventio traditions get highjacked to include additional stories, such as the Heliopolis tile, to provide warrant for local holy sites and relics.

Greg Given turned our attention from copies of images to copies of texts in “Re-Materializing Jesus’s Reply to Abgar: The Power of a Copy in Coptic Amulets.” Given began his interest in the Abgar Correspondence when assigned to work on a Coptic papyrus (P. PalauRib. Copt. 5; 6th/7th cent.) assigned to him while working on the Palau-Ribes collection in Barcelona. He discovered it to be an incipits amulet that includes the incipit of the Abgar letter along with the incipits of the canonical Gospels. The same combination is found in P.Lond.Copt. 317. In an article Given wrote on the Palau-Ribes papyrus, he remarked, “these papyri bear witness to a set of scriptural practices in which a sacred text’s status as ‘canonical’ or ‘apocryphal’ did not matter so much as the fact that the text worked for the ritual tasks to which it was applied” (“An Incipits Amulet featuring Jesus’s Letter to Abgar,” Journal of Coptic Studies 19 [2017]: 42–49 at 45). Given drew attention to several other artifacts of the correspondence, including a version inscribed on a door lintel from Ephesus in the 5th/6th-century (now in Vienna), 18 Coptic amulets, and a wooden plaque in Coptic. Of particular interest among these copies is a codex called P. d’Anastasi 9 (6th cent.) which has a curious expansion: “I, Jesus, I am the one who commands and I am the one who speaks…It is I, Jesus, who wrote this letter with my very own hand. The place where this handwriting will be affixed, no power of the adversary nor any unclean spirit will be able to approach not to reach into that place forever.” As customary the text begins clearly stating that it is a “copy of the letter of Jesus Christ” yet the fact that the original is said to be written in Jesus’ own hand seems to have some power. Given sought other texts that could have some bearing on this phenomenon and found the Testament of Paham, the will of a Egyptian monk. The will includes a statement that Paham wrote it in his own hand and that the text is “established and indestructible, because this is the way I have made it”—which is certainly true since it still survives today. Of course, the testament is an autograph, so declarations of writing in one’s own hand are more significant, but the motif seems important enough to be used to lend the copy of the Abgar text some power. Given also noted that Greek examples of the Abgar letters include seven seals at the end, which are found on Byzantine wills. He finished with a mention of the Epistle of Christ from Heaven, a medieval chain letter said to be written by Jesus. A copy Given showed from Oslo begins again with the statement that the text is a copy, but most interesting of all is that it includes “Jesus Christ” at the bottom of the text in the location of a signature. Anyone interested in the Abgar Correspondence may want to watch a short docudrama on the text entitled Letters of Faith. It was produced in 2007 by the Newington-Cropsey Foundation but does not seem to be available anymore. I uploaded a copy to YouTube (HERE), but watch it quickly in case it gets removed.

