2018 SBL Diary: Day Two

The second day of the annual meeting was significantly more relaxed. There were no Christian Apocrypha Section sessions scheduled, so I was “free” to go to anything that interested me. But before the sessions began, I attended the Journal of Biblical Literature editorial board breakfast meeting. I joined the board last year to review apocrypha-related submissions. It’s a surprisingly large group but run like clockwork by General Editor Adele Reinhartz, though she is stepping down now after many years in the role to be replaced by Mark Brett. I sat down next to Mark Goodacre (Duke University) and we talked about what we were presenting on. I began explaining my paper from day 1 by saying, “It’s an eighteenth-century manuscript containing apocryphal texts that no-one really knows anything about.” When I was finished, Mark said, “I thought you having me on for a second there.” I didn’t realize how much my description sounded like the discovery of the Secret Gospel of Mark, a text that both Mark and I are interested in but disagree completely about its authenticity (I do not believe the theory that it is a forgery, created by its discoverer, Morton Smith; Mark refuses to see reason).

After breakfast, I hustled over to the Metacriticism of Biblical Scholarship session, which focused on the Museum of the Bible. I have been following the steady stream of criticism about the museum that began even before it opened, and enjoyed Candida Moss’s and Joel Baden’s investigation of it in their book Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby (Princeton, 2017). As it happens, I ran into a scholar who works for the museum on day 1. He was complaining that no one from the museum was asked to be on the panel or to respond to the papers; he also minimized the central argument in the session that the museum exhibits are infused with an Evangelical narrative. He seemed to be saying that there was “nothing to see here.” Well, two and a half hours of presentations and discussion proved otherwise. I won’t go into the details of each presentation, but it was clear that the museum had a very Christian agenda, at times minimizing problematic portions of the text (e.g., using the King James Version to translate doulos in Ephesians as “servants” rather than “slaves” and stating that some passages in the Bible “seem to endorse” slavery) and at other times essentially writing Judaism out of the Bible (everything leads up to Jesus). The participants in the session were divided over whether the museum could change its approach and be “redeemed” or should “own what it is” and label itself the Evangelical Biblical Museum (as Jill Hicks-Keeton [University of Oklahoma] said, you cannot do a walkthrough of the Bible that is both Jewish and Christian). Concerns were raised too about how to treat students who are enticed by grants to work with the museum—it seems unfair to blacklist them given that they may be doing so out of financial desperation; and about the difficulties faced by text critics who do not want to work with the museum (because of their appalling history of purchasing unprovenanced artifacts, some of which have been proven to be fakes) but feel they need to in order to get access to the museum’s storehouse of manuscripts. The most emotional reaction to the museum came from audience member Mark Leuchter (Temple University) who said he was “tired of being civil” about the museum and its anti-semitism. He does not believe they will change and thinks that they don’t want to. I suspect he is right, and my earlier conversation with the scholar from the museum indicates to me that they don’t see what they do as problematic. I have to wonder, though, about the scholars who work with the museum who are not from an Evangelical background. Why do they do it? Are they the equivalent of the mythical members of Trump’s White House who work in the administration, it is claimed, in order to minimize the damage? In both cases, participation just validates the institution and does more harm than good. If you want to follow the continuing conversation about the session, check out the Twitter feeds of Hicks-Keaton and Cavan Concannon (University of Southern California).

After breakfast, I hustled over to the Metacriticism of Biblical Scholarship session, which focused on the Museum of the Bible. I have been following the steady stream of criticism about the museum that began even before it opened, and enjoyed Candida Moss’s and Joel Baden’s investigation of it in their book Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby (Princeton, 2017). As it happens, I ran into a scholar who works for the museum on day 1. He was complaining that no one from the museum was asked to be on the panel or to respond to the papers; he also minimized the central argument in the session that the museum exhibits are infused with an Evangelical narrative. He seemed to be saying that there was “nothing to see here.” Well, two and a half hours of presentations and discussion proved otherwise. I won’t go into the details of each presentation, but it was clear that the museum had a very Christian agenda, at times minimizing problematic portions of the text (e.g., using the King James Version to translate doulos in Ephesians as “servants” rather than “slaves” and stating that some passages in the Bible “seem to endorse” slavery) and at other times essentially writing Judaism out of the Bible (everything leads up to Jesus). The participants in the session were divided over whether the museum could change its approach and be “redeemed” or should “own what it is” and label itself the Evangelical Biblical Museum (as Jill Hicks-Keeton [University of Oklahoma] said, you cannot do a walkthrough of the Bible that is both Jewish and Christian). Concerns were raised too about how to treat students who are enticed by grants to work with the museum—it seems unfair to blacklist them given that they may be doing so out of financial desperation; and about the difficulties faced by text critics who do not want to work with the museum (because of their appalling history of purchasing unprovenanced artifacts, some of which have been proven to be fakes) but feel they need to in order to get access to the museum’s storehouse of manuscripts. The most emotional reaction to the museum came from audience member Mark Leuchter (Temple University) who said he was “tired of being civil” about the museum and its anti-semitism. He does not believe they will change and thinks that they don’t want to. I suspect he is right, and my earlier conversation with the scholar from the museum indicates to me that they don’t see what they do as problematic. I have to wonder, though, about the scholars who work with the museum who are not from an Evangelical background. Why do they do it? Are they the equivalent of the mythical members of Trump’s White House who work in the administration, it is claimed, in order to minimize the damage? In both cases, participation just validates the institution and does more harm than good. If you want to follow the continuing conversation about the session, check out the Twitter feeds of Hicks-Keaton and Cavan Concannon (University of Southern California).

