Christian Apocrypha and Pilgrimage, Part 2

The earliest Christian pilgrimage itineraries, discussed in the part 1 of this series post, say little about sites in Egypt, despite the fact that the canonical Gospel of Matthew (2:13–15, 19–21) narrates a visit to Egypt by the Holy Family early in Jesus’ life. Matthew does not say what happened to the Holy Family in Egypt nor how long they resided there, but other Christian writers filled the gap with tales of the family visiting various locations in Egypt, each one a site of miraculous proofs of Jesus’ divinity and superiority over native deities. As time went on, these flight narratives became more and more elaborate, with the most detailed accounts serving as pilgrimage maps for those who want to follow Jesus’ footsteps and visit the sites where Jesus performed his wonders, either in person or vicariously through reading the texts.

The apocryphal flight narratives range in origin from East to West and from roughly the fifth to eighth centuries, with further expansion in the manuscript tradition and in other literature inspired by these tales for centuries thereafter. The earliest developed narrative of the flight story is likely the tales collected in the Gospel of the Infancy, extant today in Syriac and Arabic (for more information visit the e-Clavis pages for the Arabic Infancy Gospel and the East Syriac History of the Virgin). The flight narrative comprises the middle portion of this text (corresponding to Arab. Gos. Inf. 10–24). The section begins with a retelling of Matthew 2:13–15 (Arab. Gos. Inf. 9), and then, within a day’s journey, the family arrives in the first of several unnamed Egyptian cities (10–12). The city is host to an idol to whom the other idols and divinities in Egypt are subservient. The family enters the city’s hospital, which is dedicated to the idol, and the earth trembles, causing all of the idols to fall. The story, a literal interpretation of Isaiah 19:1 (“See, the Lord is riding on a swift cloud and comes to Egypt; the idols of Egypt will tremble at his presence, and the heart of the Egyptians will melt within them”), is designed to show the superiority of Jesus to other gods and to foreshadow the conversion of pagan lands to Christianity. The remaining stories have a much different tone. The family moves from city to city, but not in flight—that is, they are not pursued by Herod’s soldiers, though they are exiles, wandering the desert without home. In each town they encounter rulers and nobles, perform healings, and are suitably honored and given provisions before they move to the next.

Another apocryphal flight narrative that circulated in the East is found in the Armenian Infancy Gospel, which also seems to have an origin in, or at least through, Syriac. After a retelling of Prot. Jas. (chs. 1–14), the narrative shifts to the family’s exile (ch. 15). They move first to Ashkelon, then Hebron, and then to Egypt to escape the soldiers of Herod. For the first time, names are given to the cities visited by the family, along with precise times they spent there. “At the many stations where they lodged,” the text reports, “the child Jesus would draw water out of the sand and would offer it to them to drink” (15.3). The water is necessary for their survival but the author is laying the groundwork here for pilgrimage to sites boasting to be the location of a healing spring or a sacred well. The family arrive in Egypt at the plains of Tanis, where they stay for six months, before moving on to Cairo, where they stay for two years and four months (15.4). Then they move to another, unnamed city with high walls decorated with statues of beasts, all of whom fall when Jesus enters the city (15.6–7). They stay there for a year. The city also has a massive temple of Apollo, and during his festival, Jesus, upset at the worship of this “false” god, causes the temple to fall, killing all of the priests (15–16). The family are later invited to live with a Hebrew prince named Eleazar, who is father to Lazarus, Mary, and Martha, and who had brought his family to Egypt because of persecution by Herod (23–25). The family stays with him for three months (26) before being summoned home by the angel; along the way they camp at Mount Sinai (28). Many of the themes observed in Arab. Gos. Inf. are found also in the Armenian text. The family is continually on the move, sometimes because of the trouble they stir up in the city, but mostly to continue their exilic wandering; along the way temples are destroyed and healings performed in order to demonstrate Jesus’ superiority over other gods.

Christians in the West encountered the flight narrative in a Latin expansion of the Protevangelium of James known today as the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew. At ch. 17 the angel tells Joseph to flee to Egypt and then follows a series of stories told on their journey (18–24). In the first story (18–19), the family stop at a cave to cool off. Three boys and one girl accompany them, but no mention of this larger company is made hereafter, and they may be present here only to provide a contrast to Jesus, who remains calm when a dragon comes out of the cave, whereas the boys run away in fear. The dragons worship Jesus, an event said to have happened in fulfillment of Psalm 148:7 (“Praise the Lord from the earth, dragons and all the depths”). The travelers journey on and additional animals—lions, panthers, and other wild beasts—worship and accompany them, thus fulfilling Isaiah 65:25: “The wolf and lamb will feed together, and the lion and the ox will feed on straw together.”