After lunch, our attention turned to the intersection of Christian apocrypha and pilgrimage. I presented first with “What They Took Back Home: Pilgrimage Souvenirs as Transmitters of Christian Apocrypha.” I began working on pilgrimage a few years ago when gathering sources for a paper on apocryphal Flight to Egypt traditions for a soon-to-be-published collection of essays entitled Children in the Bible and the Biblical World. The paper was twice as long as it needed to be, so some of the extra material ended up being repurposed for three Apocryphicity posts (HERE, HERE, and HERE) and some of it was included in my presentation for this conference. The presentation covered three types of pilgrim souvenirs (or eulogiai, blessings): ampullae (flasks that could contain oil, water, or dirt from the holy site), tokens (coin-like souvenirs made out of clay), and medallions/badges. The use of ampullae can be traced back to at least the time of the Piacenza Pilgrim in the sixth century, who mentions acquiring an oil flask in Jerusalem and touching it to the true cross. By the Pilgrim’s time there were holy sites all over the Mediterranean world, a number of which had no connection to canonical traditions. Presumably each sold some kind of souvenir commemorating the site; those from sites connected to noncanonical traditions, especially those that featured images related to such traditions, were vehicles for apocryphal narratives that would be carried back home, displayed in the home or work place, and served as a focus for the pilgrim to tell of their experiences. Sometimes the images on the eulogia can be tricky to identify, due largely to the desire to add pilgrims to the biblical scenes or to depict biblical characters in pilgrims’ clothing. Some images may not be biblical figures and events at all but depictions of the pilgrim, traveling by land or by sea. Some scenes, such as the crucifixion or the flight to Egypt, have clear connections to canonical sources, but they could also evoke for the bearer noncanonical versions of those same events. Undecorated artifacts are particularly problematic for tracing their origins; there could be a large number of the extant eulogiae that derive from a site with apocryphal associations, but there is no way to make that determination, just as there is no reason why it should be ruled out. The most interesting of the artifacts I shared with the participants were ampullae from the shrine of St. John in Ephesus; John’s death is narrated in the Acts of John, a text associated with the shrine in several sources including Augustine, who wrote: “And they relate of John (this is found in certain Scriptures, albeit apocryphal) that when he ordered his sepulchre to be made he was present [at the grave] alive…and that he indicates his being alive by a flow [or spring] of dust. This dust is believed to be pushed [up] by the breath of the one who sleeps there, so that it ascends from the bottom to the surface of the tomb” (In Iohannis Evangelium tractatus, PL 35, 1970–71). Other flasks from Egypt depict Saint Menas on one side and Thecla on the reverse. Also of interest is a token from a site dedicated to John the Baptist in Ein Karim, west of Jerusalem; the token features an image of Elizabeth’s and John’s flight to the mountain of refuge depicted in Prot. Jas. At the end of my presentation I noted also evidence for pilgrim sites as disseminators of copies of apocryphal texts. Late antique inventio texts, such as the ones mentioned above about the foundation of churches to the Virgin or the account of the Heliopolis tile, seem particularly suitable for such distribution, or at least for reading at the site. And I suggested that we look at our texts more closely for connections to pilgrimage, citing in particular the Arabic Infancy Gospel, which already shows hints of use as a pilgrimage map, but with its stories of miracles performed using the baby Jesus’ bath water and swaddling bands, offers hints that the stories functioned as warrants for the dissemination of flasks of water from the same bath or strips of cloth that are imitations of Jesus’ swaddling bands.

Some of the same themes from my presentation were echoed in Catherine Taylor’s (Brigham Young University) “Salvation at Hand: Annunciation Pilgrim Tokens and Material Apocrypha.” Taylor focused on representations of a canonical scene—the annunciation to Mary—that included an apocryphal element: the spinning implements mentioned in the account of the event from Prot. Jas. There is a mimetic aspect of the pilgrimage experience—to walk where Christ walked, for example, but also to re-enact episodes from the life of Christ at particular locations. Pilgrimage bridged the gap between heaven and earth, and that experience could continue for the pilgrim at home every time they came into contact with their eulogiai—particularly given that the souvenirs were believed to have powers to heal and protect. Taylor considered these qualities in relationship to the Annunciation scene, suggesting that women pilgrims could see something of themselves in the domestic image of Mary spinning, and the perceived supernatural capabilities of the Annunciation tokens may have been tied specifically to women’s experiences—such as fertility and childbirth.

The final paper of the day was delivered by Maria Evangelatou (University of California at Santa Cruz): “Between Theology and Everyday Life: Narrative Choices of Material Significance in the Protevangelion of James (2nd. c.) and in the Byzantine Kokkinnobaphos Homilaries on the Life of Mary (12th c.).” These Homilaries, based on Prot. Jas., were composed by a monk at the Kokkinnobaphos monastery named Iakobos, who was the spiritual advisor of Eirene Sebasatokratorissa, sister-in-law of emperor Manuel Komnenos and wife of Sebastokrator Andronikos. The Homilaries can be found in two richly illustrated twelfth-century manuscripts: Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 1162 (online HERE) and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, gr. 1208 (online HERE). Evangelatou began her presentation with a definition of materiality (surprisingly, the only participant to do so): “any aspect of the physical world around us that is perceived by our bodily senses. In other words, materiality is the human condition and potential of experiencing the world in and through our material bodies.” Materiality applies specifically to the Homilaries in how it is “purposefully and systematically employed in narratives of Mary’s life in order to make the mystery of God’s Incarnation through her body more understandable, relatable and memorable to a broad audience of believers.” To that end, Evangelatou presented images from the Homilaries that feature “carefully chosen narrative details of material significance that affect the day-to-day lives of the story’s protagonists: from visiting a garden and traveling to a relative’s house to performing household tasks such as drawing water from a well or spinning thread.” Each image was a visual feast and was carefully explained in light of Byzantine theology. It was a dizzying and disconcerting experience that left us all with much to think about.

