2018 SBL Diary: Day One

Another year, another SBL Annual Meeting. And now it’s time to compile my thoughts about the experience for my traditional roundup of the event—the sessions I attended and/or participated in, meetings I had with scholars and publishers, books I purchased, and receptions I crashed. I do this for those interested in Christian apocrypha who could not attend the meeting and also in lieu of tweets because Wi-fi access tends to be somewhat spotty (and generally a pain to do while trying to listen to papers).

Travel is always part of the experience. For me, the process of getting to Denver began on Friday at 8am with the drive to Pearson airport in Toronto for a noon flight. The previous day had made travel on the roads very difficult. I went to a concert (The Alarm, a kinda Welsh version of U2) in the city and the drive took four hours (it should have been 1.5). I mention the concert also because it damaged my hearing, so I really had to struggle to hear anything for the first few days of the conference. I need not have worried about getting to the airport on time; all was clear Friday morning, so I had a smooth, uneventful drive. Not everyone was so lucky; friends of mine from Sudbury and London had an extra day of travel due to delays in connecting flights. The only wrinkle for me was a 2.5 hour stopover in Detroit. Every time I book flights I pick the cheap option, then once I’m in transit, I curse myself for having been so frugal. The plane arrived in Denver slightly early at 5pm and I waited for my conference wife Bradley Rice (McGill University) to arrive. And waited. And waited. Not only was his plane a little late but they managed to lose his luggage too. Our plan was to meet up with Eric Vanden Eykel (Ferrum College) and Rick Brannan (Faithlife) for food and drinks. Though two hours late, we managed to spend some time with them and headed to the hotel around 10pm. By this time the double queen room we booked had been given to someone else, so they put us in a single king room with a rollaway bed on the 36th floor. As consolation we were given access to a lounge with free breakfast and snacks. Sweet.

The first real day of the conference began Saturday morning with the first session of Christian apocrypha, grouped around the theme “New and Neglected Christian Apocryphal Texts.” One of our presenters, Florentina Badalanova Geller (Freie Universität Berlin), did not arrive, so we ended up with the dreaded all-male panel. To fill in the time, chair Tobias Nicklas (Universität Regensburg) asked me to say a few words on the forthcoming second volume of More New Testament Apocrypha. I’m not real good at improvising and found that the jet lag and altitude sickness (I decided to blame every faux pas of the weekend on altitude sickness) had robbed me of all cognitive function—I couldn’t remember any of the texts in it! Thankfully some whispered cues from Janet Spittler (University of Virginia) got me through. Tobias spoke also on his DFG (German Research Foundation) funded project “Beyond the Canon: Heterotopias of Religious Authority in Late Antique Christianity” (details HERE). One of the first initiatives of the project is a conference in Regensburg in Summer 2019 in which I have been asked to participate.