Before the afternoon sessions, I sat down for a tea/coffee with James (Jamey) Walters, who presented in the first Christian apocrypha session from day 1 on one of the texts he has translated for MNTA 2, the Exhortation of Peter. I’ve worked with Jamey for a number of years now, beginning with my article (co-written with Slavomir Ceplo) for the journal Hugoye on the Legend of the Thirty Pieces of Silver, which he guided through the publication process. But in all that time, Jamey and I have never met, so this was a good opportunity to have a chat, much of which was about comicbooks. I then had a short meeting with my editor at Yale University Press who wanted to check in with me on my progress on the Introduction to Christian Apocrypha I am supposed to be working on for the Anchor Bible Reference Library (I promised to start work on it real soon).

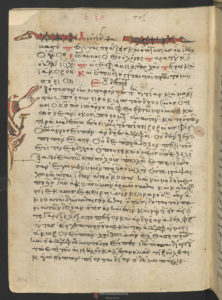

And my choice for the last session of the day was Book History and Biblical Literatures. The theme of the panel was “New (Material) Philology and Textual Objects.” Each of the presenters were given 12 minutes to discuss a particular physical copy of a text. I was most interested in the two presentations by MNTA 2 contributors Adam Bremer-McCollum (University of Notre Dame) and Janet Spittler (University of Virginia). Bremer-McCollum’s paper, “Two Languages, Two Scripts, and Three Combinations Thereof: A Personal Prayer-Book in Syriac and Old Uyghur from Turfan,” was essentially descriptive, and perhaps out of most of the session participant’s comfort zone (Old Uyghur? What the hell is that?). But Spittler’s paper, “The Acts of John 87–105 (Vienna hist. Gr. 63 fol. 51v–55v): Is it a ‘Fragment?’”, dealt with a fundamental issue in the reconstruction of the apocryphal acts (that’s in my comfort zone!). The Acts of John is no longer complete and has to be reconstructed from portions of the text preserved in a variety of manuscripts. The Vienna manuscript was published by M. R. James in 1897, at which time he described the text as a “fragment” of the original Acts of John. But Spittler demonstrated from images of the manuscript, that it is not a “fragment” at all, but a self-contained narrative that goes by the title (in James’s translation) “A wonderful narrative concerning the acts and visions, which Saint John the Divine saw at the hand of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Since James’s time, we have come across several self-contained stories about apostles (such as the Act of Peter from the Berlin Codex, or the Act of Peter in Ashdod) that likely are not excerpts from larger apocryphal acts after all. Modern scholars of apocrypha are less in a rush than our predecessors to connect the texts we discover to the testimony about such texts from early and late antique church writers. Spittler’s presentation was a helpful reminder of that fact and a lesson about the need for us to re-examine the manuscripts used by previous scholars.

The session ended with an interesting “bonus.” A member of our band of apocrypha scholars stopped at one of Denver’s dispensaries and brought back an edible to share. This person, who I will refer to only as “Pusha B,” convinced a few of us who have never used cannabis in our lives (we are so plain-white-toast) to give it a try. We were not the only biblical-scholars-behaving-badly—I saw many SBL attendees sheepishly popping into dispensaries over the weekend (and I have a confused email from one colleague on my phone that reads “It’s possible I’m a little high”). Infused with the “devil’s lettuce,” I headed off to dinner with a group of fellow University of Toronto alumni, followed by further elbow-rubbing with Canadians at the U of T reception. Believing that my one bite of canna-chocolate was having no effect, I asked Pusha B for a little more and then my memory of the night gets a little fuzzy. All I remember is babbling to my roomie in an increasingly slurred voice and nodding off to sleep.

The session ended with an interesting “bonus.” A member of our band of apocrypha scholars stopped at one of Denver’s dispensaries and brought back an edible to share. This person, who I will refer to only as “Pusha B,” convinced a few of us who have never used cannabis in our lives (we are so plain-white-toast) to give it a try. We were not the only biblical-scholars-behaving-badly—I saw many SBL attendees sheepishly popping into dispensaries over the weekend (and I have a confused email from one colleague on my phone that reads “It’s possible I’m a little high”). Infused with the “devil’s lettuce,” I headed off to dinner with a group of fellow University of Toronto alumni, followed by further elbow-rubbing with Canadians at the U of T reception. Believing that my one bite of canna-chocolate was having no effect, I asked Pusha B for a little more and then my memory of the night gets a little fuzzy. All I remember is babbling to my roomie in an increasingly slurred voice and nodding off to sleep.