In the next story (20–21), Mary is fatigued and rests beneath a palm tree. Jesus sits in her lap and calls out to the tree to bend down and provide fruit for his mother. He then commands water to spring up from its roots and refresh the family. Jesus rewards the tree by commanding an angel to take one of its branches and plant it in Paradise. The legend bears some similarity to a tale of Jesus in Egypt from the History of the Church of Sozomen (ca. 439–450). He reports a story of a tree in Hermopolis called Persis, which was given healing powers by Jesus as a reward for bending down and worshiping him, an event, once again, linked to Isaiah 19:1 (Hist. eccl. 5.21.8–11). This connection between the tree and Isaiah 19:1 is significant, as the same passage is cited in the next story in Ps.-Mt. (22–24). Here the family finally arrive in Egypt, thanks to Jesus shortening a journey of 30 days into one (cf. Arab. Gos. Inf. 9). They come to a town named variously in the manuscripts—Sohennen, Syenem, Shohen, etc.—and difficult to identify, though some manuscripts say it is near Hermopolis. There they enter a temple housing 365 idols and the idols fall, thus fulfilling Isaiah 19:1.

Additional tales of the family’s time in Egypt are featured in an expanded version of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas assigned the designation Greek D and known also in a Latin translation. The expansion entails a brief prologue that appears designed to connect Inf. Gos. Thom. with Prot. Jas.—the title attributes the text to “James, the brother of God” and concludes with a reproduction of the final verse of Prot. Jas. It begins with a reproduction of Matt 2:13 and adds the detail that Jesus was two years old when he went to Egypt. Little is said about the journey to Egypt, except for one brief episode: “As they were passing through the grainfields, he began to pluck the heads of grain and eat them” (2). The story is longer in some of the Latin witnesses—one version presents it as an etiology for an unnamed field that “each year that it is to be sown, it returns as many measures of grain to its owner as many seeds as it accepted from him.” The story may have some connection to the Field of the Lord in Jericho mentioned in the itineraries of the Piacenza Pilgrim and Theodosius. Once Mary and Jesus reach Egypt, they stay in the house of an unnamed widow, but after a year, the widow drives them out of her house after Jesus performs a miracle in which he makes a salted fish come to life (3–4). A similar structure is at play in the final story of the prologue, in which Jesus and Mary encounter a teacher, who chases them out of the city after the young Jesus foretells an event that comes true (5–7). The prologue comes to a close when the angel of the Lord comes to Mary and tells her to return home (as in Matt 2:19–21). This Egyptian prologue is relatively neglected in scholarship, since it appears in a late branch of the Inf. Gos. Thom. tradition, one that cannot be traced earlier than the twelfth century. Still, it has some noteworthy elements—including the theme of constant flight that is present, but not as prevalent, in the other Egyptian narratives; the Holy Family is forever on the move, chased from one city to another.

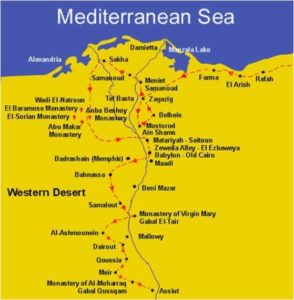

The Flight to Egypt is transformed from an exile story to a full-blown pilgrimage map in the final text in this survey: the Vision of Theophilus. The text is little-known in the West, even to Christian apocrypha scholars, but it is highly important in Coptic Christianity as one of several efforts by the late antique Egyptian church to establish Egypt as a new Holy Land with pilgrimage sites on par with those of Palestine. Today there are some forty sites on the official pilgrimage map of the Coptic Church, some established only a few decades ago, and other sites known only in oral tales are situated in-between. The flight is such an integral part of the identity of Coptic Christianity that some elements of the narrative frequently appear in iconography—showing the mother and child on a donkey and Joseph walking alongside, or the family in a boat on the Nile—and of the six pilgrimage festivals dedicated to Mary, five are held at sites associated with their sojourn in Egypt.

Vis. Theo. belongs to a genre of texts that feature an apocryphon framed by a homily delivered on a feast day dedicated to the subject of the embedded text; this genre was popular in Egyptian Christianity of the fifth century and was employed to establish festivals and encourage the veneration of saints and angels. In Vis. Theo. the flight to Egypt is narrated by Mary, who appears to Theophilus, the patriarch of Alexandria (r. 385–412), while he was staying at a house on the grounds of Dayr al-Muharraq, a monastery on a holy mountain near the village of Qusqam. The house is said to have been the dwelling of the holy family for six months of their three-year and six-month stay in Egypt. Theophilus gives the details of his vision on the feast day of Mary’s dormition.