As for the papers in our session, two of them were about texts that will be in MNTA 2 (and could I remember that during my improv moment? Altitude sickness). The first of these was Chance Bonar (Yale University) on “An Introduction to 3 Apocryphal Apocalypse of John.” I have already said too much about this text in previous posts (HERE, HERE and HERE), so I won’t say more now except that I think Chance is a young scholar to watch out for. He was a pleasure to work with on this text. The second MNTA paper was by James Walters (Rochester College): “The (Syriac) Exhortation of Peter: A New Addition to the Petrine Apocryphal Tradition.” The text is one of three Syriac Petrine texts that James is contributing to the volume. Not long after Walters submitted his work on the text, another scholar (Sergey Minov) published an edition and translation of it. Fortunately, all was not lost. Walters presented an argument for why his translation offers something of value to the study of the text. Minov used two manuscripts: one with a single episode in which Peter delivers a parable about vigilance, and the second with an additional episode about a solitary who undergoes temptation from Satan. Minov believes the story of the solitary is an entirely separate text and decided not to include it in his edition. Walters showed us that the two stories do seem to be belong to a single text, even if only in a secondary expansion of a shorter original. Walters has made the Syriac text of the Exhortation to Peter available on the Digital Syriac Corpus (HERE), a project that I hope to contribute to in the near future. Also featured in the session was Bradley Rice’s exploration of “The Suspension of Time in the Book of the Nativity of the Savior.” Brad is working on traditions about Jesus as the Star of Bethlehem, a motif given prominence in the Revelation of the Magi but found also in Birth Sav.—an early infancy gospel that exists today combined with the Protevangelium of James to form the J Composition. The suspension of time occurs in Prot. Jas. 18; here Joseph has left Mary in a cave to go in search of a midwife and he tells, in first-person narration, of the animals and humans stopping in their tracks, and the stars and clouds standing still. The episode stands out in the text, leading some scholars to see it as a later addition. A similar episode occurs in Birth Sav. but the experience is assigned to the midwife, who helps Mary deliver in a house, not a cave, and there witnesses all sound and movement stop and then the Christ child appears in the form of a bright light. Brad thinks Birth Sav.’s version of the suspension of time to be more original—reasoning that it is more likely to have been transferred from the midwife to Joseph rather than the reverse. Furthermore, he argued that it makes better sense in Birth Sav.’s context, where everything stops as Jesus, as a star, descends from the heavens to the midwife’s home.

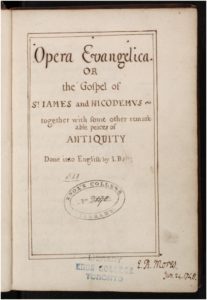

The only remaining paper in the session was delivered by me and Greg Fewster (University of Toronto) under the provocative title “Opera Evangelica: The Discovery of a Lost Collection of Christian Apocrypha.” Greg and I ran into each other at the 2017 SBL and discovered we had both independently come across the Opera Evangelica at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto. The text is a collection of apocrypha in English translation created in the early 18th century, before the first published English translation by Jeremiah Jones in 1726. We came across a second copy in Cambridge University and our paper described the contents of the collection, the differences between the two copies, and our theories of origin for each of them (the Toronto copy is attributed to “I. B.” and Cambridge is anonymous; both were created before 1715, the date when the Cambridge copy was donated to the library). It’s a peculiar artifact. The secrecy of it—copied by hand and circulated, it seems, among a small group—suggests that its creator may have felt that showing an interest in apocryphal texts could be damaging to their career, particularly given that the author/editor has a rather positive perspective on the value of the texts.

The only remaining paper in the session was delivered by me and Greg Fewster (University of Toronto) under the provocative title “Opera Evangelica: The Discovery of a Lost Collection of Christian Apocrypha.” Greg and I ran into each other at the 2017 SBL and discovered we had both independently come across the Opera Evangelica at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto. The text is a collection of apocrypha in English translation created in the early 18th century, before the first published English translation by Jeremiah Jones in 1726. We came across a second copy in Cambridge University and our paper described the contents of the collection, the differences between the two copies, and our theories of origin for each of them (the Toronto copy is attributed to “I. B.” and Cambridge is anonymous; both were created before 1715, the date when the Cambridge copy was donated to the library). It’s a peculiar artifact. The secrecy of it—copied by hand and circulated, it seems, among a small group—suggests that its creator may have felt that showing an interest in apocryphal texts could be damaging to their career, particularly given that the author/editor has a rather positive perspective on the value of the texts.

The session segued into the Christian Apocrypha Section business meeting. We solicited some suggestions for next year’s sessions from the audience and then the steering committee worked to arrange the suggestions into our usual number of four sessions. These have yet to be fine-tuned but at present we are looking at a session on the material of apocrypha (as a sequel of sorts to the NASSCAL conference taking place at the University of Virginia next week; details HERE) and a panel about constructing critical editions. We also selected new chairs for the section: Janet Spittler and Lily Vuong. Our appreciation goes out to Brent Landau for steering our ship for the past three years (and the three years before that as co-chair with me).