Before breaking for dinner and drinks, convenor Janet Spittler took care of a little business: the formal induction of the new NASSCAL Board of Directors. Janet now takes on the duties of President, Brandon Hawk is Vice President, Eric Vanden Eykel is Communications Director, Jonathan Henry is the Student Member, and I stay on as Immediate Past President. The full list of board members can be seen on the NASSCAL web site (HERE).

Everyone who participated in the conference seemed to be in agreement that it was a great success. The variety of approaches to materiality that were applied in the presentations was broad and opened up a number of new avenues of exploration of apocryphal texts and traditions. The principles of new philology—the study of the particularities of individual manuscripts—were represented in papers by Jones, Henry, Givens, and Evangelatou, though all but Jones focused more on the texts and images within the manuscripts than the physicality of the manuscripts themselves. Jones’s interest lay in the arrangement of texts within the manuscript—specifically, asking the question of why combine these particular texts together? Several papers examined the power of physical copies: images of Jesus, such as the Hodegetria and the Mandylion, or writings by Jesus, such as the Abgar Correspondence—each so powerful that its miraculous abilities can be transferred from one copy to another. A similar transference of power is found in the pilgrimage souvenirs that convey not only physical aspects of the holy sites—such as water or pollen—back to the home of the pilgrim but also a portion of the power that derives from the manifestations of the divine that took place there. In these cases, the “material” is powerful. Many of the papers looked at images from apocryphal texts and traditions. For some of these images, the apocryphal connection is clear and unmistakable—such as the Kokkinnobaphos Homilaries or the Thecla ampullae—but others are not so certain, such as the Franks Casket or the procession depicted at the cemetery at El-Bagawat. Nevertheless, Hopkins and Laflèche demonstrated in their presentations of these images that apocryphal texts need to be brought into the discussion of their origins, even if the results are inconclusive.

The most common figure in all of the papers is the Virgin Mary. As Felicity Harley stated in her presentation, Mary is the most popular female image in Christian art of the fourth century, but of course she remained popular thereafter, and Taylor’s, Jensen’s, and Evangelatou’s presentations effectively demonstrated the widespread use of Prot. Jas. for creating these images. But sometimes the connection between the image and its source material seems more indirect—as in the Annunciation images that contain her spinning implements or the Adoration of the Magi images described by Harley that incorporate motifs that cannot be traced to any particular text. In these cases the artists may not realize that the imagery in the scenes are not part of the canonical depictions, but Evangelatou’s presentation is a reminder that even the smallest detail can have important meaning. The Digital Humanities papers may seem out of place in a conference on material objects but each of them touched on aspects of the material world that can be accessed through electronic resources: Schroeder’s Coptic Scriptorium project demonstrates the effects of colonialism on the dispersion of manuscripts, Walters made us consider how the ubiquitous, printed critical edition can take on a new form as a digital-first edition, and Hawk showed how software can plot social networks that reveal how these manuscripts were created and dispersed. A final set of papers focused on accounts of objects or places within texts. Jacob Lollar’s discussion of the History of John’s description of Ephesus leaves the mystery of why the author is so interested in the city unresolved but it is no less certain that the materiality of the city was important to the writer. The Story of Joseph of Arimathea described by Bradley Rice features a place (the church dedicated to Mary in Lydda) and an object (the image of the Virgin held within it). The object is integral for establishing the holy site and for guaranteeing its continued appeal to those who visit it.

As Christian apocrypha scholars, most of our time and energy goes into reading and, for some of us, reconstructing texts. They are the objects of our study, but the “Material of Christian Apocrypha” conference illustrated how much these texts are connected to actual objects. Any of us who have handled a manuscript or artifact, or visited a sacred place, know the power and appeal of materiality. It was no less so for ancient and medieval Christians who sought a physical connection to the traditions they valued, whether they were canonical or apocryphal.