In its earliest extant form, Vis. Theo. features three stories associated with explicitly named sites in Egypt: Tell Basta, al-Ashmunayn, and Qusqam. Tell Basta is celebrated as the first town visited by the Holy Family in a retelling of the story of the fallen idols and the thieves from Arab. Gos. Inf. 10–13 (pp. 19–21). The author’s choice of Tell Basta as the location for the story is not accidental. In antiquity it was a thriving and powerful city known for being a center for the worship of Bastet, the cat goddess. The city was prominent enough for it to earn Ezekiel’s rebuke (30:17) and Herodotus (2.58–60) documents a festival there for Bastet that drew 700,000 pilgrims. Tell Basta remained an important city into Christian times. Early pilgrims who followed the footsteps of the Holy Family could associate its Christian transformation to Jesus’ visit and when the city went into decline in the seventh century, they could pass by the ruins and attribute its demise to Jesus’ curse on the town and the destruction of its temples.

From Tell Basta the family moves on to the second major site: the village of al-Ashmunayn, known in antiquity as Hermopolis, the location of the healing tree mentioned by Sozomen. Vis. Theo. also mentions the tree, though here it is named Mukantah. Jesus also encounters statues of horses at the gate of the city, which crumble at his presence, and five camels that block the family’s path are turned to stone—presumably these two groups of statues were still extant when the author wrote the text. When the family enter the city, once again all the idols of the town fall to the ground (pp. 21–23).

After a brief stop in Qenis, the family reach Qusqam, home to the monastery of Dayr al-Muharraq. On their climb up the mountain, Jesus creates two sacred sites: he plants Joseph’s staff and from it comes an olive-bearing tree, and he creates a healing spring from Mary’s tears. Once they find shelter at the house that will one day become a church, they are visited by a friend of Joseph named Moses (Yusa in the Arabic versions) who dies after warning the family of the approach of Herod’s soldiers. The remains of Moses are said to reside in the wall of the church there to this day (pp. 30–35); they seem to have been lost for some time, however, until their rediscovery (or so it is claimed) during renovations in the monastery in 2000.

After six months, an angel comes to tell Joseph that Herod has died and the family may return home (p. 35). Before they leave, Jesus consecrates the house and says it will become a church and that pilgrims who come there will be blessed, their sins forgiven, their infirmities healed, and all of their requests answered; barren women will give birth to sons and monks will live there in protection (pp. 35–36). The family return to al-Ashmunayn and head home on a ship that Jesus creates by making the sign of the cross on the water (p. 37). Mary concludes her vision by telling Theophilus about a gathering after Jesus’ death at the house of Mary, the mother of John Mark. The apostles are present, along with Mary Magdalene, Anna, and Salome. She recounts her various trials (evoking, it seems, the similar event in the Dormition of the Virgin). And then Jesus appears and takes them all in a cloud to the house at Dayr al-Muharraq which they consecrate as the first church in all the world and then return to Jerusalem (pp. 37–39). The vision ends with Mary telling Theophilus to write everything down so that the world knows about the history and miraculous qualities of the house (pp. 39–40).

The account of the family’s journey in Vis. Theo. grew over the centuries, both in the text’s manuscript tradition and in other texts that expanded on Vis. Theo.’s itinerary. The additional tales usually include sacred wells and signs of the family’s presence, such as the imprint of Jesus’ foot in a stone; in some tellings the family is continually pursued by Herod’s soldiers, providing a greater impetus for their continual movement from one town, one pilgrimage site, to another. The creation of these stories also influenced manuscripts of Arab. Gos. Inf.; in the version edited by Heinrich Syke there is a tale inserted in which Jesus visits the town of Matariya,where there is a sacred sycamore tree that grew from where Jesus’ sweat hit the ground and a spring that Jesus produced so Mary could wash his garments (ch. 24 in Sike’s numbering). The family then moves on to Memphis where they stay three years (ch. 25).

Despite the great distance that separates the Eastern and Western traditions there is a surprising amount of commonality between them. The application of Isaiah 19:1 to the fall of the Egyptian idols and the palm tree miracle seem to be integral to the flight tradition, and other elements weave in and out of the sources, such as the presence of the thieves and the creation of springs. Themes also recur: constant movement brought on by pursuit by Herod’s soldiers or the abuse of the townspeople, the Christianization of pagan holy sites, and the portrayal of Jesus as a god wandering among people. All of the texts attempt to satisfy a desire common throughout Christendom for more information about where Jesus went and as the traditions develop, an increasing interest in how one might also journey there.