For lunch I met up with Chris Frilingos (Michigan State University), author of the recent monograph Jesus, Mary, and Joseph: Family Trouble in the Infancy Gospels (University of Pennsylvania Press). We share an interest in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas but after all these years of working in parallel, we had never actually met in person. So this lunch meeting remedied that and Chris was good company. One thing about our conversation that particularly struck me was Chris’s statement that my work on the gospel changed scholars’ perceptions of the text—people stopped simply making fun of it and started to take it more seriously. My work made Chris’s (and others’) work possible, he said. Not a bad legacy, I guess. After lunch, it was time to check out the book display. In previous years I have posted on books to look for at SBL but there was not a lot to offer this year on Christian apocrypha. Nevertheless, I picked up a few titles: Sean McDowell, The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus (Routledge), Edmond L. Gallagher and John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity (Oxford), Joan E. Taylor, What Did Jesus Look Like? (T. & T. Clark), Stephen Shoemaker, Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion (Yale), and Karl van der Toorn et al., Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (not specifically apocrypha-related but a steal at $25 from Brill).

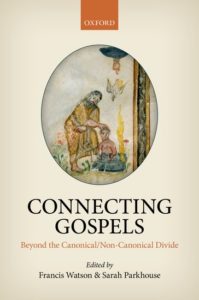

The second apocrypha session of the day, “Connecting Gospels,” grew out of a project on comparing the treatment of characters, themes, and motifs across canonical and non-canonical texts. The fruits of that project were published just a few months ago in Francis Watson and Sarah Parkhouse (eds.), Connecting Gospels: Beyond the Canonical/Noncanonical Divide (Oxford). Watson (University of Durham) joined the panel for “‘Inasmuch as Many Have Attempted…’: The Apocryphon of James and the Problem of Gospel Plurality.” He took the Gospel of Matthew and other orthodox traditions with their view that all the apostles were sent out on mission and (according to Irenaeus) they all wrote gospels (though I don’t think Irenaeus meant all preached AND all wrote) and juxtaposed them with Apoc. Jas. with its declaration that while the other apostles wrote their gospels, James and Peter are given a message dictated by Jesus that the two are to keep secret. Watson noted that the Apoc. Jas. is not particularly unorthodox, and asked why does it contain such hostility toward the canonical Gospels and the other apostles? He argued that it was due to elevating revelation in the present over experience in the past. In her response to Watson, Julia Snyder (Universität Regensburg) the respondent to the entire session, suggested that Apoc. Jas. is not entirely hostile to other gospels and urged Watson to consider the “secrecy” of the text as a way of marketing it to second-century readers as something new and noteworthy.

The second apocrypha session of the day, “Connecting Gospels,” grew out of a project on comparing the treatment of characters, themes, and motifs across canonical and non-canonical texts. The fruits of that project were published just a few months ago in Francis Watson and Sarah Parkhouse (eds.), Connecting Gospels: Beyond the Canonical/Noncanonical Divide (Oxford). Watson (University of Durham) joined the panel for “‘Inasmuch as Many Have Attempted…’: The Apocryphon of James and the Problem of Gospel Plurality.” He took the Gospel of Matthew and other orthodox traditions with their view that all the apostles were sent out on mission and (according to Irenaeus) they all wrote gospels (though I don’t think Irenaeus meant all preached AND all wrote) and juxtaposed them with Apoc. Jas. with its declaration that while the other apostles wrote their gospels, James and Peter are given a message dictated by Jesus that the two are to keep secret. Watson noted that the Apoc. Jas. is not particularly unorthodox, and asked why does it contain such hostility toward the canonical Gospels and the other apostles? He argued that it was due to elevating revelation in the present over experience in the past. In her response to Watson, Julia Snyder (Universität Regensburg) the respondent to the entire session, suggested that Apoc. Jas. is not entirely hostile to other gospels and urged Watson to consider the “secrecy” of the text as a way of marketing it to second-century readers as something new and noteworthy.

Tobias Nicklas’s paper, “Water into Beer! Transformations of Biblical Miracles in Late Antique and Early Medieval Traditions,” began with an amusing story from the Life of Saint Brigid in which she transforms water into beer for some thirsty lepers—she didn’t heal the lepers, she just satisfied their thirst. Nicklas sees this and other tales (such as the bringing of Jesus’ image to Edessa in the Doctrine of Addai or the establishment of the holy fountain in Matarea in the Arabic Infancy Gospel ch. 24) as efforts to establish Christianity in areas far from the land of Jesus’ ministry. Such transfer of miraculous abilities to other figures is not so removed from canonical texts, Snyder responded, noting the various miracles performed by the apostles in the book of Acts. She also connected the repetition of certain well-known miracles stories (such as the transformation of water into another—better!—liquid) to a desire of the writers to give their readers something familiar and comforting (Snyder compared this to television crime shows that essentially tell the same story over and over again). Yet another text from MNTA 2 was the focus of Janet Spittler’s paper, “The Minor Acts of Thomas and John 20:24–29.” The text, which Spittler and her student Jonathan Holste, with whom she worked on it, prefer to call the Acts of Thomas and His Wonderworking Skin, features an episode in which Thomas is tortured and in calling out to Jesus for help, recalls his moment of doubt in John 20. Spittler asked the audience for other examples of biblical figures crying out in pain (to which Snyder offered Jesus on the cross and in the garden, Job, and others; she also suggested looking for examples of human suffering in general). There was some discussion also of possible connections between the text and relics—did some church somewhere claim to have a piece of Thomas’s wonderworking skin? I suspect so and I think this text would work perfectly as a supporting document for such claims. The only problem with this view, as Spittler pointed out, is that Thomas gets his skin back at the end of the text and then flies off on a cloud to meet the apostles in Jerusalem. Nevertheless, this does not preclude that, once deceased, his skin could be used as a relic.

Finally, fellow Canadian (even better, fellow English ex-patriot and Canadian) and (yet another) fellow Infancy Gospel of Thomas enthusiast Rob Cousland (University of British Columbia) presented on “Rereading the Christology of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas: The Rewriting of Luke 2:41-52 in Paidika 17.” Cousland recently published an excellent monograph on the text: Holy Terror: Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas (Bloomsbury). His SBL paper looked specifically at several elements Infancy Thomas adds to the story of Jesus in the Temple: Luke’s “teachers” become “teachers and elders” and instead of merely listening to them and asking them questions, Thomas’s Jesus “explained the main points of the law and the riddles and the parables of the prophets.” Cousland takes from this that Infancy Thomas is embracing aspects of Judaism (the full range of Jewish Scripture, essentially) rejected by other Christian groups. Furthermore, Jesus’ explanations here would naturally be about how he is reflected in Jewish Scripture, as the adult Jesus explains to the disciples on the road to Emmaus in Luke (see esp. 24:44–47). A potential problem with Cousland’s argument is the amount of variation in the manuscripts of Infancy Thomas at this point, though most witnesses have at least the combination of law and prophets. Snyder mentioned in her response also that the Jewish teachers in the text may be intended as straw men for intra-Christian conflict more than a reflection of dialogue between Jews and Christians.

After the final session, Brad and I searched for somewhere to eat, which was no small feat because another 8000 or so people were trying to find a restaurant table at the same time. We finally made it back to the hotel for 9 pm and decided to skip the receptions and call it a day. It was really gratifying to see so many papers focusing on texts from MNTA 2; there is nothing more exciting for Christian apocrypha scholars than to hear about new texts. And I am always happy to talk to people working on Infancy Thomas. Day one was pretty intense (and judging from the length of this post, rewarding). Could days two and three top this? Stay tuned.